Islamic State group: Could it rebound from caliphate defeat?

Manbar.me

Manbar.meIn short: yes, but not in the same form.

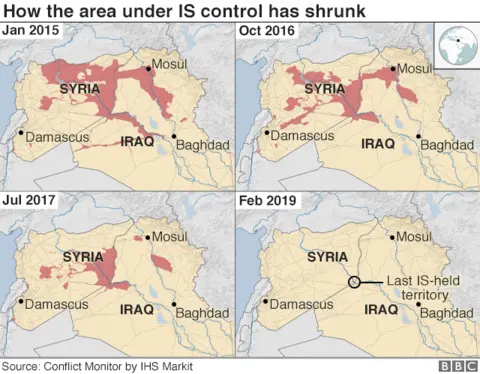

The jihadist terror group's self-proclaimed "caliphate", which once ruled over nearly eight million people across Syria and Iraq, has been all but eliminated.

The temptation for triumphalism in Western capitals is overwhelming. It has taken four and a half years of relentless military pressure by a 79-nation coalition to get to this point. It has cost billions of dollars and thousands of lives, many of them civilian.

But people who have access to secret intelligence on the Islamic State (IS) group's activities and intentions are calling for caution.

At the recent Munich Security Conference, Alex Younger, the chief of Britain's secret intelligence service (MI6) - an organisation that was frankly caught completely off-balance by IS's lightning advances in 2014 - said this:

"The military defeat of the 'caliphate' does not represent the end of the terrorist threat. We see it therefore morphing, spreading out... within Syria but also externally... This is the traditional shape of a terrorist organisation."

Speaking at the same event, German Defence Minister Ursula von der Leyen assessed that IS was currently going deeper underground and building networks with other terrorist groups.

Gen Joseph Votel, who runs US Central Command, has warned that, although the IS network is dispersed, pressure must be maintained or its components will have "the capability of coming back together if we don't".

Reuters

ReutersEstimates of the number of IS fighters who have dispersed across the Syria-Iraq arena range from 20,000 to 30,000, many of whom will be unwilling to return to their home countries for fear of prosecution.

There are also small concentrations of fanatical IS-linked militants in Libya, Egypt, West Africa, Afghanistan and the southern Philippines. Already in Iraq there is evidence of IS militants mounting increasingly bold attacks in the northern provinces.

So far, so grim. But let's have a look at what originally propelled IS to its early victories and lightning conquests in 2013/14 and assess whether it could do so again.

Out of the wilderness

IS grew out of al-Qaeda in Iraq, an insurgent group formed from an alliance of convenience between disgruntled and out-of-work Iraqi military and intelligence officers with idealistic jihadists flooding in from around the Arab world and elsewhere.

The calling card of Al-Qaeda in Iraq was what it said was a religious duty by all Muslims to come and resist the US occupation of Iraq.

But then its brutality and intolerance (e.g. chopping off the fingers of anyone caught smoking cigarettes) so alienated the Iraqi tribes that they sided with the government and drove al-Qaeda out into the wilderness.

Iraq's Shia-led government then squandered this gain by embarking on a systematic programme of discrimination against Sunni Muslims.

By the summer of 2014 they felt so disenfranchised that IS (a Sunni extremist movement) was able to practically walk into Iraq's second city of Mosul unopposed.

Couple this with a weak, demoralised Iraqi military, whose senior officers deserted their own troops ahead of the IS advance, and you had all the ingredients of an IS takeover of a third of Iraq.

Next door in Syria, with the civil war still raging, there was enough chaos and confusion for IS - as the most ruthless and ideological of all insurgent groups - to carve out large areas of control.

Islamic State 2.0

So could this happen again? Yes, and no.

It is highly unlikely that a physical "caliphate" of any size would be allowed to be reconstituted. Yet many of the factors that fuelled IS's early success are still there.

Iraq is awash with sectarian Shia militias, some funded, trained and armed by Iran. There are disturbing reports of Sunni villagers being dragged from their homes and - in some cases - falsely accused of supporting IS.

In some places, Shia revenge squads stalk the streets at night with impunity.

Iraq desperately needs a national reconciliation process and inclusive government if it is to avoid a regenerated IS 2.0. Yet there is little sign of this happening in practice.

In Syria, the factor that sparked that country's catastrophic civil war now sits victorious in his palace in Damascus.

President Bashar al-Assad, saved from defeat by his Russian and Iranian allies, appears more secure than ever.

Most Syrians are now too exhausted to oppose him. But the atrocities committed by his regime, on an industrial scale, will continue to propel some towards armed resistance, and IS will be looking for ways back into the Syrian battle space.

Further afield and globally, wherever there is a perception of bad governance, of disenfranchisement, of religious persecution against Muslims or where large bodies of alienated young men feel their lives lack purpose, there will always be opportunities for recruiters to the "cult" of IS.

Its caliphate is over - its dangerously infectious ideology is not.