Mexico ambush: Mormon families waiting for justice a year on from massacre

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA year ago, three Mormon women and six of their children were massacred on a lonely road in Mexico's Sonora desert. What has happened to the families left behind, and their search for justice?

"We came here to get away from it all. And nobody's ever bothered us."

Kenny Miller speaks in a thick southern American drawl. In a camo trucker hat and thick work boots, he trudges up a dirt path slick with damp clay. On one side are rolling desert hills, thick with mesquite shrubs. On the other, the Sierra Madre mountains push up dark grey clouds.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile born in the USA, Kenny is a permanent resident in Mexico. He lives just a five-hour drive away from the US border. La Mora is more a ranch than a village, with a school, a workshop, cattle sheds and about 30 family homes. A rural idyll.

But as he approaches a black tarpaulin held down with rocks, his expression changes. Twisted metal chunks spill out from the sides.

It is haunting evidence of the tragedy that struck this community. "It's just turned our world upside down, and I don't think it will ever be the same again."

On 4 November 2019, Kenny's daughter-in-law Rhonita Miller - known to her family as Nita - and two other women, Christina Langford and Dawna Ray Langford, set out in convoy on a six-hour drive. They were heading to Colonia LeBaron, another Mormon settlement, and home to many friends and family.

Dawna was going to a wedding in LeBaron, while Rhonita was heading to meet her husband. Christina was visiting her in-laws ahead of a move back to the US. She and her six children were to be reunited with husband Tyler who worked in the oil industry in North Dakota.

Lonely journey

The previous night, at a farewell party for Christina, the women had discussed the road to LeBaron. The journey was a familiar but lonely one. The open dirt road climbs through a narrow mountain pass, before dipping into the plains of Chihuahua.

Getty Images

Getty Images"We talked about how stupid we were as women travelling these roads alone with our kids," Christina's mother Amelia told the BBC.

But she says Christina had laughed it off and said she wasn't afraid.

She left five of her six children with her husband and strapped her baby, Faith, who she was still breastfeeding, into the car seat of her Chevrolet Suburban SUV. Altogether, there were 14 children with the three women.

Reuters/handout

Reuters/handoutRhonita's sister, Adrianna, was on an anniversary trip in Canada with her husband when she first knew something was wrong. A message on a family WhatsApp group simply said: "Please, family. Pray this isn't really happening."

The next message, sent to her husband, read: "Nita's Suburban is on fire and all filled with bullets."

"But they're not in there right?" Adrianna recalls asking her husband.

"Nobody would do that to babies, to a woman and four children. Maybe they just kidnapped them and lit it on fire?"

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe answer came in a phone call 45 minutes later.

"He turned around to me and said: "They're all gone. They're all burned."

Gunmen lying in wait

Kenny Miller's son, Andre, was one of the first on the scene. He heard an explosion, and when he went to investigate, saw several armed men with automatic weapons. They slowly walked away from the scene.

Another family member sent up a drone to check the area, and once Kenny and Andrew could see it was clear, approached the scene.

"That's when we realised [it was Rhonita and her children] in the Suburban and they hadn't got out.

The car was just a twisted, smouldering chunk of metal.

"I never knew it would be a blessing to have a body to say goodbye to. But we never got that here." He breaks down. "There was hardly anything left."

The accounts given by Dawna's children, who survived the attack on their own vehicle, have allowed the police to piece together what happened.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGunmen lying in wait had opened fire on all three vehicles. Rhonita's car, just minutes away from La Mora, was hit in a storm of bullets. Rhonita, eight-month twins Titus and Tiana, Krystal,10 and Howard Jr, 12, were all killed. The attackers then torched the vehicle.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFurther up the road, on the mountain pass, Dawna and two of her sons, Trevor, 11, and Rogan, three, were killed. Dawna's other children, some badly hurt, managed to escape their vehicle. Devin, 13, told his six siblings to hide in bushes while he went back to La Mora on foot to raise the alarm. The 14-mile (22.5km) journey took him six hours.

Christina was found dead close to her white SUV.

But when the first convoy of cars from LeBaron arrived about eight hours later, they found Christina's baby Faith alive, with just a tiny graze to her head.

