My first week as a BBC Venezuela correspondent

BBC

BBCIf you're a journalist looking for stories, a Bank Holiday Monday isn't usually the most promising start to the week. Unless you live in Caracas.

I've just started as BBC Mundo's Venezuela correspondent, and if this week is anything to go by, I can see I'm going to be extremely busy.

Here in Venezuela, last Monday was the day the government decided all businesses and banks would shut down to get ready to introduce a much-anticipated new currency.

The "sovereign bolivar", as the new money is called, is supposed to tackle the hyperinflation Venezuelans have been enduring for months.

It's effectively a denomination of the old currency - the "strong bolivar" - which has been losing value so rapidly that many smaller denomination notes are totally worthless and the sheer number of bank notes needed to pay for basic goods has become unmanageable.

Most Venezuelans spent Monday wondering and worrying about how the new system would work.

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty ImagesEverybody was keen to get hold of some of the new money, but like almost everything else in Venezuela it wasn't easy.

With the banks closed and digital payment systems out of operation for days, ATMs were the only place to start.

Long queues formed at the few machines that were offering cash.

But withdrawals were limited to 10 new bolivars - that's less than the price of a bottle of water.

Reuters

ReutersOn Tuesday, shops and businesses reopened and Venezuelans began to get to grips with the new money.

Traders and shop owners tried to work out how they should price up their goods.

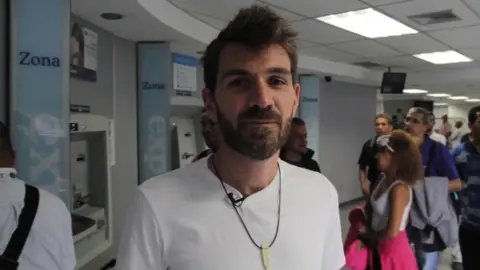

In the banks, baffled customers hovered as staff did their best to clarify how things will work from now on. Despite the chaos, everyone was smiling.

That Venezuelans manage to keep their good mood even in this difficult time sometimes leaves me lost for words. But the conversations I had with customers in the bank showed just how difficult life is for people here.

"I've been here for two hours," one man told me. "You need to be lucky. Some days in this bank they don't have any money at all."

"I just withdrew 10 bolivars from here," another customer told me. "At the clinic where I work the ATM would only give me one."

Everybody was talking about the rampant inflation which has seen prices rising so fast it's almost impossible to keep count.

"Cheese used to cost 600 bolivars a kilo," one woman told me. "Now it costs between seven and nine million. You have to decide fast. If you don't buy something today, it will cost you more tomorrow."

"It's crazy," said another woman. "Everything keeps going up and the government can't control it."

At the end of the day, something else happened to knock the new money off the news headlines.

As people were walking home, sharing stories about whether they'd been lucky enough to get their hands on some new banknotes, a powerful earthquake rocked the city.

There were no fatalities, but the tremors sent residents fleeing from high-rise buildings.

"That went on a bit too long," said an old lady in a dressing-gown standing outside a tower-block.

Reuters

ReutersShe and her neighbours were waiting for the signal that it was safe to go back inside.

Nobody seemed too worried. If anything they were amused by an event, which had distracted them from the tough realities of everyday life.

You never get bored in Caracas.

Between news reports, I have been settling into life in the city - but have already seen many families leaving.

With the country in crisis, Venezuelans have been voting with their feet. Over two million people have packed up their belongings and started a new life outside the country.

Reuters

ReutersAt the end of the week, one conversation in the bank sticks in my mind.

It was with a 17-year-old girl called Yorlen, who told me she wanted to join the exodus and travel to Peru.

"I have a sister there," she said. "I'm currently doing the paperwork to get the passport. I don't see any future here."