They are killing our forest, Brazilian tribe warns

BBC

BBCBrazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has asked for $1bn (£720m) a year in foreign aid to reduce illegal deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. But under Mr Bolsonaro deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has soared, jeopardising the livelihoods of some of the world's most vulnerable indigenous communities.

Our chief environment correspondent, Justin Rowlatt, has been trying to find out what this has meant for an Amazon tribe he first met back in 2010.

I felt like Mr Bean, the rubber-faced TV character played by Rowan Atkinson, when I first visited the Awa people over a decade ago.

I had expected a yawning cultural chasm would make connecting with them difficult. After all, some of the older tribespeople had grown up in the Amazon rainforest without ever having contact with the outside world.

But it quickly became clear that I was the real curiosity.

The Awa found my bumbling incomprehension about the ways of the jungle hilarious. I squealed when I rested against a spiky tree, tripped over the roots on the jungle path and gagged when they offered me a lightly charred and faintly rotten monkey to eat.

Each mishap prompted a new gale of laughter from my hosts. It was clear my visit was a source of great entertainment for the Awa.

They remain good natured despite the plight the community faces. The conservation charity Survival International has called the Awa the "most threatened tribe on earth".

When I visited in 2010 my best friend in the community, Pirai, told me sometimes they could hear chainsaws in the rainforest near their village.

The Awa are some of the last people on Earth who still try to live as traditional hunter-gatherers but that has been becoming increasingly difficult.

They live in a 289,000-acre forest reserve in the poverty stricken eastern Amazonian state of Maranhão. For decades, loggers and farmers have been invading their ancestral lands and clearing the forests.

And two years ago the threat to the Awa got even greater.

A right-wing ex-army officer, Jair Bolsonaro, became the president of Brazil.

EPA

EPAHe argued that poverty was the biggest threat to the Amazon and said that he believed the Amazon needed to be "developed" as part of the modernisation of Brazil.

The president also claimed that indigenous people did not want to live like "cavemen" and has encouraged mining and agriculture in the world's largest rainforest.

And the effects can be seen in the latest figures for deforestation, environmentalists maintain.

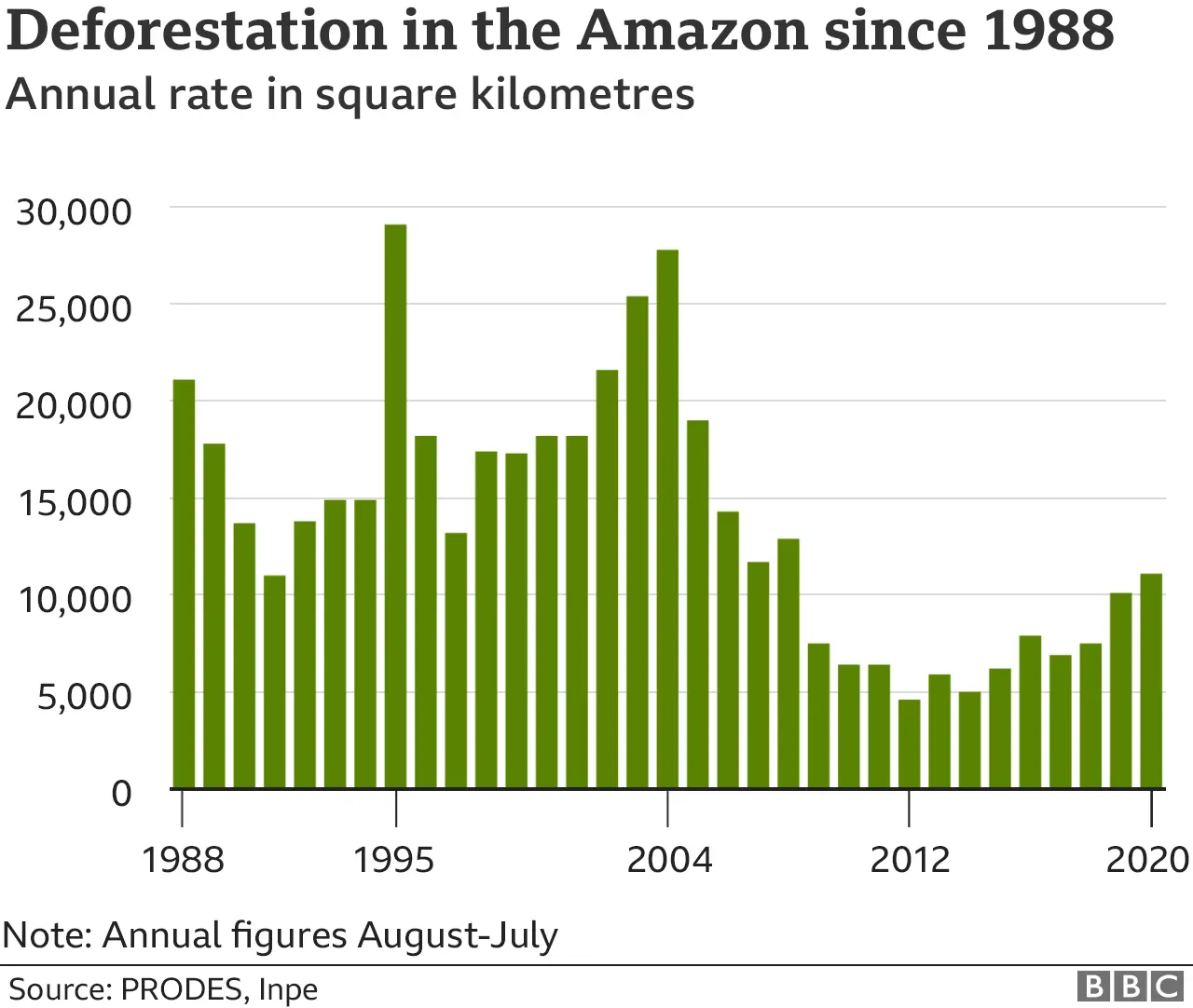

Between August 2019 and July 2020, 11,088 sq km (4,281 sq miles) of rainforest were cleared, according to Brazil's space agency (Inpe). It is the highest rate of deforestation in the Amazon since 2008.

