‘Vale ended our lives’: Broken Brumadinho a year after dam collapse

The friendship between Josiana Resende and Natalia de Oliveira is one born out of loss - they got to know each other after the dam collapsed at the Corrego do Feijao mine exactly a year ago, killing both their sisters.

Natalia's sister Lecilda and Josiana's sister Juju were great friends. Lecilda introduced Juju to her husband and she was bridesmaid at the wedding. Now the bond has extended to the surviving sisters.

Natalia and Josiana's friendship is also born out of a shared cause - finding their sisters' bodies. Of the 270 people who died, they and nine others are still missing.

No closure

"We re-live what happened on the 25th every day," says Josiana. "The fact that we can't say goodbye doesn't give us any closure - we can't move on. Time has stood still for us."

This past year has been hard on Juju's dad Geraldo too. He's wearing a T-shirt with a picture of his daughter and her twin boys Geraldo Augusto and Antonio Augusto.

The photo was taken at one of their monthly milestones - Geraldo can't remember if they were eight or nine months at the time but she loved celebrating each and every month. She died shortly afterwards. The boys are the reason the family keeps going.

"When a father cries, it's such a deep pain," Geraldo says between tears. "Those people at Vale ended our lives, we lost the will to live. I have thoughts that I shouldn't talk about. I just want my daughter to come back - but I know it's not going to happen."

Devastated landscape

When the mud and mining waste barrelled through a valley near the town of Brumadinho on 25 January 2019, it wiped out everything in its wake. Now, there's a void in the hillside where the dam used to be. And below it, for nearly 10km (six miles), a lunar landscape of dark mud, with water collecting in the crevasses.

It's rainy season in Brumadinho. The showers last for days at this time of year. But despite the rain, the firefighters keep working in the dam zone.

"It's a massive area, we're talking 10km from where the dam broke to the final part where it met the Rio Paraopeba. And it's a perimeter of 32km," says firefighter Lieutenant Colonel Douglas Constantino. "Now it's rainy season, access is difficult for our people and for our machines but our job is to find those missing 11 victims."

The clean-up

The dam collapse in Brumadinho was one of Brazil's worst environmental disasters. Forests were destroyed and rivers polluted, so it's a big job to relocate the mud to a safer place and return this area to its previous state.

"We've got 2,500 people working here and we're hoping to get rid of all the waste from the dam within five years," says Rogerio Galvao who is in charge of the clean-up operation for Vale, who owned the dam. "But that depends on the progress of firefighters, with their search and recovery efforts."

Vale cannot move any mud without seeking the permission of the firefighters who are looking for the missing.

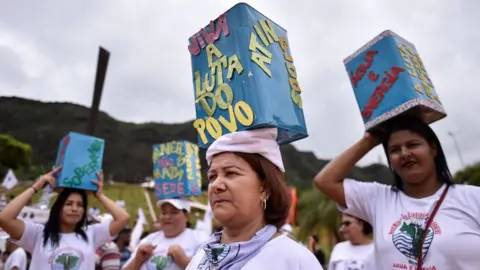

Anger and frustration

There is a great deal of anger towards Vale. The murder and environmental charges handed out to 16 employees, the mining company and its auditor Tuv Sud this week have come as welcome news to many here.

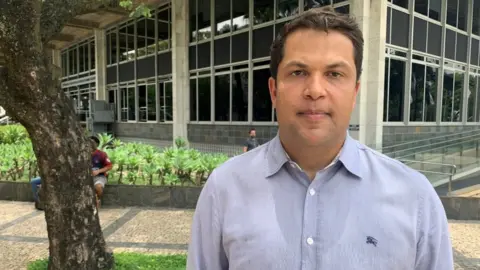

"They knew that this could happen, I'd been saying it for years," says João Vitor Xavier, a politician in the state assembly of Minas Gerais, where Brumadinho is located. "They knew people could die but they prioritised profits."

João Vitor is part of the Energy Commission in Minas Gerais which tried to pass a bill improving mine safety before the disaster. Finally, in the wake of Brumadinho, the bill was passed.

"The legislation that we got through insists on much stricter regulations from now on, companies have to dismantle mines like Brumadinho but that's like messing with a ticking time bomb," he says. "The very act of dismantling them is risky."

Held responsible

When the murder charges were announced by state prosecutors, Vale responded, saying it was "perplexed" by the accusations they intended to kill those who died but insists it is cooperating with the investigation.

"We understand people need to be punished," says Marcelo Klein, the Director of Recovery and Development at Vale. Of the murder charges though, he was more hesitant. "We can't accept that the justices believed we deliberately took actions, or didn't take actions, to intentionally kill people."

The charges have gone right to the very top. The former boss of Vale, Fabio Schvartsman, who stepped down in the wake of the dam collapse, is one of the accused.

Getty Images

Getty Images Getty Images

Getty Images"Prosecutors together with the police looked at the evidence for a year and that evidence pointed to the president's involvement in the crimes that happened that day," says state prosecutor Andressa de Oliveira Lanchotti. "It's not a strategic choice. They are facts and according to Brazilian law, he has to be held responsible for those acts."

A year on from that terrible day, many people are very open about who they blame for what happened - but it does little in helping a community so broken and so hurt, to pick up the pieces.