Peru's political crisis: Jaw-dropping twists and turns

Reuters

ReutersGovernments in Peru in recent years have been anything but stable.

The country has seen a series of presidents ousted and a number of ex-presidents sent to prison for crimes committed during their time in office.

In one memorable week in 2020, the country had three presidents in the space of only five days.

But even by Peru's standards, what happened on 7 December and the week which followed was jaw-dropping both because of the speed with which events unfolded and their consequences.

The man who was president is in detention after what the constitutional court said was an attempted coup; his former prime minister has gone underground; and his former running mate is now in power, but it is not clear for how long.

A nationwide state of emergency has now been declared to quell deadly protests in which hundreds were injured.

What happened?

While the crisis had been brewing for a while, the way it came to a head was a shock even to those closest to the man at the centre of it.

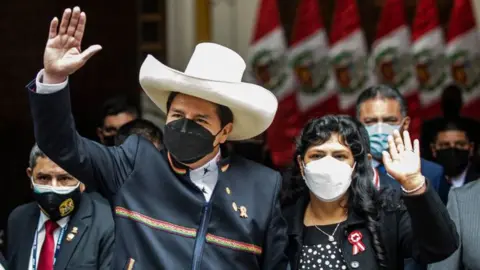

On 7 December, President Pedro Castillo, a 53-year-old former school teacher from a humble rural background who was elected on a wave of frustration with conventional politics in 2021, made a surprise address to the nation.

His hands visibly shaking as he haltingly read from a script, he announced he was dissolving Congress and replacing it with an "exceptional emergency government".

He also declared a nationwide state of emergency. The president said the move was aimed at "re-establishing the rule of law and democracy".

What was the reaction?

The move was met with shock. The head of the constitutional court accused Mr Castillo of launching a coup d'etat.

Many of his ministers, including the defence minister, resigned on the spot and his Vice-President, Dina Boluarte, denounced the dissolution of Congress on Twitter.

The police and the armed forces issued a joint statement saying they backed the constitution.

Congress defied Mr Castillo and called an emergency meeting at which they voted overwhelmingly to impeach him.

What led up to this?

President Pedro Castillo had been facing an impeachment vote in Congress on 7 December before he took to the airwaves.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs two previous attempts to impeach him had failed to get the necessary votes, most commentators and analysts predicted he would survive this attempt to unseat him as well.

After all, two-thirds of members of Congress would have to vote in favour of impeachment for him to be removed from office.

And while Peru's Congress is dominated by parties opposed to Mr Castillo, it is also made up of many small parties which do not often agree.

Add to that that the charge of "moral incapacity" against Mr Castillo was a rather vague one, and it seemed likely that the president would be able to fend off the impeachment attempt.

Why was the president facing impeachment?

Pedro Castillo, 53, has had a rocky presidency from the start. A left-wing former schoolteacher, he was elected by a narrow margin in June 2021, beating his right-wing rival Keiko Fujimori.

With little political experience and lacking the connections and influence of his rival, he faced a hostile Congress which made it extremely hard for him to govern.

His cabinet underwent constant change and during his 17 months in office he had five prime ministers.

His presidency was also overshadowed by allegations of corruption, which he said were part of a "political persecution".

What swayed Mr Castillo?

This is the big question. When Mr Castillo read out his statements, he appeared nervous and no at all sure of himself.

One of his closest advisers told Spanish daily El País that he knew nothing about Mr Castillo's plan to dissolve Congress.

Some think he may have been influenced by Aníbal Torres, who served as his prime minister from February until his resignation on 24 November.

Mr Torres, a lawyer, was present when Mr Castillo announced he was dissolving parliament and also when Mr Castillo was later detained.

Reuters

ReutersThe theory being put forward is that Mr Castillo - whose approval rating with the Peruvian public was low, but higher than that of the even more unpopular Congress - was encouraged to take the drastic step of ruling by decree in the hope that Peruvians would prefer his government of emergency to the elected, but divided, Congress.

Mr Torres is now under investigation along with Mr Castillo for alleged rebellion. In a tweet, he announced he was "going underground". His whereabouts are not currently known.

What did Congress do?

Congress defied President Castillo and brought its impeachment vote forward by a few hours.

Lawmakers quickly and overwhelmingly voted in favour of impeaching the president by 101 in favour, six against and 10 abstentions.

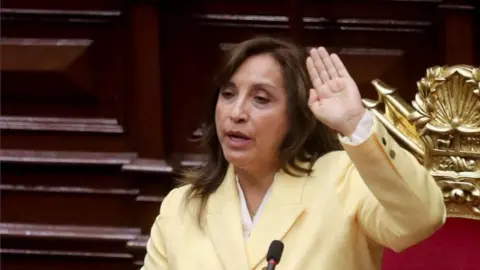

They also summoned Ms Boluarte and swiftly swore her in as the new president.

Reuters

ReutersWhat did Mr Castillo do next?

Mr Castillo and his family left the presidential palace and headed to the Mexican embassy where they planned to ask for political asylum.

But on his way there, his own police bodyguards stopped the car and, on the orders of their superiors, took Mr Castillo to police premises instead.

There, he was detained by the attorney-general. He has since been put in pre-trial detention while he is under investigation for alleged rebellion.

How did Peruvians respond?

Many condemned Mr Castillo's attempt to dissolve Congress and described the move as "autocratic".

They compared it to the 1992 "autogolpe", the Spanish word meaning "self-coup", which is used to describe the actions of President Alberto Fujimori, who successfully dissolved Congress and the judiciary with the backing of the military.

And while there was widespread relief that Mr Castillo had not succeeded, there is also unease about what will happen next.

Discontent with Congress remains pervasive and there have been violent protests in which demonstrators have called for fresh general elections.

Reuters

ReutersSupporters of Mr Castillo have also taken to the streets to demand his release.

What next?

Peru remains deeply mired in a political quagmire. When she was sworn in as president, Dina Boluarte said she would serve out Mr Castillo's term in office, which was due to end in July 2026.

Five days later, on 12 December, Ms Boluarte proposed bringing elections forward by two years to April 2024.

On 14 December, she suggested holding the election even earlier, in December 2023.

Her priority will be to quell the protests which have erupted since she assumed power and on 14 December the defence minister declared a 30-day state of emergency.

However, anger among the supporters of Mr Castillo is likely to escalate further with every protester that is killed in clashes with the security forces.

Meanwhile those who cannot move freely and whose work is affected by the protests are also becoming increasingly impatient.

With discontent growing, President Boluarte is unlikely to be given the space and time to unite the country that she had asked Peruvians to grant her when she was sworn in.