'We gave Venezuelan migrants a licence to dream'

AFP

AFPWhen the Colombian government announced in February that it would grant almost a million undocumented Venezuelan migrants legal status, the move was welcomed as "a historic gesture".

The United Nation's High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi, praised Colombia "for its extraordinary generosity".

Three months on from the announcement, Lucas Gómez, Colombia's presidential adviser on border matters, in an interview with the BBC is urging other countries in the region to follow suit and for the international community to step up financially to make the integration of the Venezuelan migrants a success.

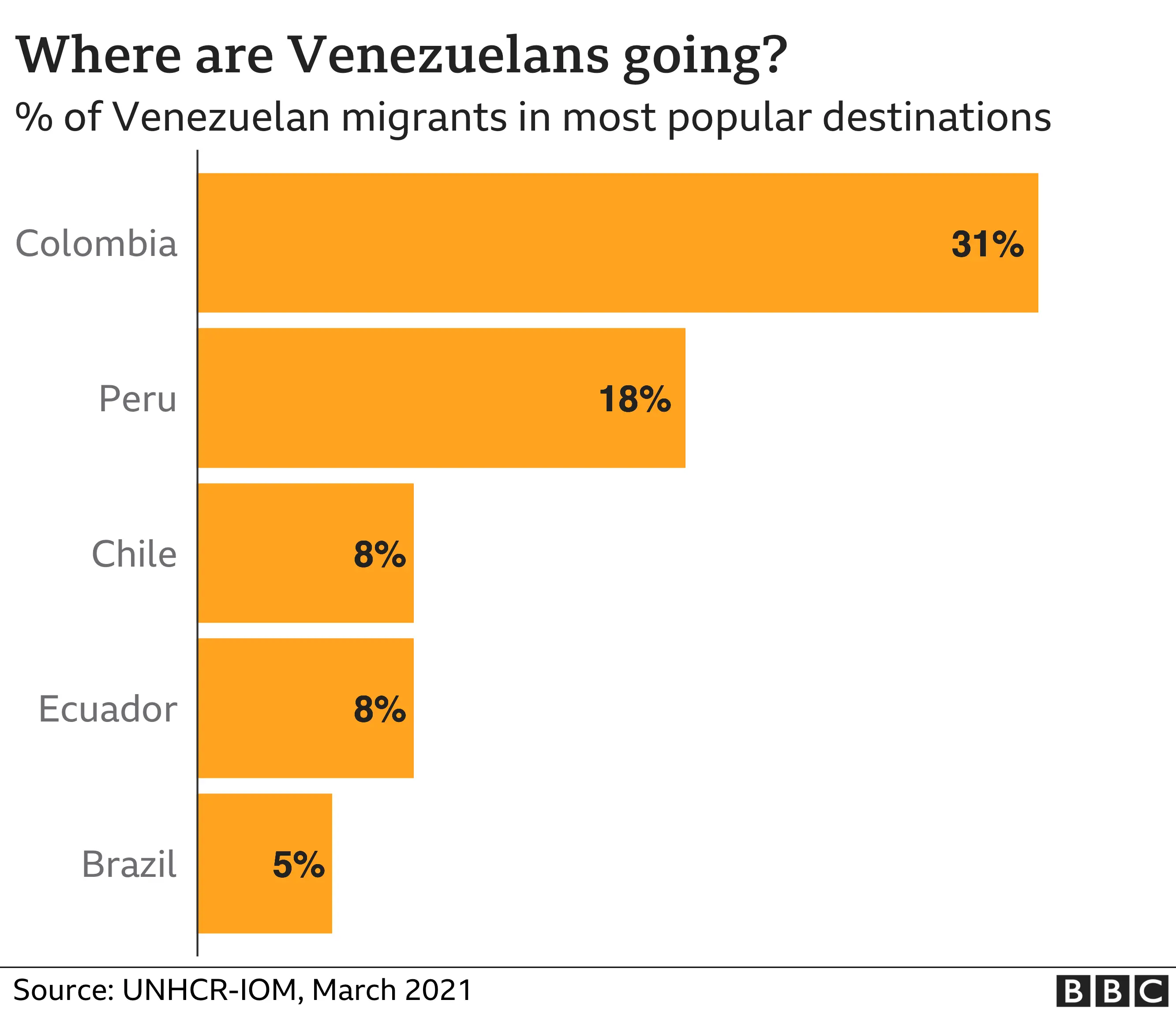

The number of Venezuelans who have left their country in the past five years to escape their homeland's political and economic crisis currently stands at more than 5.6 million.

