Why so many sexual harassment cases in US, not UK?

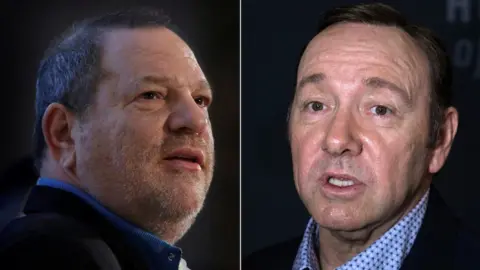

Reuters / AFP

Reuters / AFPThere are huge differences between UK and US media law - does this explain why more Americans are being accused of sexual harassment?

On 5 October, Harvey Weinstein was accused of sexual abuse and the dam broke.

Since then, dozens of well-known Americans have been accused of sexual misconduct of some kind. This isn't drip-drip. It's a flood.

The list includes film stars such as Kevin Spacey, politicians such as Roy Moore, and journalists such as Mark Halperin.

The deluge of allegations swelled this week, engulfing big media names.

While people in other countries have also been accused, the majority of cases are American.

One reason could be US media law and how it differs from other countries.

In the UK, there is a key point in libel law that explains a lot.

When someone sues, they don't have to prove the story is wrong.

The publisher - for example, the newspaper or website - has to prove their story is right.

This means, before publishing, the media needs a water-tight case. To accuse someone of sexual misconduct, they would normally need proof (such as a recording) or a witness prepared to testify in court.

In cases of sexual misconduct, both things are hard to find.

There were, for example, rumours of Jimmy Savile's sexual abuse for years. Louis Theroux even asked Savile about them in 2000.

But the British media - worried about being sued - didn't publish. It wasn't until Savile died that ITV broke the story (in UK law, a dead person cannot be defamed).

You don't even need to name someone to be sued in the UK.

In 2012, BBC Newsnight wrongly linked Lord McAlpine to child sex abuse, without naming him.

He sued and within 13 days won £185,000 in damages.

Defamation in the UK - the main defences

- Truth

- Honest opinion

- Protected by privilege (for example, court reports are protected)

- Published on a matter of public interest

In the US, it's far harder to sue for libel. The reason is 226 years old, but as relevant as ever.

The first amendment to the US constitution - adopted in 1791 - protects freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

It means American media law is "radically different" to the UK, says Stuart Karle, a professor at Columbia Journalism School in New York and former general counsel for the Wall Street Journal.

"In the US, the burden is on the plaintiff - the person alleging that he or she has been defamed - to prove the statement is false," he says.

So - compared to the UK - the burden of proof is flipped. Americans are less likely to sue, so US media are more likely to break the story.

Indeed, a New York Times editorial in May said "hardly anyone jousts with the (New York) Times when it comes to formally asserting libel".

And - for celebrities - there's another hurdle to clear when suing in the US.

When a public official (such as a government employee) or public figure (such as a celebrity) sues for libel, they must prove "actual malice".

"Actual malice basically means the journalist lied," says Professor Karle.

"Either the journalist published a story they knew was false - or they acted with reckless disregard over whether it was true or false.

"That basically means - you lied."

But - despite the bar being higher - it doesn't mean American media has carte blanche. And, when they do get it wrong, it can cost millions of dollars.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 2014, Rolling Stone magazine covered an alleged gang rape at the University of Virginia in 2012.

The story was retracted in 2015 and a university official - who handled sexual assault cases - sued for defamation. She was awarded $3m in damages.

Further back, a prosecutor sued the Philadelphia Inquirer over articles published in 1973. He won $34m.

"Sometimes you hear 'in the United States, reputation isn't valued'," says Professor Karle.

"But the US laws are highly protective of reputation. The damages can be massive - far, far greater than one could get in the UK.

"So you have more (defamation) cases in the UK and more stories that aren't published or broadcast.

"But in the US, if a plaintiff wins, the potential damages are in the millions - or tens of millions."

For this reason - and for reasons of good journalism - American media often goes to great lengths to verify accusations.

In their recent story about television presenter Charlie Rose, the Washington Post spoke to eight women - three of them on the record.

In breaking the story about comedian Louis CK, the New York Times reported accusations from five women - four of them named.

And - in an article about New York Times reporter Glenn Thrush - Vox writer Laura McGann recounted her own experience, interviewed three other women, and spoke to 40 people in the wider media.

Which system is better - the UK or the US - depends on your point of view.

If you've been wrongly accused, you may yearn for the British system - where publishing is riskier.

If you're a victim, you may prefer the US system - where the constitution protects freedom of speech.

Either way, the effect is clear.

The US has a flood of cases. In the UK, it remains drip-drip.