Did Martin Luther King predict his own death?

Getty Images

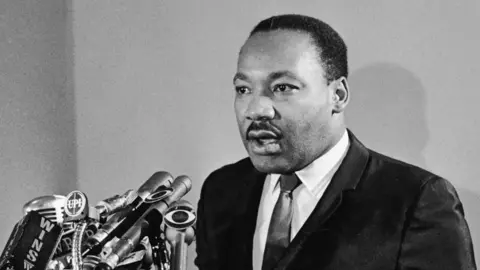

Getty ImagesFifty years ago, Martin Luther King gave his final speech. Did he conclude by predicting his assassination?

It was a bin lorry that brought Martin Luther King to Memphis the week he was killed.

Two months earlier, two black bin-men - Echol Cole and Robert Walker - took shelter in their lorry during a storm.

When a switch malfunctioned, they were crushed. Their deaths, the city's response, and the workers' conditions, led to a strike by hundreds of black employees.

So, when Martin Luther King stood in front of 2,000 people at the Mason Temple, on a stormy April night in Memphis, it was to support Cole, and Walker, and the colleagues they left behind.

What came next, though, meant it was remembered for much more.

Really, the speech was not about the strike - it wasn't mentioned until 11 minutes in - but the struggle, and Dr King's role in it. The final passage looks like prophecy.

"We've got some difficult days ahead," Dr King told the crowd. "But it really doesn't matter to me now, because I've been to the mountain top, and I don't mind.

"Like anybody, I would like to live a long life - longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now.

"I just want to do God's will. And he's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over and I've seen the Promised Land.

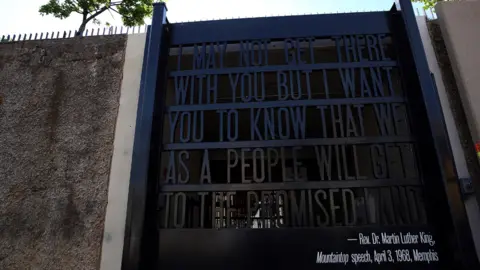

"I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.

"And so I'm happy tonight; I'm not worried about anything; I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord."

The next day, Dr King stood on the balcony of his hotel room, and was shot in his right cheek. The bullet broke his jaw, went through his spinal cord, and killed him.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLongevity has its place, but I'm not concerned about that now, he had said, less than 24 hours earlier.

I've seen the Promised Land, I may not get there with you.

It really doesn't matter to me now, because I've been to the mountain top.

Did Dr King know what was coming?

The morning of the speech, Dr King flew from Atlanta, Georgia, to Memphis. The flight was late taking off.

"We're sorry for the delay," the pilot told the passengers. "But we have Dr Martin Luther King on the plane."

Bags had to be searched, in case someone left a bomb. Everything had to be double-checked.

"And," the pilot added, "we've had the plane protected and guarded all night."

In Dr King's life, death was never far away. It followed him; stalked him; appeared when he turned a corner.

"For a long time, King had been aware that white supremacists and local groups of Klansmen had been stalking him," says Dr King expert Professor Jonathan Rieder, author of Gospel of Freedom.

Getty Images

Getty Images"He knew there were plenty of people who wanted to take him out. The forces of white supremacy had killed many civil rights workers - and he was the most visible."

In 1956, Dr King's house was bombed during the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

More on the US civil rights struggle

In 1958, he was stabbed in New York by a mentally-ill black woman, and almost died. In 1963, in Birmingham, Alabama, he was attacked on stage by a white supremacist.

A year later, he went to the same city to join the campaign there. According to Professor Rieder, who spoke to his friends Andrew Young and Wyatt Walker, Dr King warned them before travelling.

"We're about to go into Bull Connor's town," he said (Bull Connor was a local politician opposed to the civil rights movement).

"And Bull Connor isn't playing. There's a good chance some of us won't come back alive."

So death cast a shadow over Dr King's work. But it wasn't just him, and his colleagues, who lived in danger. In the United States, the 1960s was a febrile, dangerous decade.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt was a time of riots (Harlem, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Detroit, others), war (Vietnam), and assassinations (John F Kennedy, Malcolm X, Dr King himself, Robert F Kennedy).

"This is what's going to happen to me," Dr King told his wife, Coretta, after JFK was killed in 1963. "I keep telling you, this is a sick society."

In the months before Memphis, says Professor Rieder, Dr King was in a "very fragile emotional state".

"He was feeling, at a political level, that America was descending into the opposite of the beloved community that he struggled for," he says.

"White racial backlash had spread across the north. George Wallace [Governor of Alabama], his nemesis from the south, was running for president.

"Younger generations of blacks and civil rights activists were turning away from his beloved doctrine of Christian non-violence. And he doubted, are we still relevant?"

That doubt - that despair, even - was revealed in a Virginia hotel room, seven months before he died. After a meeting with colleagues, Dr King was drinking alone when he woke them up, shouting.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I don't want to do this anymore!" he yelled. "I want to go back to my little church!"

He didn't go back, of course.

He kept going; kept fighting; kept demanding rights. And that is why, on a stormy April night, he found himself in the Mason Temple in Memphis, standing up for black workers. He was 39 years old.

"It doesn't really matter whether he's predicting his death in the next few days - but he is a man who knows that it's really close in time and space," says Professor Rieder.

"What is clear, though, is that he understands his life could end at any moment and he's looking back, reflecting on its meaning."

Towards the end of the Memphis speech, Dr King talked about the day he was stabbed in New York, 10 years earlier.

If he had sneezed, he said, he would have died, and therefore missed the Civil Rights Bill, the I Have A Dream speech, the movement in Selma, and other great moments.

"I want to say tonight," he told the crowd, "that I, too, am happy that I didn't sneeze".

So his final words were not just an acceptance that death was possible; or probable, even. They were an attempt to pass the torch; to keep the flame burning if - or when - he was killed.

"He's saying 'even if I don't make it, we will make it,'" says Professor Rieder.

"He's reassuring the movement that black people as a whole will overcome. In this process, he's embracing his sacrificial vocation.

"In preparing for death, he doesn't feel despondent. And in the end, he's providing an epitaph for the movement, as well as himself.

"The theme running throughout the speech is 'we have much to be proud of'. I read that as, even if I die, I have lived a good life. I have done my bit to bring us closer to the Promised Land."