Eddie Adams' iconic Vietnam War photo: What happened next

AP/Briscoe Center for American History

AP/Briscoe Center for American HistoryPhotojournalist Eddie Adams captured one of the most famous images of the Vietnam War - the very instant of an execution during the chaos of the Tet Offensive. It would bring him a lifetime of glory, but as James Jeffrey writes, also of sorrow.

Warning: This story includes Adams' photo of the moment of the shooting, and graphic descriptions of it.

The snub-nosed pistol is already recoiling in the man's outstretched arm as the prisoner's face contorts from the force of a bullet entering his skull.

To the left of the frame, a watching soldier seems to be grimacing in shock.

It's hard to not feel the same repulsion, and guilt, with the knowledge one is looking at the precise moment of death.

Ballistic experts say the picture - which became known as Saigon Execution - shows the microsecond the bullet entered the man's head.

Eddie Adams's photo of Brigadier General Nguyen Ngoc Loan shooting a Viet Cong prisoner is considered one of the most influential images of the Vietnam War.

At the time, the image was reprinted around the world and came to symbolise for many the brutality and anarchy of the war.

It also galvanised growing sentiment in America about the futility of the fight - that the war was unwinnable.

AP/Briscoe Center for American History

AP/Briscoe Center for American History"There's something in the nature of a still image that deeply affects the viewer and stays with them," says Ben Wright, associate director for communications at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History.

The centre, based at the University of Texas at Austin, houses Adams's archive of photos, documents and correspondence.

"The film footage of the shooting, while ghastly, doesn't evoke the same feelings of urgency and stark tragedy."

But the photo did not - could not - fully explain the circumstances on the streets of Saigon on 1 February 1968, two days after the forces of the People's Army of Vietnam and the Viet Cong launched the Tet Offensive. Dozens of South Vietnamese cities were caught by surprise.

Heavy street fighting had pitched Saigon into chaos when South Vietnamese military caught a suspected Viet Cong squad leader, Nguyen Van Lem, at the site of a mass grave of more than 30 civilians.

Adams began taking photos as Lem was frogmarched through the streets to Loan's jeep.

Loan stood beside Lem before pointing his pistol at the prisoner's head.

"I thought he was going to threaten or terrorise the guy," Adams recalled afterwards, "so I just naturally raised my camera and took the picture."

Lem was believed to have murdered the wife and six children of one of Loan's colleagues. The general fired his pistol.

"If you hesitate, if you didn't do your duty, the men won't follow you," the general said about the suddenness of his actions.

AP/Briscoe Center for American History

AP/Briscoe Center for American HistoryLoan played a crucial role during the first 72 hours of the Tet Offensive, galvanising troops to prevent the fall of Saigon, according to Colonel Tullius Acampora, who worked for two years as the US Army's liaison officer to Loan.

Adams said his immediate impression was that Loan was a "cold, callous killer". But after travelling with him around the country he revised his assessment.

"He is a product of modern Vietnam and his time," Adams said in a dispatch from Vietnam.

By May the following year, the photo had won Adams a Pulitzer Prize for spot news photography.

Despite this crowning journalistic achievement and letters of congratulation from fellow Pulitzer winners, President Richard Nixon and even school children across America, the photo would come to haunt Adams.

"I was getting money for showing one man killing another," Adams said at a later awards ceremony. "Two lives were destroyed, and I was getting paid for it. I was a hero."

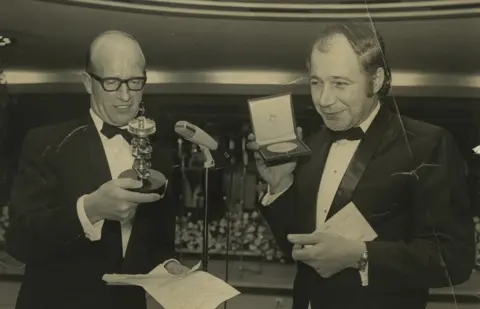

Briscoe Center for American History

Briscoe Center for American HistoryAdams and Loan stayed in touch, even becoming friends after the general fled South Vietnam at the end of the war for the United States.

But upon Loan's arrival, US Immigration and Nationalization Services wanted to deport him, a move influenced by the photo. They approached Adams to testify against Loan, but Adams instead testified in his favour.

Adams even appeared on television to explain the circumstances of the photograph.

Congress eventually lifted the deportation and Loan was allowed to stay, opening a restaurant in a Washington, DC suburb serving hamburgers, pizza and Vietnamese dishes.

An old Washington Post newspaper article photo shows an older smiling Loan sitting at the restaurant counter.

But he was eventually forced into retirement when publicity about his past soured business. Adams recalled that on his last visit to the restaurant he found abusive graffiti about Loan scrawled in the toilet.

Hal Buell, Adams' photo editor at the AP, says Saigon Execution still holds sway 50 years later because the photo, "in one frame, symbolises the full war's brutality".

"Like all icons, it summarises what has gone before, captures a current moment and, if we are smart enough, tells us something about the future brutality all wars promise."

And Buell says the experience taught Adams about the limits of a single photograph telling a whole story.

"Eddie is quoted as saying that photography is a powerful weapon," Buell says. "Photography by its nature is selective. It isolates a single moment, divorcing that moment from the moments before and after that possibly lead to adjusted meaning."

Adams went on to an expansive photography career, winning more than 500 photojournalism awards and photographing high-profile figures including Ronald Reagan, Fidel Castro and Malcolm X.

Despite all he achieved after Vietnam, the moment of his most famous photograph would always remain with Adams.

"Two people died in that photograph," Adams wrote following Loan's death from cancer in 1998. "The general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera."