Mexico under pressure as asylum applications skyrocket

BBC

BBCA recent Trump Administration policy, known as MPP, means immigrants seeking asylum in the United States have to remain in Mexico while they await their court hearings.

In addition, the US has drastically reduced the number of refugees it will accept next year to just 18,000, the lowest in decades.

As Will Grant reports, the two policies are complicating an already overburdened system in Mexico and immigrant shelters are struggling to cope

Behind an innocuous-looking white metal gate in a Mexico City side street, there is a wide, open courtyard surrounded by colourful murals. The images on the walls depict different stages on the migrants' route north to the US.

Yet the immigrants inside this discreet shelter are here because they have abandoned that treacherous trip and chosen to settle in Mexico instead.

The home - called Cafemin - is run by a group of progressive Catholic nuns with help from the United Nations' refugee agency, the UNHCR.

They provide basic training to help their residents find work. In a small kitchen, a volunteer chef is teaching the group to bake cakes and chocolate chip cookies.

Nelcy, a 24-year-old Honduran woman from the Garifuna ethnic group, shows dexterity with a whisk that suggests she already knows how to bake a cake.

Nelcy is heavily pregnant and had been travelling north on the notoriously dangerous freight train, known as La Bestia, with her two daughters.

She says that the land her indigenous group lives on back in Honduras is being sold off to foreign investors by the government.

Her plan was to reach the United States but the legal obstacles recently put up by the Trump administration and the risks to her safety and to those of her children have put her off continuing along the way. Nelcy says she does not want to keep going but cannot turn around either.

"I've got two kids with me," she says, putting down a mixing bowl for a moment to chat.

"The most dangerous thing is to attempt to cross from here into the United States. They kidnap and traffic minors. There's violence. So I think I'm better off here."

She says that if she had been travelling on her own, she might have risked the crossing but at eight months pregnant and with two children under five, she is now looking to put down some roots in the Mexican capital.

Migrants like Nelcy often face a real struggle outside the walls of Cafemin. Mexico can be a tough place to integrate and the numbers of those seeking asylum in the country have risen rapidly.

The United Nations says there has been a more than 3,500% increase in asylum applications in Mexico over the past seven years and as many as 80,000 people are expected to apply this year alone.

This problem is further compounded by a chronic lack of funding for basic asylum and refugee services from the Mexican government led by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, says the Mother Superior of Cafemin, Sister Magdalena Silva.

"We don't expect much, in fact we don't expect anything from this government, a government that's on its knees before its neighbour to the north," she says bluntly.

It is a damning assessment of what she sees as the Mexican government's acquiescence to the Trump administration.

Under the Remain in Mexico (MPP) policy, asylum seekers have to stay in Mexico while their legal cases are processed in the US.

Sister Magdalena says the policy is intended to dissuade would-be migrants from even setting off from their home countries by forcing those who have made it to the US border to wait for months in dangerous border towns.

"Mexico has become a wall of containment. This is a migration policy of containment, of telling them: 'Don't even try. You won't get in.'"

She says that with a bigger workload and no corresponding increase in funding from the Mexican government, civil society groups and Church organisations like hers have to rely on international bodies like the UNHCR for support instead.

Earlier this month, UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi visited Cafemin and saw freshly painted dormitories, new lockers and bunk beds supplied with money from his agency.

Cafemin was able to make some small improvements to its shelter with its limited budget.

But on his trip Mr Grandi also visited other migrant shelters on Mexico's northern and southern borders where the situation is more acute. He urged the Mexican government to increase the budget of its own asylum agency, the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR).

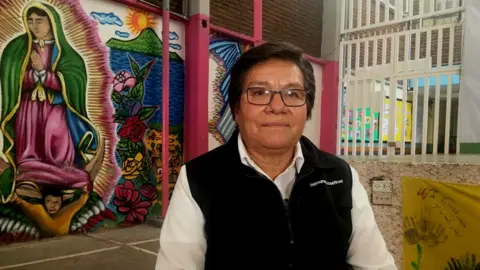

A few days later, in his office in the Mexican capital, the head of COMAR, Andrés Ramírez, said the agency was doing its best but had been struggling to cope with the increased pressures.

"Our problem basically has to do with our resources," he admitted, although he felt that the López Obrador administration did at least appreciate the strain they were currently under.

Mr Ramírez is a natural diplomat and measured his words carefully. So I asked him if he shared Sister Magdalena's fury at the Trump administration's policies, which had added so much to his agency's already insurmountable workload.

"I'm not furious," he laughed, "because if you get mad, then you lose. So you'd better stay calm and try to make the best of the whole thing."

He acknowledges the COMAR offices are particularly stretched along Mexico's northern border where immigrants returned from the US are waiting as more arrive, travelling up from the south.

"I don't think it's a good thing what is being done in the US," he says, "but we need to improve our operational capacity. And I don't gain anything by being furious."