The abuse victim who has protested in the same spot for 20 years

BBC

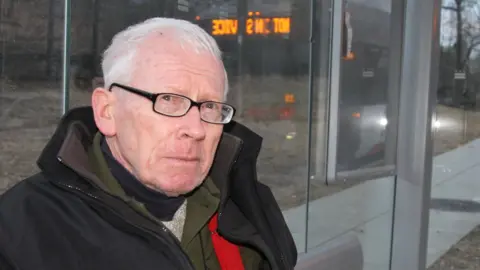

BBCJohn Wojnowski was abused by a priest during a Latin lesson 60 years ago. He has spent the past two decades protesting outside the Vatican Embassy in Washington DC. What keeps him going?

The most surprising thing about this protester is - he doesn't want to protest.

He doesn't want to spend eight hours a day on public transport, waiting for buses and trains, getting to and from Embassy Row in Washington DC.

He doesn't want to hold his sign in the cold, and the dark, and the snow, and the rain.

He doesn't want his face to freeze, his knees to ache, his fingers to turn numb.

He was 54 when the protest started; he turns 75 in April. He has spent almost a third of his life here, on his own, holding a sign outside the Vatican Embassy.

"Of course I want to stop," he says. "But they made it personal."

As day turns to night, and the temperature sinks, John sits in a bus shelter opposite the embassy, taping three broom handles together.

It's 4:30pm; he left home in Baltimore County, around 35 miles north, at 11:30am.

"I waited 45 minutes for the first bus," he says. "Then half an hour for the second bus."

From there, he took a train to Washington's Union Station, a metro to Dupont Circle, before catching a third bus up the hill to the embassy.

When he started protesting 20 years ago, John lived eight miles away in Bladensburg, Maryland, and drove a car. He would protest twice a day: a morning shift followed by the rush hour.

Around 10 years ago, his car gave out, followed by his knees. So he started using public transport: bus, metro, bus up the hill.

A year ago he left Bladensburg to live with his son in Baltimore County. He no longer protests daily; instead, it's "once, twice, maybe three times a week".

"I try to stay a couple of hours, but it's unpleasant in the dark," he says. "In summer I stay longer."

Before he moved to Baltimore County, John came to the embassy every day. After around eight years, he started taking an annual break to see his daughter's family in California.

When John's mother, who lived in Poland, became sick, he didn't visit. When she died, he missed the funeral.

"I just couldn't leave here," he says, which takes us back to the start.

Why not?

John was born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1943. His father trained to be a priest in Rome before becoming a Polish diplomat.

After World War Two, Poland's new government sent John's father to Naples, then Milan. "He was a communist, an intellectual, he spoke Italian," John says.

John calls his younger self a "happy, well-adjusted young Catholic". And then, in the Italian village of Cuzzago, a parish priest invited him for a Latin lesson.

"The priest was absolutely direct," says John. "He told me to sit at his desk, I sat. He told me he was going to tutor me, he never opened a book.

"The very first thing he did was put his hand on my knee."

John was 15 years old. "I don't remember getting out," he says. "I just remember being outside, feeling so terrible.

"The feeling was so profound, so final. The feeling was - it was my fault, I have ruined my life."

Years later, he learned that his younger brother - who had come to ask the priest a question - saw John being abused.

John didn't tell anyone he'd been attacked. In fact, he repressed the memory for almost 40 years. But the abuse changed him.

"I like girls - nothing more beautiful than girls," he says. "After it [the abuse] happened, I never talked to girls. I avoided everyone."

His father took him to a Catholic university in Italy for a psychological test. "I guess nothing came out," says John. He left high school early.

Aged 18, John moved to Canada; aged 20, he moved to the US. He joined the army for three years, before becoming a US citizen and training as an ironworker (he retired before his protest began).

He met his wife during a visit to Poland. They had a daughter in 1971 and a son in 1975. John and his wife separated more than 20 years ago.

"She suffered the most," he says. "I destroyed her."

They still talk every day - he's expecting a call any minute - but she lives in Florida. John has few friends, he says, and no hobbies.

In 1997, John read about a case in Dallas, Texas - a jury awarded $120m to a group of altar boys abused by a Roman Catholic priest [the settlement was later reduced to $31m].

As John learned more, his memory of that day in Cuzzago - the priest, the Latin lesson, the abuse - came back. He decided to contact the church, and is honest about his motivation.

"It's embarrassing," he says. "But I thought: 'I was molested by a Catholic priest - I could use $20,000.'"

He went to see a priest in Maryland. Not his local one - his wife went to church, and he couldn't face the embarrassment - but another nearby.

"I parked my car in a shopping centre far away," he says. "I found the church, found the priest, went inside his office.

"He sat down. I could not sit down. It took maybe 15 or 20 minutes to say: 'I was abused by a Catholic priest'."

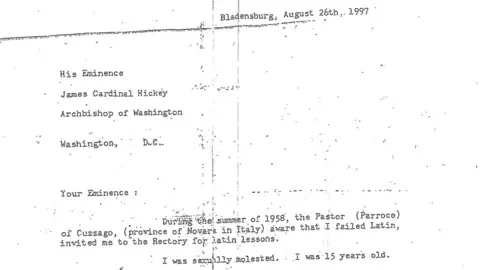

The priest, Father Michael Blackwell, was helpful, and told John to write a letter to the Archbishop of Washington, Cardinal James Hickey.

"I bought a typewriter," says John. "An old, big one. I typed the letter I don't know how many times."

After a month, a different bishop wrote to John, asking for more details. John did so, then waited.

"A month went by with no answer," he says.

"I wrote a second letter. Two months went by, no answer. I wrote a third letter. Three months went by, no answer."