In the wake of the attack, various theories, some outlandish, circulated. Some alleged that the attack was linked to an ongoing dispute over water rights between the LeBaron family and local farmers. Others said it was a deliberate ploy to embarrass the security minister, Alfonso Durazo, who is from the nearby town of Bavispe.

But the authorities' long-held hypothesis is that the La Linea cartel group, strong in Chihuahua state, had been battling with forces aligned with the Sinaloa cartel. A firefight in the nearby city of Agua Prieta the previous night had left both groups on edge. It's believed that when La Linea lookouts spotted the convoy of blacked-out SUVs rolling across the dirt road towards the mountains, they mistook them for their rivals.

The brutality of the attack, and the dual citizenship of the victims, meant the incident attracted huge international attention.

Hours after the news emerged, the FBI sent agents to help the Mexican police investigation. President Donald Trump issued thinly-veiled warnings to Mexico that cartel violence could lead to military intervention.

But that didn't happen, and the investigation itself has proceeded at a glacial pace. Mexican federal judicial authorities confirmed to the BBC that 12 people have been charged in connection with the attack, although only two of those has been indicted for murder. A trial date is yet to be set.

Polygamous marriages

The community which was attacked has been in this part of Mexico for generations. The story of how their ancestors came from the US to settle here is rooted in the unique nature of their beliefs.

Polygamous marriages - allowing a man to take two or more wives - were once common in the Mormon Church, otherwise known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. But as the Mormon-controlled state of Utah sought to join the union of the United States, the practice became a stumbling block.

So in 1890 Mormon Church President Wilford Woodruff banned new polygamous marriages from taking place.

So-called fundamentalist Mormons began to look outside the US for places to settle. Many crossed the Rio Grande and headed to Mexico. They gained a reputation as hard workers and eager cultivators of the land. Local authorities tolerated their unusual marriages, in light of their economic utility.

Jenny Langford first came to Mexico in 1971, an unlikely candidate for a Mormon pioneer. She was a 23-year-old Welshwoman, who had travelled to the US to work abroad for a year, and met American Mormon Dan Langford in Las Vegas.

Langford family handout

Langford family handout"When I was a little girl, I used to always kind of dream about living on a farm and having lots of children," Jenny says. "I wouldn't dream in a million years I'd end up in Mexico."

When she and Dan arrived in La Mora, the only building was a small brick house owned by Dan's father.

"We didn't have electricity in those days. It was very hard.

"But we lived a natural life in every sense. We grew our own food. We didn't want to be a part of the mainstream. I guess you might say we were a little bit rebellious."

Dan and his brothers built workshops, a cattle shed and eventually, a school. Jenny gave birth to six boys and three girls, home schooling them all.

And then the family expanded further. After about 10 years, a newcomer arrived. Amelia was a tall, striking American woman, almost 20 years younger than Jenny.

Langford family handout

Langford family handout"As soon as I saw Amelia I knew she would be Dan's wife one day," says Jenny. "And then we were married."

Polygamy did not come easily to Jenny.

"But the more I studied, I felt that was what God wanted me to do. We believe that if it was right then, it's right now," she says.

Between them, Jenny and Amelia now have 102 descendants. Jenny, a trained nurse, delivered almost all of them.

"We have a baby shower for every first child and every 12th," Jenny says, laughing as she serves pozole, a traditional Mexican hominy stew. "When God said 'Go forth and multiply', we took him at his word," Jenny says.

"Her children were my children. My children were her children," she adds of Amelia. "If ever I wanted to go on a trip Amelia was here with the children, and vice versa. It worked for us, it really did."

The children love the freedom La Mora offers. "We can do whatever we want here" says Steven, Jenny's 13-year-old grandson, as he milks a cow five times his size. "We can fish and swim, and ride motorbikes and quad bikes".

"There's no police or nothing," he adds with a smile.

Past violence at Colonia LeBaron

If La Mora is the rural idyll, then Colonia LeBaron - the ranch Christina, Rhonita and Dawna were trying to reach - is widely seen as the power centre of Mexico's fundamentalist Mormons.

