Antigua and Barbuda's youth orchestra plays to inspire

Gemma Hazelwood

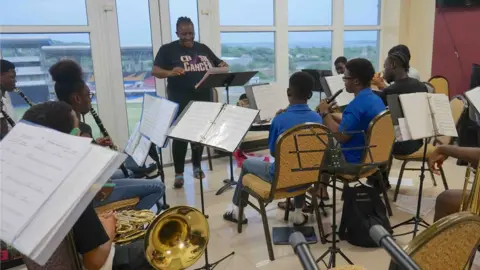

Gemma HazelwoodAs far as rehearsals rooms go, it is not ideal. But this modest office overlooking the Sir Vivian Richards stadium - complete with statue of the mighty cricketer himself - is a reminder at least that small nations are capable of lofty achievements.

The questionable acoustics do little to quell the enthusiasm of the young musicians who comprise Antigua and Barbuda's Youth Symphony Orchestra.

Before the orchestra's formation seven years ago, most of these teenagers had never picked up a classical instrument, much less grappled with the tricky compositions of Tchaikovsky.

Today they are hard at work practising one of Dvorak's Slavonic Dances ahead of a highly anticipated performance in London later this month alongside the Royal Philharmonic.

Orlando Gordon, 17, says learning the trombone might never have crossed his mind, had he not seen one of the orchestra's early performances and been inspired to join.

Gemma Handy

Gemma HandyOn that particular occasion, the Kanneh-Mason family - who have Antiguan heritage and have been integral in helping the orchestra get off the ground - were among the ensemble on stage.

"I was blown away by Sheku's sound specifically," Orlando says of the young cellist who won the BBC Young Musician competition in 2016. "I said 'I have to be on that stage'."

Despite having no musical experience, Orlando, then 13, was welcomed into the orchestra and invited to pick an instrument.

"I chose the trombone, not knowing what it was. My friend told me to just blow into it and hear the sound come out," he says, letting out a belly laugh as he imitates the far from melodic noise it made.

Orlando quickly became adept and soon had a circle of new friends too.

"The orchestra is a place where you can have genuine teenage fun," he says. "Even if you don't know how to play or read music, they will take the time to teach you and it's all for free."

Born to a mechanic father and a mother who works in tourism, Orlando is the first musician in his family.

Gemma Handy

Gemma HandyWhile his peers are out socialising, Orlando can usually be found at home composing music and is now writing full orchestra pieces, a hobby given impetus during pandemic lockdowns.

"My parents are really proud of me," he says. "They didn't expect it at all as they're not musical people."

In addition to giving him an outlet for self-expression, mastering complex harmonies has spawned success in Orlando's studies too. Having to read and listen carefully translated to better grades in maths, he adds.

For 15-year-old violinist Emily James, sight-reading the notes and memorising techniques have also translated to increased ability in the classroom.

Gemma Handy

Gemma HandyIn a country where most youngsters her age are listening to Caribbean soca and dancehall, Emily is something of an anomaly. Even before joining the orchestra in 2019, she would tune in to classical music on YouTube to help her study.

The violin is notoriously difficult to learn and Emily admits her first attempts were somewhat "squeaky".

"I have to practise a lot, because some of those pieces are really difficult. I think it will take many years to really master it," she tells the BBC.

But the feeling of being on stage, performing with her friends, immersed in the musical alchemy they create, is worth the effort.

For the orchestra's founders, Emily and Orlando are precisely the kind of success stories they had hoped for.

Discovering Sheku Kanneh-Mason's Antiguan links seven years ago galvanised the country's High Commissioner to the UK, Karen Mae-Hill, into action.

Sheku and his family were invited to the island to perform and assess local appetite for setting up an orchestra.

Organisers were overwhelmed by the reception and began to put plans in place.

Gemma Handy

Gemma HandyA dream, of course, is one thing. Making it a reality - on a tiny island of 100,000 people - is another entirely.

"We didn't have the structure, our technical ability was limited and finding people to teach was a challenge," recalls Claudine Benjamin, the orchestra's chief operating officer.

The Kanneh-Masons were integral in helping form a transatlantic network of goodwill.

"People saw value in what we wanted to do, which was impact the lives of young people through music," Claudine explains.

Partnerships were formed with various charitable bodies - such as The Commonwealth Resounds, Luthiers Without Borders and The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music (ABRSM) - which supplied instruments, tutors and mentors, as well as invaluable training and support.

"The generosity over the years has been phenomenal - as has the dedication we are seeing from the young people," Claudine says.

Accessibility for all is at the core of the orchestra's ethos. The only requirement to join is self-discipline. Youngsters with no transport are picked up from home so they can attend practice.

Gemma Handy

Gemma HandyThese days, international mentors are working online with the group's student teachers to slowly reduce reliance on overseas help.

Orlando thinks that one day, Antigua and Barbuda could have its own conservatoire, enhancing the nation's touristic offerings far beyond the beaches.

Claudine smiles as she speaks of the doors slowly being opened to the country's young people.

On 15 October, the orchestra will join the Royal Philharmonic on stage at Duke's Hall in Marylebone.

"That's something they might see on television, never thinking an opportunity like that would be available to them," Claudine says.

"They can sit on stage with these people, collaborate with them and learn from them."

Claudine is a staunch believer in the talent that rests within the twin isles' borders and hopes to establish an annual music festival one day.

"We don't play to entertain, but to inspire," she says, adding: "We want to be known as a people who can do this. We never want a 'charity clap': we want a wow."