Warsaw summit: Why Iran is the elephant in the room

AFP

AFPThe US decision to host a Middle East conference in Warsaw looks set to be a curious diplomatic occasion. But why is this gathering of mainly Western and Arab governments being held in the Polish capital? Poland, which is co-hosting the conference, is not known for its deep involvement in the Middle East's myriad problems.

But it is an active member of the Nato alliance, and its dark history at the hands of Russia gives it good reason to cosy up to Washington. Poland is hosting one of the US anti-ballistic missile sites in Europe.

Indeed some Poles are eager to see a large fully-fledged US military base - what some have dubbed "Fort Trump" - on their soil. So co-hosting this would-be US diplomatic extravaganza makes clear sense to them.

But one is left with the nagging thought that this meeting is in Poland primarily for one reason - none of Washington's other close partners in Europe were terribly eager to host it.

The gathering has prompted a collective yawn in European diplomatic circles. Even at this late stage it is uncertain who exactly will turn up and at what level many countries will be represented.

The genesis of this gathering was a proposal by the Americans to have an international meeting to increase the pressure on Tehran. But this idea was quickly revised since there was little enthusiasm among some of Washington's Western European allies.

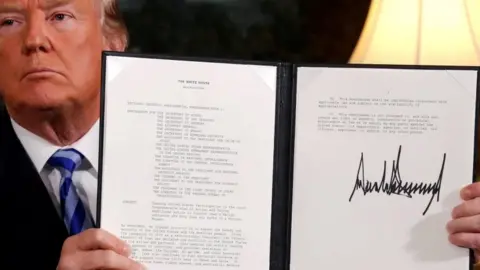

Indeed it became clear that putting the spotlight solely on Iran might simply highlight the divisions in the Western camp in the wake of the Trump administration's decision to pull out of the nuclear agreement - the JCPOA - with Tehran.

Reuters

ReutersSo instead the agenda has been broadened with the meeting now billed as a ministerial aimed at "Promoting a Future of Peace and Security in the Middle East".

Iran is not named on the agenda which includes broad thematic issues like humanitarian and refugee challenges, missile proliferation and 21st Century threats like cyber and terrorism.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict will not be on the agenda - the Palestinians are not attending since they are boycotting the Trump administration.

So who will go and at what level will they be represented?

We may not know that until ministers and officials actually turn up.

The Americans will be represented by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo but Vice-President Mike Pence and the president's son-in-law, Jared Kushner, (architect of the administration's yet to be revealed Middle East peace plan) will also probably attend.

British Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt will be there - at least for the opening session.

Other major European players may be represented at a lower level.

AFP

AFPIsraeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is heading to Warsaw - according to Polish sources - and several Arab governments will send delegations headed by ministers, including Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Jordan, Kuwait, Bahrain, Morocco, Oman and the United Arab Emirates. Egypt and Tunisia are expected to send deputy-ministers.

Indeed this could be the first major diplomatic gathering where Israel and the moderate Arab States have sat down to discuss regional security since the Madrid talks during the early 1990s. Some aspects of the peace process will inevitably come up but Iran is still likely to be a major area of discussion.

There is a fundamental division amongst the participants here. The US, Israel and many of the moderate Arab States see Iran as a malevolent influence in the region, seeking to expand its role at every opportunity. They were sceptical about the 2015 nuclear deal that was intended to constrain Iran's nuclear activities.

Israel in particular stands with the US and the Saudis here.

It is confronting a growing Iranian military presence in Syria and Lebanon. It is actively engaged in a battle of attrition against Iranian forces and proxy militias in the region.

Mr Netanyahu is likely to argue that Iran should not be looked at through the prism of divisions between the US and Europe over the nuclear deal.

Instead he will argue that it is European values that are at stake. Iran's behaviour - its support for terrorism; its human rights abuses, the detention of foreign nationals - are all issues that should matter to European governments.

AFP

AFPIt is certainly true that foreign ministries in London, Paris and Germany are concerned about Iran's regional behaviour and its developing missile programmes. But there is uncertainty about quite what to do about them.

For the Europeans, maintaining what they see as the nuclear deal's brakes on Iran's nuclear activities is the paramount concern. For Washington, Israel and the moderate Arabs this is insufficient.

But Europe is distracted by Brexit and a host of other issues. Persistent tensions with the Trump administration and the US president's erratic policy decisions - the move to pull US forces out of Syria and the threatened draw-down in Afghanistan for example - only make matters worse.

The US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and more recently, the INF disarmament treaty, only flags up the perceived unreliability of Washington in many European eyes.

So whatever the multiple problems in the Middle East, this gathering may tell us just as much about the divisions in the Western camp which seem to be getting worse rather than better.