Why are US mass shootings getting more deadly?

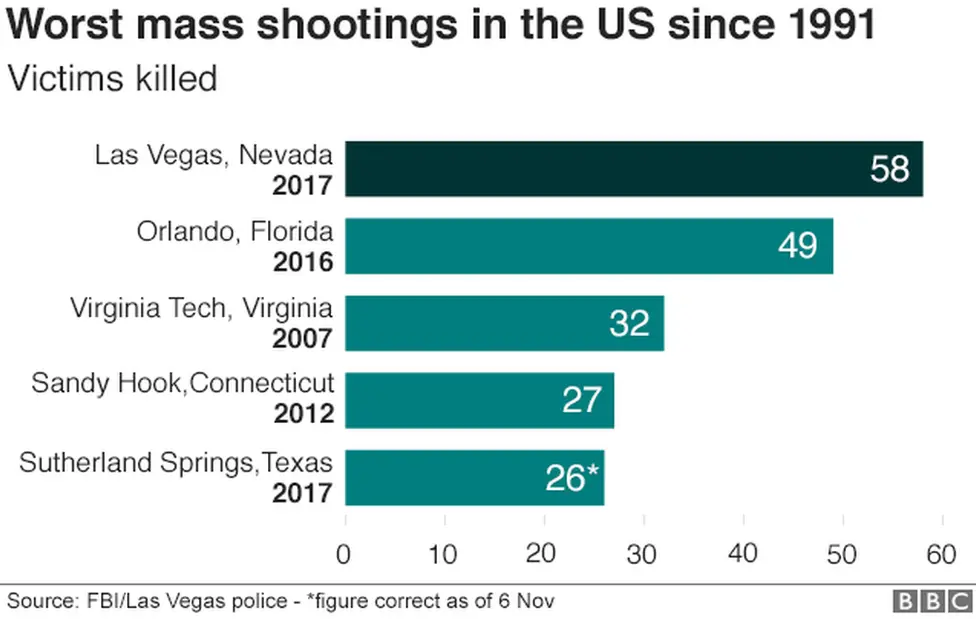

Three of the worst five shootings in modern US history have happened in the last 16 months.

It began - more or less - with 13, the number killed in 1949 in Camden, New Jersey, one of the earliest mass shootings in the US. An army veteran, Howard Unruh, killed his neighbours.

Over the next several decades, the numbers went up: 16 in Austin, Texas, on a campus in 1966, and 21 slain at a McDonald's in San Ysidro, California, in 1984.

The past month or so have been especially brutal, as two attacks unfolded - in Las Vegas (58 dead) and Sutherland Springs, Texas (26). They followed a June 2016 assault in an Orlando nightclub in which 49 people were killed.

The reasons for this disturbing trend are many and complex, and people across the US and around the world have struggled to understand the violence.

Here analysts discuss some of the factors that may lie behind the grim numbers:

Weapons are more powerful - and shoot faster

The shooters have increasingly been using guns with high-capacity magazines, allowing them to fire off dozens of rounds without having to reload.

"There are more people being shot in a shorter amount of time - with more bullets in them," explained Harvard School of Public Health's David Hemenway.

Adam Lanza, who killed 26 people at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut, in 2012, and James Holmes, who killed 12 in Aurora, Colorado, that year, both used weapons with this feature. The data's clear: the number of killings in individual attacks goes up when assault rifles are used.

Researchers have also examined the laws: a ban on semiautomatic military-style assault rifles and large-capacity magazines was passed in 1994. It was lifted in 2004.

Experts said lifting the ban helped to usher in a new era of mass shootings. With these weapons, individuals could shoot faster and for longer periods of time - and consequently were able to kill more people in their attacks.

In addition states have their own laws. After the Sandy Hook massacre, a Connecticut law was passed that banned some semiautomatic rifles.

Other states loosened their gun laws, however. In Georgia, for example, a law was passed that allowed people to carry weapons in school classrooms, nightclubs and other places. Experts at the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence wrote that people in states with stricter gun controls tended to see less gun violence.

Assailants choose their sites more carefully

Attacks are now carried out in places with a large number of people - such as a Las Vegas concert venue with 22,000 people. "With that type of crowd, the shooter didn't even have to aim," said University of Central Florida's Jay Corzine.

Most of the people who carry out mass shootings plan the attacks carefully, according to Homicide Studies.

"They're doing their homework," Corzine explained. Preparing the groundwork, he said, means the shooters kill more.

The gunman who opened fire at a Batman screening in Aurora, Colorado, in 2012 "thought a movie theatre would lead to higher fatalities", said the University of Alabama's Adam Lankford.

The shooters are inspired by media accounts

Coverage of mass shootings - like the assaults themselves - have exploded in recent years. Shooters post on social media before the attacks and sometimes while the assaults are underway.

Media organisations create live pages and provide 24/7 coverage of an assault. In addition journalists often focus on the killers, providing details about their lives and unintentionally contributing to a glorification of these individuals.

Yet overall, say experts, the stories did not cause an increase in the number of deaths in the assaults. "I've seen media accounts of mass shootings for the past 25 years, and the uptick of high casualties has been pretty recent," said Corzine. Still the coverage gives people ideas.

"Mass shootings are contagious," said Gary Slutkin, founder of a Chicago-based organisation, Cure Violence. "People see what other people do, and they follow that."

The shooters compete with each other

Dylan Klebold, one of the attackers at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, in 1999, described their goal: "the most deaths in US history…we're hoping."

As Lankford explained: "This really is a race for notoriety - to be bigger and better than the attackers who came before you."

Becoming famous as a mass shooter may seem like a sick glory. Yet it holds an allure for some. "It's, 'Well, yeah…,'" Slutkin said, describing how these individuals consider the possibility of fame and spend little time contemplating the likelihood of their own grisly fate: "It isn't all the way thought through."

"We all want to be known after we're dead," he explained.

"It shows how strong that circuit is."