Irina Karamanos and the first ladies forging their own path

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBeing a spouse to a Latin American leader used to mean playing a visible and powerful part in your husband's career. But not anymore.

As many of the world's most populous countries head to the polls this year, the role of women in politics is transforming at pace in many places.

In Latin America, all eyes will be on Mexico - the region's second-largest democracy could get its first female president.

The two leading candidates are both women, with Claudia Sheinbaum currently at the head of the race.

But the influential non-elected role of the first lady is also changing across the region - not least because Mexico may get a first man instead.

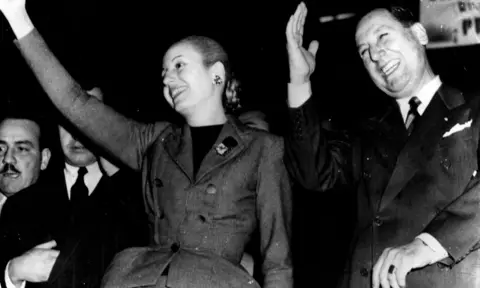

The office has changed since the days of one of the world's most famous first ladies, Eva Perón. The wife of the Argentine president 75 years ago was one of the most influential political voices in Argentine history.

In recent years, women have been pushing back at the role for a number of reasons.

Some believe it is unfair they should ascend to such a powerful, unelected role while others object to the expectation that they sacrifice their own successful careers for the sake of their husband's.

One of the most prominent figures to question the job is Beatriz Gutiérrez Müller, the wife of Mexico's current president, who called it elitist.

Alamy

Alamy"We are all women, we all do something important," she said, adding that there were no "second" women or men.

Ms Gutiérrez Müller advised a fellow first lady, Chilean Irina Karamanos, after her then boyfriend, Gabriel Boric, became Chile's youngest president in 2022 at the age of 35.

A political leader in her own right and a feminist, Ms Karamanos found herself having to take on a job that she felt went against her principles.

"When the campaign ended, I obviously started thinking, OK, what's my role?" she told the BBC last year.

The presidential system in both Latin America and the US means the partner plays a visible part in the country's leadership. Dolley Madison, wife of the fourth US president, is credited with helping to define the role in the early 19th Century well before the term was first used.

Alamy

AlamyMs Karamanos was given an office inside the presidential palace, her own team, as well as a set of six foundations to preside over. And that was when her doubts began to grow. She started speaking to lawyers, trying to get an understanding of what was expected of her.

"Why me? Why the partner of the president?" she questioned. "Why should she have that much power? Nobody elected her."

In a country that only emerged from military dictatorship some 30 years ago, Ms Karamanos said it felt very undemocratic for someone like her to suddenly be given all this power. But she took the job.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I decided that feminist action was more important than feminist image because a lot of criticism came along - that I as a feminist shouldn't be entering the most conservative place in government," she said.

"But I was like, look, if you want to actually change something, you have to do it from the inside."

Irina Karamanos eventually talked herself out of the job - she transferred the foundations to those she felt were more qualified to run them, closed the office down and her team resigned. She stopped working as the first lady in December 2022.

She is no longer with the president but she has left a legacy in Chile - there will be no office for the first lady - or gentleman - for any future presidential partner. But she came in for some criticism over the changes she made.

She says she has no regrets, because democratic institutions need to be legitimised. "One way is to revise all the parts and not keep some parts going, if you notice they are not as legitimate as they deserve to be."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWomen like Ms Karamanos are increasingly questioning the role which has diminished its importance, says Dr Esperanza Palma, professor of sociology at the Autonomous Metropolitan University in Mexico City.

"Political participation among women has changed a lot in most countries in Latin America.

"Yes, there are still wives of presidents but they are professional women, or feminists who have progressive values and so they don't play that traditional role any more. The figure of the first lady is now a bit ridiculous."

In Brazil, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva's wife Janja has also been trying to shape her role since he became president in January last year. Contrary to Ms Karamanos, she threw herself into the role.

"Since the campaign I've said I wanted to reshape this role of first lady - the wife who hosts charity teas and visits philanthropic institutions, that's not my profile," she told the BBC.

Getty Images

Getty Images"Mine is the role of articulator, who talks about public policy. We can be in different spaces and talking to different audiences when necessary."

When she paid a solo visit to communities affected by floods in Rio Grande do Sul, critics accused her of overstepping the mark - she was not elected, they said.

She was shocked that in the 21st Century people still argued about what a first lady could do, she told the BBC. "[Lula] gives me total autonomy so I can do what I do. This line of hierarchy doesn't exist between me and my husband."

For Janja Lula da Silva, it is about choice.

"It's about breaking out of the box that first ladies are always forced into," she says. "It's about not having that box. She can do whatever she wants to."

For Irina Karamanos, stepping down was significant in conservative Chile, a country used to tradition within its institutions.

"It's culturally important because you're constantly giving an image of a very traditional, heteronormative role - or reproducing an image of the most conservative version of a woman."

It is not without struggles - this region is known for its machisimo, after all.

But the last decade has witnessed a powerful feminist movement that both women have been a prominent part of. And they are ripping up the rulebook in very different ways.

Katy Watson is now BBC Sydney correspondent