Saudi Arabia: Just how deep are its troubles?

AFP

AFPOnce famous for being tax-free, Saudi Arabia has announced it is trebling its Value Added Tax (VAT) from 5% to 15% and cancelling the monthly living subsidy from next month.

The moves come as global oil prices have crashed down to less than half what they were a year ago, slashing government revenues by 22% and putting major projects on hold.

Saudi Aramco, the state oil company, has already seen its net profit fall by 25% in the first quarter of this year, mainly due to the collapse in crude oil prices.

"These measures reflect a drastic need to rein in spending and to try to stabilise weak oil prices," says Gulf analyst Michael Stephens. "The Kingdom's economy is in a terrible state and it will take some time to recover any sense of normality."

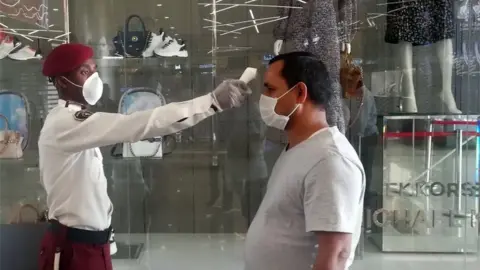

AFP

AFPCovid-19 is currently wreaking havoc with an economy that depends in large part on millions of unskilled expatriate workers from Asia, many of whom live in crowded, unsanitary conditions.

Meanwhile the crown prince, while still largely popular at home, remains something of a pariah in the West due to lingering suspicions over his alleged role in the killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

International investment confidence has never fully recovered from his grisly murder and dismemberment by government agents inside the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul in 2018.

Then the war in neighbouring Yemen has bled Saudi coffers for more than five years now with no tangible gains, and a spat with Qatar has wrecked the surface unity of the six-nation Gulf Arab Cooperation Council (GCC).

So, is Saudi Arabia in serious trouble?

'Built-in resilience'

First, some perspective. The coronavirus pandemic has wrecked economies all over the world and Saudi Arabia is no exception.

It does have a sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund, to fall back on, with an estimated value of $320bn (£260bn; 295bn euros).

It also has Saudi Aramco, the majority state-owned oil company, valued last year at $1.7 trillion - equivalent to the combined worth of Google and Amazon at the time.

Reuters

ReutersBy selling off just a tiny fraction - 1.5% - Saudi Arabia raised more than $25bn in the biggest share listing in history.

"Saudi Arabia has quite a lot of resilience built in," says Sir William Patey, former British Ambassador to Riyadh between 2007-10. "They have a lot of reserves to keep them going and they could still come out of this oil price slump with their market share intact or even improved."

The strategic threat to the country from Iran appears, at least for now, to have subsided following last September's missile attack on its oil refineries and then the later US assassination of Iran's Revolutionary Guards commander Qasem Soleimani in January.

This month the Pentagon has withdrawn Patriot missile batteries sent as an emergency defensive measure. The latent domestic terrorist threat from jihadists linked to the Islamic State group (IS) and al-Qaeda, while not completely vanquished, has been largely reduced.

Yet Saudi Arabia still faces some serious and mounting challenges as follows:

The Economy

This week's austerity announcements will have come as unwelcome news to many Saudis, who had been looking forward to a brighter future under grandiose plans to diversify the economy away from oil income.

Even the finance minister himself referred to them as "painful measures". They are intended to save $26bn but the combined damage caused by the Covid-19 virus and the oil price drop has already reportedly cost the Saudi central bank a similar figure in just the month of March alone.

AFP

AFPIn the first quarter of this year there is a budget deficit of $9bn.

This is not the first time Saudi Arabia has had to hit the austerity button. In May 1998 I attended the GCC summit in Abu Dhabi when then Crown Prince Abdullah gave a stern warning to his fellow Gulf Arab rulers.

"Oil is at $9 a barrel," he told them. "The good times are over - they're not coming back. It is time for all of us to tighten our belts."

