How the pandemic is sending some Brazilians ‘two steps back’

Courtesy Beathriz Samary

Courtesy Beathriz SamaryWhen the coronavirus pandemic spread to Brazil, it dealt a double blow to Beathriz Samary.

In early March, the 21-year-old fell ill with a high fever, body aches and shortness of breath. While she was not able to get access to a coronavirus test, she suspects that what knocked her out for a month was Covid-19. "I was so ill, I couldn't even lift myself up," she recalls.

But the financial impact she suffered was just as hard. Ms Samary, who was earning most of her income from working as a manicurist, was no longer able to go to clients' homes. She and her partner were surviving on a "cesta basica", food parcels donated by a local charity in the Salsa e Merengue neighbourhood they call home.

"What saved us during that time were those food parcels," she says.

Even after she recovered, work was hard to come by. Ms Samary applied for emergency aid - a measure the government approved in April - but it took weeks to arrive. She and her partner fell behind on rent and their internet was cut off. "There was no money, not even for the basics."

Moving up

Before the pandemic, Ms Samary was among the millions of Brazilians who had been climbing out of poverty since the turn of the century.

She grew up in the care of her godmother in Complexo da Maré, a sprawling patchwork of favelas in Rio de Janeiro.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe family of eight lived in a modest wooden home. Her godfather sold fruit and eventually found a steady job as a fishmonger.

Ms Samary started working when she was just 11, but was able to get ahead, eventually earning about 3,000 reais ($585; £450) per month - nearly three times the minimum salary in Brazil.

Stories like that of Ms Samary were not uncommon in Brazil in the last two decades, as the country made strides towards alleviating poverty and inequality. A mix of generous social programmes and a flourishing economy - fuelled by a decade-long commodities boom - helped lift some 36 million Brazilians out of extreme poverty between 2003 and 2014, according to official figures released at the time.

The country received high praise for government-run poverty reduction schemes like Bolsa Familia, which guaranteed healthcare to poor families and gave cash transfers to those who sent their children to school.

Unravelling gains

In recent years, some of these gains have unravelled as commodity prices slumped and a crippling recession hit, says Marcelo Côrtes Neri, a researcher and director of the think tank FGV Social. Some 3.4 million Brazilians slid back into extreme poverty between 2014 and 2018, FGV Social's figures suggest.

Now, dealt a further blow by coronavirus, Brazil's most vulnerable may be in for even tougher times ahead.

"We're in the middle of something that we've never seen in Brazil," Mr Neri says.

"We've seen lost decades before," he adds, but says that the country has never before regressed. "And given the prospects for the future...we're going to go back many years."

There are already signs that poverty is deepening. In the beginning of 2020, the average income of the poorest half of the population dropped 7.7%. Inequality - after starting to decline in late 2019 for the first time in four-and-a-half years - began widening again this year.

"Those who are suffering the most are those who have precarious jobs, the person who is living hand to mouth, who doesn't have a way to pay their rent," says Sonia Rocha, an economist and researcher at the Institute of Labour and Society Studies (IETS).

Searching for opportunities

Before the pandemic, Francisco Flavio Eufrazino spent most of his waking hours running his restaurant in Rocinha, one of Brazil's largest favelas.

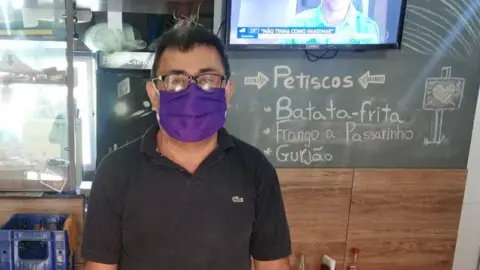

Leonardo Eufrazino

Leonardo EufrazinoThe son of agricultural workers, Mr Eufrazino, was born in Ceará, one of Brazil's poorer states in the north. When he was 18, he moved to Rio de Janeiro in search of better opportunities. The oldest of five sons, he quickly found work and started helping his family back home.

Three years ago, Mr Eufrazino, who is now 56, finally managed to open up his own restaurant, after decades toiling first as a waiter and later as a doorman in a condominium.

"It was going well, it was growing," he says. "We weren't advancing quickly but we were moving forward, one step at a time."

But the pandemic left Mr Eufrazino's restaurant without guests and wiped out most of his income. He had to let his two employees go and could not pay the rent for the premises. The emergency aid and the few takeout lunches he is selling are just about helping him stay afloat.

"It's been really difficult," Mr Eufrazino says. "And the worst is that we don't know when it will end."

Under anaesthesia

The government aid has been key to softening the blow of the pandemic on the poor, Mr Neri says. But the true toll of the crisis will only become clear when the help runs out.

"It's like we've had a big dose of anaesthesia," he says. "But unfortunately, this is not sustainable."

Karina Victoria da Silva was starting out in life when the pandemic hit. Last year, the pedagogy student got a coveted apprenticeship at a private school, caring for toddlers in the nursery.

Yuri Mattos

Yuri MattosShe was preparing to move out of her mother's cramped home in Baixada Fluminense, a sprawling working-class area on the fringes of Rio de Janeiro.

For years, the Bolsa Familia scheme had sustained their family. But Ms Silva was moving in a different direction.

Then the nursery where the 23-year-old was working was closed amid the pandemic and her classes at university were suspended. She was left without income and an uncertain future.

"I was in the middle of moving and the pandemic happened," Ms Silva says. "And then I lost my apprenticeship, I lost everything."

She is surviving thanks to emergency aid from the university and from the government - vital aid that is helping her mother scrape by, too.

For Ms Samary, the pandemic has marked a turning point. With manicures now a luxury for many Brazilians, she found herself with few clients. She got a second job as a telemarketer, "earning less and working a lot more".

She says the uncertainty brought on by coronavirus made her realise she needed stability. And with health professionals in high demand, she has decided to start a course to become a nursing assistant.

Despite all of the setbacks she has suffered, she says she is grateful to have survived Covid and remains optimistic for what lies ahead.

"Everything has gotten better, it's already better now," she says.