Juan Guaidó: Is there a new cult of personality in Venezuela?

At one point during the noisy rally in Caracas to mark his return to Venezuela, opposition leader Juan Guaidó climbed on to some scaffolding to wave to his supporters.

For a brief moment, it looked almost as though he were going to stage dive into the crowd.

Crowd-surfing would have been entirely inappropriate for a politician, of course, yet strangely in keeping with the mania that has been whipped up around Mr Guaidó. As Venezuela's problems stack up, from hyperinflation to worsening malnutrition, many ordinary people have been looking for someone - anyone - to promise change.

Then on 23 January, Mr Guaidó, the head of the national assembly, who was hitherto barely known outside of Venezuela, declared himself president and immediately took on rock star status.

A recent poll by the Datanalisis polling firm shows him enjoying upwards of 60% popularity and winning a presidential election by more than 75%.

But Venezuela has been here before.

When the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez first burst onto the national stage he cut a messianic figure who was going to save the country's broken politics and economy, and who rode a wave of popularity which, at its height, dwarfed anything seen since.

"It is always a very, very, very fine line," said Mr Guaidó's head of press, Edward Rodriguez. "People start to think that the 'messiah' will solve all their problems. And evidently there is an atmosphere around Guaidó at the moment in which people think he will fix all their problems."

Reuters

ReutersDespite the adoration that opposition supporters are lavishing on Mr Guaidó, his press secretary insists the opposition leader is keeping his feet on the ground.

"He's very aware of that danger and keeps his ego in check," said Mr Rodriguez. "He's conscious that this has been a 20-year long struggle to end the usurpation of power, to create a transitional government and hold free elections."

Supporters of President Nicolás Maduro scoff at the idea of Mr Guaidó taking power.

"How can he just declare himself president like that? I mean, what is that?" said Rosely Riera, as we spoke close to midnight on the roof of her low-income tower block in a pro-Chavez stronghold in Caracas.

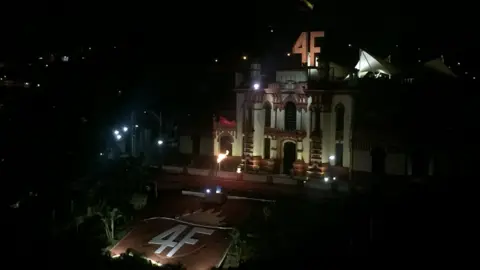

A handful of loyalist Chavistas had gathered on the roof of their building - which overlooks their comandate's final resting place, the Mountain Barracks - to mark the sixth anniversary of Chavez's death.

They were projecting images of Chavez onto a big screen, singing left-wing songs and sharing a little rum. At the stroke of midnight, the music cut out and the crack of gunfire began from neighbouring rooftops in a sign of remembrance.

Ms Riera refused to blame Chavez's hand-picked successor, Nicolás Maduro, for the country's economic chaos. "Nicolás is doing everything humanly possible," she insisted. "It's down to all of us. You can't blame the president because Chavez threw him in at the deep end. But I tell you this: Chavez didn't make a mistake."

AFP/Getty

AFP/GettyChatting over coffee in a nondescript hotel bar in Caracas, Hector Navarro profoundly disagreed. For more than a decade, Mr Navarro was a key member of Chavez's inner circle - minister of everything from education to electrical energy.

Today he has broken completely from Mr Maduro, who he accuses of "co-opting" Hugo Chavez and the Chavista movement.

"In Chavez's name, Nicolás Maduro is destroying socialism, is destroying Chavismo, is destroying progressive ideas in Latin America and around the world." he said. "The CIA [Central Intelligence Agency] themselves couldn't have done a better job!"

Mr Navarro, who has returned to teaching, admitted mistakes were made under Chavez, in particular the cult of personality that was fostered around him.

Yet he said it was borne of necessity - such was the clamour for a strong left-wing leader in 1999. According to Mr Navarro, Mr Maduro is simply a poor impersonator of Chavez.

"Some here would call it a kleptocracy. Conservative estimates say some $300 billion [£230 billion] has disappeared in Venezuela. Others say as much as $450 billion," he said.

"I'd say it's an improvised, right-wing government, which is constantly moving closer to fascism."

AFP/Getty

AFP/GettyHe continued: "Fascism means the denial of others - I'll crush you simply because I can ... And it's a right-wing government because it's prioritising the economic sectors of the right."

Mr Maduro spent part of the anniversary of Chavez's death pinning medals onto military men who had, at his orders, prevented the entrance of humanitarian aid into Venezuela from Colombia. If Mr Maduro is to hold on to power, he will need their help in the weeks to come.

Most Venezuelans are exhausted by the current situation and simply want change. Many are looking to Mr Guaidó. The risk, perhaps, is in pinning all their hopes on one man.