Here, pecans are grown in vast orchards to be exported all over the world, and the men unwind with a trip to the shooting range or the local tavern. It's closer to Texas, in both a literal and metaphorical sense.

Rhonita Miller's uncle, Julian LeBaron, is one of its Mormon leaders. He knows all too well the dangers the cartels pose to their way of life.

In 2009, Julian's brother Eric, then 16, was kidnapped by local cartel members, who demanded $1m in ransom. The LeBaron community refused to pay and thereby legitimise the cartels. Instead, they organised a protest movement, SOS Chihuahua, to shame the cartels into releasing Eric.

Benjamin LeBaron, Julian's older brother, emerged as the spokesman for the movement, giving interviews in fluent Spanish and successfully lobbying the local governor for a meeting.

After weeks of relentless pressure, Eric was released unharmed, and the LeBarons became heroes in Mexico for their refusal to cave in to the cartels. But Benjamin knew that his stand would come at a price

Two months later, 15 armed men broke down Benjamin's door. They bundled Benjamin, his brother-in-law, and his neighbour, Luis Widmar, into a waiting car.

"They took them four miles down the road, knelt them down, and shot them, four times each, in the back of the head," says Julian.

"My brother was brave. He knew that not paying the ransom for Eric would most likely end up costing him his life."

The attack was a turning point for Colonia LeBaron. Sceptical of the Mexican state's promises to provide security, the LeBarons decided to take matters into their own hands. They set up their own armed patrols and look-out points over the town.

"For 10 years, nobody bothered us. But we never received justice for that crime. In fact, most crimes in Mexico never receive justice," says Julian.

The lack of progress with the La Mora killings has therefore come as no surprise for Julian.

"We don't believe in the authorities anymore. Twelve months on from the attack and they haven't punished the culprits.

"We'll never ever stay quiet. We won't give the authorities the benefit of the doubt."

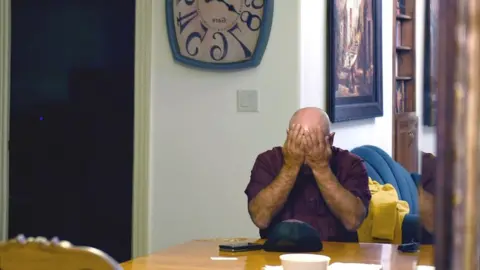

Rhonita's birthday in September was the first the family have had without her.

"We're still suffering a lot, and at the same time trying to continue living," says her sister Adrianna.

"Six months ago I had more hope. The more I get to know about Mexican system, the less I believe that we will get justice.

But Kenny Miller is more conciliatory.

"Our ancestors came here from the USA, and Mexico received them with open arms. So we respect the authorities, those voted in by the people.

"Of course there is cartel violence and that's affected us directly. But we are demanding justice by the correct channels."

Mexico's President, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, has been at pains to reassure the community that his government can handle the situation. He has met with family members several times. During their most recent meeting in October he inaugurated a new National Guard base near the La Mora ranch, as well as announcing a new long-requested highway which will cut the journey time to the US border by several hours, and a monument to the women and children who died.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut despite making reducing violence a central tenet of his campaign, he has presided over rising levels of violence in Mexico. He was elected on a "hugs not bullets" approach to the cartels - promising that by eradicating the conditions for cartel recruitment and growth, their power could be sapped.

The year following the attack, however, looks set to be one of the country's most violent ever.

Competition between cartels has intensified, despite the coronavirus lockdown. And new splinter groups from established cartels have proved willing to use even more violent tactics to get what they want. Civilians have too often been caught in between.

Hope for the future

A year after the massacre, around two-thirds of the ranch's 30 families have left, most of them setting up base in southern Utah.

Jenny and Amelia are among the few inhabitants who have remained. Jenny has a fatalistic view of recent events.

"I've lived here for 48 years. I would never leave. I feel if you're going to die by a bullet, you're going to die by a bullet."

As for the families who have gone, she's optimistic that they will one day return.

"They say the only thing you give your children is roots and wings. And I feel like we've given them the roots and they'll always come back. This is where they belong."