'Not just numbers': The women disappearing in Peru

Florence Goupil

Florence GoupilCinthia Estrada Bolívar remembers the day her family received a phone call from the community kitchen which her 29-year-old sister Marleny co-ordinated in the Peruvian capital, Lima.

It was 16 July and Marleny had not turned up to cook for the poor, something which was completely out of character for the mother-of-two.

Cinthia, her parents and another sister went to Marleny's home in a poor neighbourhood of Lima to look for her. They were greeted by Marleny's ex-husband.

Florence Goupil

Florence GoupilCalmly, he told them that Marleny had just left. Cinthia remembers being bothered by the fact that he did not seem upset by the fact that the mother of his two children had disappeared.

She was also worried as Marleny had in the past reported her ex-husband for being violent against her and her son.

The following day, still without any news from Marleny, the family went to the police to report her missing.

Florence Goupil

Florence Goupil"We had confidence in the authorities," Cinthia recalls. But she says that that confidence was soon shattered as the family got the impression that the police were not taking the case seriously.

Officers told the family to stay away from Marleny's home as the investigation was now in the hands of the police.

In August, Marleny's ex-husband left Lima with their two children, aged three and eight. He has not been seen or heard of since.

Weeks later, Cinthia dreamt that her sister was at home, dead. She managed to convince the police to accompany the family to Marleny's house.

Florence Goupil

Florence GoupilWhile the police searched one part of the house with sniffer dogs, Cinthia and her father searched the bedroom.

"The room looked different, there was something different about the floor," Cinthia recalls.

She and her father took up the floorboards and started digging. While the shovel slid into the ground easily, they found nothing at first.

"My intuition told me that Marleny was down there," Cinthia says. A horrible smell coming from the hole seemed to prove her right.

The police took over the search and asked the family to leave the room. Eventually, they found Marleny's body buried a metre and a half down. Cinthia is convinced that her sister's body could have been located earlier.

An arrest warrant has been issued for Marleny's ex-husband on suspicion of murder but his whereabouts are unknown.

Florence Goupil

Florence GoupilCinthia wants justice for her murdered sister. She also thinks her family could have been spared weeks of anguish and that they would stand a better chance of tracing her missing niece and nephew if only the police had acted faster.

Not all disappearances end as tragically as Marleny's but even the families whose loved ones are eventually found alive live through anguished times until their return.

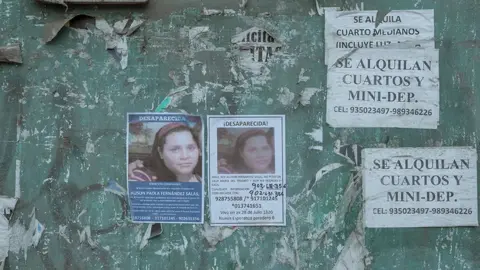

Thirty-year-old Alison Paola Fernández has gone missing twice. With a mental age of just 12, Alison first disappeared after being raped by a neighbour and giving birth to his child.

Florence Goupil

Florence GoupilHer family found her six months later living in another part of Lima with an old man. It is not clear how she came to be living with the man and whether she was staying with him out of her own free will.

In August 2020, she disappeared again, much to her family's despair.

Florence Goupil

Florence GoupilHer sister-in-law, Jessica Quesada Bocanegra, reported her missing. She filed a missing person's report with the police but says that she does not know if they took any action.

Florence Goupil

Florence Goupil"They just called the other day to ask if Alison had turned up, I don't think they did anything to find her," Ms Quesada says.

Thousands of people are reported missing in Peru each year. Between January and September 2020, 13,070 missing persons reports were filed. According to official police figures, more than half of those were underage.

Florence Goupil

Florence GoupilThe women's rights representative at the Ombudsman's Office, Eliana Revollar Añaños, says she thinks that the majority of children who go missing are fleeing rape, violence or sexual abuse.

Women make up 63% of those reported missing and with domestic violence on the rise during the months of Covid lockdown, women's rights activists fear many of those will have have fled abuse or - even worse - some may have come to harm.

Between March and July - months during which Peru was under strict lockdown - there were 11,000 instances of violence against women, according to the Ministry of Women. Almost 30% of the victims were underage.

But a lack of reliable data on disappearances makes any analysis or follow-up difficult. "We do not know how many of them have been found and how many are still missing," Ms Revollar Añaños says.

"Minors who run away are a sign that we have failed as society," she adds.

Katherine Soto Torres from the organisation Mujeres Desaparecidas Perú (Missing Women Peru) thinks the authorities are to blame for focusing on figures too much. "Missing women are not just numbers, they are human beings," she says.

"The state should provide answers to the families - it's as if their daughter or sister had never existed," she says of the lack of follow-up by the authorities.

Ms Revollar Añaños thinks in some instances quicker action by the police could mean the difference between life and death. "We have 19 women who were reported missing and were later found dead. If they had been searched for in a more timely manner, their lives could probably have been saved," she says.

Florence Goupil

Florence GoupilElsa Huallpacusi is an adviser at Peru's interior ministry, the state authority in charge of the police. She says that all the missing person cases have been given due attention.

She says a lack of co-operation on the part of the relatives bogs down the investigations. "They report a family member missing, then they find the person but don't tell the authorities. If they remembered to tell us when a person has returned, it would help," she argues.

Ms Soto Torres of the Missing Women organisation says families are routinely blamed for the disappearances, and victim-blaming is not uncommon either. "They argue that the woman probably did something to make her partner jealous, prompting him to do something to her."

Florence Goupil

Florence GoupilOne thing women's rights activists and officials agree on is that a lack of data has been hampering the search for the missing.

Last week, a new national search system was launched by President Martín Vizcarra and as part of the system there is now a national registry in which information on missing persons is collated and centrally stored.

Alison, who had disappeared in August, was found in September. People who had seen the photo her sister-in-law had published on Missing Women's Facebook page got in touch to say they had seen her ambling about on the outskirts of Lima.

She is now safely reunited with her family but many other families are continuing to search for their loved ones.

They hold out hope that the new national register will speed up police work and that they, too, will be reunited with those who are missing.

All photos by Florence Goupil and subject to copyright.