Last week, Mr Bolsonaro said he would stop illegal deforestation by 2030, but he also said that the world would need to pay Brazil $1bn (£720m) of foreign aid a year to help fund the effort.

The environmental police

In 2014, four years after my first visit to the Awa, I got an invitation that proved that the rainforest and the people who live in it can be protected.

I had been invited to witness the culmination of a Brazilian government effort to stop the destruction of the Amazon.

I will never forget watching Pirai and his friend Hamo step nervously into a helicopter for the first time.

They were being flown by the environmental police to see the results of Operation Awa, an unprecedented attempt to clear the Awa's territory of the invaders who were destroying their forest and setting up farms on their land.

Read Justin's previous reports about the Awa:

The effort saw the Brazilian army, air force and military police working alongside the country's environmental protection service in a mission co-ordinated by the indigenous people's agency, Funai.

Their camp on the edge of the Awa reserve was like a forward military base in Afghanistan. It was crawling with heavily armed soldiers and equipment.

The farmers were served with notice to leave and were offered land elsewhere in the state if they did so.

I remember one farming family loading everything they owned onto a truck and I watched as it rumbled away to their new life, leaving a cloud of red Amazon dust in its wake.

They had even stripped the tiles from the roof of the farm they had lived in for 18 years.

The truck with a hand of iron

But the most memorable moment was when Pirai and his friend Hamo landed near the edge of the Awa's reserve and watched as a bulldozer razed the last of the farmers' homes.

"They have a truck with a hand of iron that destroys everything," they told their fellow Awa when they got back to their village.

Operation Awa came at the end of an Amazon-wide effort to reduce deforestation that had begun a decade earlier.

It saw the role of the environmental police force enhanced.

The force was provided with a small fleet of helicopters and new vehicles and the government ordered it should be protected by the police and army. The environmental police was also given authorisation to destroy the equipment of anyone found illegally razing the forest.

During one raid I attended, environmental officers opened fire on a team of loggers, on another I watched as they smashed an illegal saw mill and set the wreckage on fire.

A blacklist of farmers and loggers involved in illegal activities was set up which made it harder for them to sell their produce or get loans.

The effect of these policies was profound. By 2012 deforestation had fallen to the lowest level since records began in 1988.

It was, I wrote at the time, "that rare thing, an environmental battle that is actually being won".

Anarchy in the Amazon

Sadly, that is far from true now.

I knew that the government's focus on stopping deforestation had slipped, but this was exceptional even by Brazilian standards.

Then, in April last year, as the coronavirus raged through Brazil, Brazil's environment minister, Ricardo Salles, addressed a cabinet meeting hosted by President Bolsonaro.

"We have the chance at this moment, when the press attention is almost exclusively on Covid and not on the Amazon", said Mr Salles. "Whilst things are quiet, let's do this all at once and change all the rules," he continued.

He later said that he actually meant to say "simplify" the rules. But a senior officer in Brazil's environmental police force says environmental protection has been steadily rolled back in the Amazon under the Bolsonaro administration.

Funding for the environmental police has been dramatically reduced and President Bolsonaro has also said that the environmental police should no longer destroy the equipment used for deforestation.

The officer said his teams could no longer rely on support from the local police.

Police under attack

He believes farmers, loggers and miners who can profit from destroying the forest have been emboldened because they feel they have the support of the government.

"The job is getting more and more risky, it has become a guerrilla warfare," he told me.

Footage shared online shows environmental police officers being attacked by mobs and loggers building road blocks to keep them out of the forest.

"In places where we didn't have incidents in the past, now loggers, prospectors, squatters are rioting", the officer said, shaking his head in exasperation.

The leading Brazilian environmental NGO Observatório do Clima argues the statistics speak for themselves.

The Brazilian government denies it is deliberately undermining environmental protection. It told the BBC it takes protecting the Amazon very seriously.

It acknowledged that local officials had sometimes withdrawn police protection for environmental officers but said this was not official policy.

And it said the rules on burning the equipment loggers and farmers use had not changed.

A message from the Awa

I was desperate to know how the Awa were getting on. After much phoning around we managed to get a message through to them.

It seemed like an eternity before we finally got a reply in January. It was a recorded message from Pirai.

I could hear the jungle birds in the background but his words were full of foreboding. "The chainsaw is still buzzing just like the days you came here", he told me. "The loggers are coming back".

He had managed to send some photos of the community. I recognised many of the faces. They did not look like the happy people I had spent time with a decade earlier. Their expressions were serious.

"Loggers, farmers, hunters, invaders...they are all coming back," Pirai continued. "They are killing all our forest."