The horrors of Yemen's spiralling cholera crisis

ICRC Yemen

ICRC YemenChildren dying in hospital hallways. Four sick people crammed into one bed. Patients connected to intravenous drips while sitting in their cars because the hospital is over capacity.

Welcome to the Yemeni healthcare system in 2017.

The bizarre and haunting scenes I have witnessed recently in the capital, Sanaa, are the consequences of a health catastrophe spiralling out of control.

In a country where vital infrastructure is devastated by a brutal and ongoing war, the toll of this cholera outbreak grows by the thousands every day.

EPA

EPADespite the sickness, the hospitals do not smell of vomit and diarrhoea. Instead, they smell of body odour - a testament to the overcrowding in many of these facilities.

Packed rooms and hallways are quiet. Patients look at us, with no expression. Parents hold the hands of their children, some of whose eyes roll into the back of their heads.

Overburdened medical staff do what they can but often do not have enough supplies or knowledge - two reasons cholera has spread so fast.

The cholera outbreak has infected more than 200,000 people across Yemen, and it appears that 500,000 could eventually become sick. More than 1,300 people have already died.

EPA

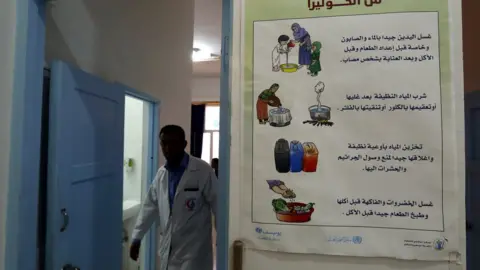

EPAThe disease should not be so ferocious. Preventing cholera is pretty simple in theory: wash your hands with clean water, drink clean water, and eat food that has been boiled or cooked.

But clean water in Yemen is a luxury. Municipal workers in Sanaa have not been paid in months. And so we have no electricity, rubbish piling high in the street, and a crippled water system.

The sewer system stopped working on 17 April. Ten days later, cholera hit.

Reuters

ReutersA massive response is needed, and not nearly enough international attention is being paid to what is going on here.

Yemen was until relatively recently a functional country.

Sitting on the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula, it has always had its shortcomings, but the education and health systems were working. Clean water and electricity ran 24 hours a day. Rubbish was collected.

In an astonishingly short period of time, though, those pillars of a healthy society crumbled, beginning with the Arab Spring and accelerating during today's full-blown war.

Violence is now part of life; I hear air strikes even as I write this.

EPA

EPAHospital systems have collapsed, with medical staff no longer paid. The staff who remain are overwhelmed.

My organisation, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), is currently providing care to nearly one in five cholera cases in the country - the biggest single provider of case management and infection control.

The ICRC has flown in five charter planes carrying large quantities of chlorine, IV fluids and other medical supplies in recent days. ICRC health staff and engineers are supporting 17 cholera treatment facilities around the country. We are improving hygiene and sanitation conditions, and raising cholera awareness among the general public.

Alexandre Faite/ICRC

Alexandre Faite/ICRCWe provide what we can, where we can. But even with similar work being done by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and the World Health Organisation (WHO), there are simply too many people in need.

We are impressed with the Yemeni ministry of health staff, who work day and night without pay or protection, exposing themselves and their families to sickness. The dedication is beyond commendable.

To help motivate - or say thank-you - the ICRC gave a modest Eid al-Fitr bonus at the end of Ramadan. But we know it is not enough.

EPA

EPAThis is my third mission to Yemen. I love the country. There is nowhere on earth like this anymore. It is complex and fascinating, the Arabia I once dreamed about visiting.

But this mission to Yemen has been less dream, more nightmare. I think the vacant stares in the eyes of children - and their parents - may well haunt me 10 years from now.

Yemen now suffers three-way tragedy: a population under siege, suffering the violence of war and unable to work or access nutritious food or health care; an economic collapse that has led to a rise in criminality; and now a devastating health crisis.

This all leads to what could be the largest cholera outbreak of our lifetime.

EPA

EPAI have worked with the ICRC for 11 years, but this is the first time I have seen this kind of suffering.

The Yemenis' remaining resilience will be sapped. But even if a miracle materialises and the cholera crisis disappears tomorrow, the ongoing war remains.

The people here will still not find the nutrition they need. And the country will be in much worse shape than before.

The deadly imprint of cholera will continue to grow, and its effects will cripple this fragile, war-weary society far into the future.

Johannes Bruwer is the deputy head of delegation for the International Committee of the Red Cross in Sanaa, Yemen.