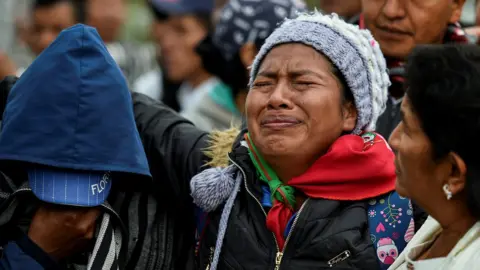

Colombia: How armed gangs are using lockdown to target activists

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn the first day of Colombia's quarantine, Carlota Isabel Salinas was shot dead outside her home.

Ms Salinas played a leading role in a women's organisation in Bolívar province in northern Colombia.

The region had already seen an increase in violence carried out by right-wing paramilitaries in the months before the coronavirus pandemic.

Since the start of the lockdown in late March, 28 activists and human rights defenders across Colombia have been murdered.

The killings are not a new phenomenon: more than 800 activists have been murdered in Colombia since 2016, according to the think tank Indepaz.

But community activists from different parts of Colombia have told the BBC that restrictions on movement imposed to curb the spread of virus mean that they have become even easier targets.

Stuck at home for most of the day and only venturing out to address emerging humanitarian needs in their community has turned them into sitting ducks.

'Scared for my family'

Dolores (whose real name has been withheld for her safety) is one of the leaders of a group of hundreds of mothers who promote women's economic empowerment in Catatumbo, a region in Norte de Santander province - along Colombia's border with Venezuela - which has borne witness to years of extreme violence.

Since the Colombian government signed a peace deal with the left-wing rebel group Farc in 2016, activists like Dolores have been under heightened threats across the country.

While the majority of the Farc rebels laid down their arms, other guerrilla groups, Farc dissidents and paramilitaries continue to clash in zones like Catatumbo.

Now, those groups are exploiting the quarantine to further consolidate power.

You may also be interested in:

In this rural part of Colombia, rival armed groups clash for control of lucrative coca crops and drug transit routes while systematically eliminating activists who challenge their authority.

"I am scared that they might kill my compañeros (comrades), I'm scared for my family," Dolores says.

She and activists like her have received an increasing number of threats from armed groups in recent weeks.

And it does not always stop at threats, either. Last week, one of her activist friends was killed by unidentified armed men in Catatumbo.

'We are the only support they have'

During the quarantine, rights defenders like Dolores have had more work than ever. The women in her community - many of whom are heads of household - have not been able to go out to work and are struggling to feed their families.

Rates of domestic violence have increased and the absence of state institutions in this rural area is now even more keenly felt.

"We know the risks that we run, but right now with this pandemic, [people's needs] have increased," Dolores explains. "For many of them, we are the only support they have left."

She has written letters and posted videos on social media asking the Colombian government for aid for those families but says her pleas have been met with silence and inaction.

'Trapped in the middle'

On the other side of the country, in the mountainous Cauca region, Clemencia Carabalí faces similar threats.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCommunity activists are being killed here almost weekly, and Cauca - where Ms Carabalí campaigns for the rights of women and Afro-Colombians - has been the heart of the killings committed during the lockdown. Ten activists have been murdered here since it began.

"They fight for this territory, it's a bloodbath, and we - as communities and women - are stuck in the middle of it all," Ms Carabalí says.

"We're trapped in the middle but during this quarantine, we have to keep working to protect our people."

Ms Carabalí has received nine death threats since 2016. Dolores, too, has been under constant threat for her work and survived an assassination attempt late last year.

'Very intimidating'

"It's very intimidating, and all we want to do is work as human rights defenders," Ms Carabalí says. "We're at home, and they can follow us much more easily."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIrina Cuesta, a researcher at the Ideas for Peace Foundation (Fundación Ideas para la Paz) says the pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on women rights activists, who now have "triple or quadruple the work" as they struggle to protect not only themselves but also their families and communities.

Their activities expose them to violence at the hands of armed groups who impose their rule in regions where the activists are already "seen as women who shouldn't be participating in the public space".

While overall the number of male activists being killed in Colombia is greater than that of women activists, Ms Cuesta argues that "when you lose a woman leader, you also lose an entire process of political empowerment that was able to break stereotypes to get her to that role".

"It's much more difficult for women to get to these positions of leadership."

Ms Carabalí worries that if people like her stand down, it would be a major setback for their fight for basic rights.

Despite the fear of deadly consequences for her and her family, she says her work is more crucial now than ever before.

"Someone has to do it," she said. "Someone has to raise their voice."