The Archdiocese of Washington said it contacted the diocese where the abuse happened "immediately".

So, while waiting for a response, John bought a big piece of plywood. He drew a question mark on it, wrote a small caption, and stood outside the Vatican Embassy.

Soon afterwards, the bishop, William Lori, wrote back. The priest from Cuzzago was dead.

The church offered to pay for therapy and, it says, encouraged John to contact the Italian diocese. Bishop Lori offered prayers, but not compensation.

John had already been to therapy two or three times, arranged by Father Blackwell. Now, he decided, it was time for protest.

He made a sign - "My life was ruined by a Catholic paedophile priest" - and, in April 1998, went back to the embassy. After years of shame, and repressed memory, he told the world what happened.

"You cannot imagine how difficult it was, how sad," he says. "I was miserable holding the sign. You cannot imagine how terrible it felt."

Twenty years later, John is still there, on the pavement, holding his sign. The words have changed, but the sentiment remains.

John Wojnowski

John WojnowskiJohn is a short, slight man. He talks in a Polish accent with occasional Italian rhythm. Sometimes he stammers; other times, he stops mid-sentence and stares into the distance.

He is polite, and smiles when saying hello. He can also be eccentric - recently, he stuck a letter to the embassy door using stickers from a bunch of bananas.

"Parasitic and cowardly banana state," said the bottom of the letter.

Holding a sign, every day, on one of Washington DC's busiest roads, guarantees attention. Six months after his protest began, a local paper approached him. He spoke to them but declined to give his name.

"I didn't want my mother to find out what I was doing," he says. "She was a very religious old lady, going to church every day. I didn't want to give her the pain."

When the article was published, his name was there - in the headline, in the intro, in the caption. He thinks the church leaked it.

The Archdiocese of Washington is unable to comment on the accusation - no-one who worked in the communication department in 1998 is still there.

But John says that when he saw his name in black and white, the dispute became personal.

Other long-term protests

- Peace protester Brian Haw camped outside Parliament in London for 10 years, from 2001 to 2011. He died the same year

- Jacqueline Smith has protested in Memphis, near the spot where Martin Luther King was killed, since 1988

- Concepcion Picciotto, a peace campaigner, camped outside the White House from 1981 until her death in 2016

When John started his protest, it was four years before the Boston Globe exposed Roman Catholic abuse and 17 years before the Oscar-winning film Spotlight.

The extent of abuse in the Roman Catholic church was not widely known. Early on, says John, an angry passer-by called him a "coward hiding behind a sign".

"He repeated it five or six times," says John.

Twice, his car suffered a flat tyre while parked near the embassy. "I cannot say who did it," says John.

Now, though, he gets more support. Cars beep their horns. Occasionally, people offer him cash. Does John - in some way - feel vindicated?

"Of course, I'm glad," he says. "Many people thank me for what I'm doing. But I do it for myself."

One of those people is Christine de Fontenay, who protests against President Trump on the same road. Christine, 74, hands over a printed letter entitled: "John Wojnowski, America's prophet."

John, says the letter, has played "such a significant part" in bringing about "the colossal change in the world's conscience and consciousness about paedophilia".

"On behalf of the world - especially its children - I say thank you to him," the letter concludes.

John has never hired a lawyer. "There is a statute of limitations," he insists. "Legally, I have no recourse."

Likewise, he hasn't chased his case in Italy; he thinks pursuing it in the US should be enough. "This is one church," he says.

If that seems an odd rationale, he has tried to get Rome interested in his case.

In 2015, when Pope Francis visited Washington, John handed a letter to Vatican's then Nuncio [ambassador] Carlo Maria Vigano. The Nuncio took the letter, and they spoke briefly, but that was it.

The Apostolic Nunciature - the formal name for the embassy - was approached for comment but did not respond. Archbishop Vigano left his post, as required, when he turned 75 in 2016.

So - if the church did offer compensation - would John stop protesting? "Of course," he says.

And if they don't, will he continue? "Of course," he says again. "It is a challenge." But does he ever go home, cold and tired, and think about giving up?

"No, absolutely not," he says. "They made it personal. They insulted me. Would you give up?"

And, with that, the interview ends. Christine, the Trump protester, has offered John a lift home.

He unties the banner, untapes the broom handles, and heads for Baltimore County. But he'll be back - knees aching, injustice burning, 20 years outside the embassy and counting.

Full response from the Archdiocese of Washington

All reports of suspected abuse or even questions about possible abuse are taken seriously by the Archdiocese of Washington.

When people come forward with an allegation of abuse, the archdiocese immediately tries to assist them with healing, and we have offered counseling and pastoral support when someone makes an allegation that is credible.

We have found that each person's needs are different and we work to meet their needs, while always respecting their privacy. The Archdiocese of Washington has had a child protection policy since 1986 and our long-standing and public efforts in this area are outlined here.

The Archdiocese of Washington has reached out to Mr Wojnowski before, a fact that has been reported publicly in multiple news articles that have appeared over the years. In 1997, Mr Wojnowski contacted the Archdiocese of Washington about an incident which at the time, he said occurred in Italy forty years earlier.

Upon receiving his letter, the Archdiocese of Washington immediately contacted the diocese in Italy where the abuse allegedly occurred and which would be responsible for that priest's conduct in an effort to find out what happened.

It was found that the priest allegedly involved passed away many years ago. This information was provided to Mr Wojnowski and he was encouraged to contact the diocese in Italy to pursue his claim of abuse.

Additionally, the Archdiocese of Washington, in our concern for Mr Wojnowski's situation, offered him free counseling and therapy, which he has declined to accept, but the offer still stands.