In fact, the oil price later rose to more than $100 a barrel, but not before the government had introduced a hiring freeze and a nationwide slowdown in construction projects.

This time it may be more serious.

Coronavirus and oil price collapse have torpedoed projects all across the kingdom, calling into question whether the crown prince's much-vaunted Vision 2030 programme can still be achieved.

AFP

AFPThe programme, which aims to wean the country off its historic dependence on both oil revenue and expatriate labour, has at its heart a massive $500bn futuristic city in the desert called NEOM.

Officials say this is still going ahead but most analysts believe cutbacks and delays are now inevitable.

"The private sector in particular will be hardest hit" by the austerity measures, says Michael Stephens.

"The kingdom's emergency measures are harming the job creators, which will make it even more difficult to recover in the long term."

Global standing

Saudi Arabia's global reputation was critically damaged by the Khashoggi murder and the initial botched cover-up.

Even the Saudi ambassador to London called it "a stain on our reputation".

The subsequent trial and convictions, which allowed some of the leading suspects to walk free, have attracted further criticism from human rights groups and the UN special rapporteur into extrajudicial killings.

Reuters

ReutersBut Saudi Arabia is simply too large and too important an economy for the world to ignore.

Recently it has been looking to acquire strategic stakes in high-profile investments such as its current bid to acquire 80% of Newcastle United Football Club, a move strongly opposed by Khashoggi's widow, Hatice Cengiz, on ethical grounds.

The Yemen War, prosecuted in part from the air by Saudi warplanes supplied by the US and Britain, has seen alleged war crimes committed by all sides.

But the civilian death toll caused by those air strikes has led to mounting criticism in Washington and elsewhere.

The war has achieved very little, while wrecking what was already the poorest country in the Arab world. Support for Riyadh on Capitol Hill has been declining.

EPA

EPAThe two big allies that Saudi crown prince and de facto ruler Mohammed Bin Salman (known as MBS) has been able to count on were Presidents Trump and Putin.

But this year, by opening up the oil taps and deliberately flooding the market, he has managed to annoy both leaders by inflicting damage on their domestic economies.

Relations with Iran remain in a state of Cold War and they are little better with neighbouring Qatar.

At home the crown prince has been moving with extraordinary speed to push forward a programme of social liberalisation, lifting the ban on women driving and allowing previously unheard-of freedoms like cinemas, mixed-sex concerts and car rallies.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSaudi Arabia today is, on the surface, a far less austere place than it used to be.

But behind the scenes political repression has accelerated, with anyone daring to even question his policies risking arrest and imprisonment on charges of "threatening national security".

Judicial beheadings continue apace and the country is still one of the most heavily criticised by human rights groups.

All of this means that while Saudi Arabia remains a huge player in the international economy - it is due to host the next G20 summit in November - its allies see it as an awkward and sometimes embarrassing partner.

Power

At 34 years of age, Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman appears to be unassailable. He has the backing of his 84-year old father, King Salman, and he has systematically removed any potential rivals to the throne.

His once-powerful cousin Prince Mohammed Bin Nayef, whom he replaced as crown prince in a palace coup in 2017, is just one of many senior figures to have been detained and disempowered.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere are grumblings amongst older, conservative Saudis that MBS's maverick and unconventional policies are leading the country down a dangerous path. Yet there is also talk of "a climate of fear" with no-one daring to speak out and risk arrest.

In contrast to MBS's reputation abroad, his standing at home remains largely popular, especially amongst the youth.

"They are the ones to have benefitted the most from his liberalisation," says Sir William Patey. "MBS has a big constituency there."

Part of that popularity rests on a newfound Saudi nationalism, embodied in the youthful crown prince himself.

But a large part of it also rests on a widespread optimism that he can deliver them a golden economic future.

If those dreams fall flat and five years from now those jobs never materialise, then the absolute power of the Saudi monarchy may start to look a little less secure.