Read about why Venezuelans are leaving their country

That makes it the second largest migration crisis worldwide.

Almost one third of all of those who leave Venezuela go to neighbouring Colombia.

The country is currently hosting 1.74 million Venezuelan migrants who are intending to stay in Colombia long term. More than half of them are undocumented, meaning they have trouble accessing essential services and getting work.

Most of them have left Venezuela since 2017, when mass anti-government protests swept through Venezuela and an economic crisis started to cause widespread shortages of medicine, fuel and food.

Faced with such a large number of Venezuelan migrants, the Colombian government took the unprecedented step of granting them temporary protected status for 10 years.

The measure applies to Venezuelans who entered Colombia before 31 January 2021 both through official border posts and to those who slipped across without registering.

Joe Raedle

Joe RaedleIt will also be on offer until 1 July 2023 to Venezuelans entering the country through legal channels once the borders - which are currently closed due to the Covid pandemic - re-open. The idea is to encourage future migrants to use the official border crossings and enter through legal channels rather than "trochas", the name given to the paths which criss-cross the 2,200km-long (1,375 miles) frontier.

Colombia's Central Bank predicts that the re-opening of the border will lead to a steep increase in the number of Venezuelans entering the country. It estimates that by the end of 2022 between three and five million could have settled in Colombia.

The government predicts that by granting them temporary protected status, which in turns allows them to find formal work and access social services, the Venezuelans will contribute to Colombia's productivity rather than be a burden.

But in the short term, there are costs involved to integrating such a large influx of migrants, many of whom come with only the belongings they can carry on their backs.

With public health services on their knees in Venezuela, many of the migrants have health problems in need of urgent attention, and hospitals in cities with high numbers of migrants have seen a large influx of patients without the means to pay for their treatment.

Colombia has spent $187.8m (£133.2m) on providing health care for migrants. Colombia's Central Bank expects that figure to quadruple for the period between 2020 and 2022.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith almost half a million migrant children attending public schools, the cost to Colombia's public school system has also been considerable.

The government hopes an international donor conference scheduled for next month will raise funds to cover some of the debts incurred by public hospitals.

But while funds are important, what matters more is to send a signal, says Lucas Gómez, Colombia's presidential adviser on border matters.

Getty Images

Getty Images"We gave Venezuelan migrants a licence to dream," he told the BBC. "By granting them temporary protected status (TPS) for 10 years, they have room to breathe," he says, pointing out that the term is much longer than the 18 months granted by the United States.

For many undocumented Venezuelan migrants, the announcement in February was life-changing as it allows them to work legally without the need for a visa.

But Mr Gómez says that it cannot stop there. "Granting TPS was a crucial first step but we still have a long way to go towards full integration and we'll need support with that."

Mr Gómez hopes an international donors' conference to be hosted by Canada in June will bring some support, especially for a cash transfer system the Colombian government is planning in order to offer struggling Venezuelan migrants a minimum income.

But while Colombia's decision to grant Venezuelan migrants TPS may have been lauded abroad, many Colombians feel the government should be putting the needs of its own people first.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDuring the coronavirus pandemic, unemployment has risen and 3.6 million Colombians were pushed into poverty.

For the past two weeks, tens of thousands of people have taken to the streets to demand that the government do more to reduce high levels of inequality.

Mr Gómez insists that the TPS is a win-win for Colombia as it will allow migrants to work legally and contribute to Colombia's economy but he acknowledges that closing the gap between the haves and have-nots - be they Colombians or newcomers - will be a challenge.

But above all what he wants the international community to do is to send a message that decisions like the one Colombia took to grant TPS to more than a million migrants should not only be applauded but also be supported financially.

"We're hoping that it will create a domino effect and that other countries like Ecuador, Peru and Chile will follow in our footsteps."

"What we can't allow to happen is for Colombia to take a decision like this and for it to go wrong, then no other country will follow suit."