Venezuelans confused as Maduro's economic plan starts

Reuters

ReutersA government plan to curb hyperinflation is coming into force in Venezuela amid confusion about how it will work.

From Monday, new banknotes denominated in "sovereign bolivars" are legal tender, with five zeros taken off.

The measures come after the International Monetary Fund predicted that inflation could reach one million per cent this year.

Economists have warned that the new measures could make things worse.

What's happening on Monday?

The move is effectively a redenomination. President Nicolás Maduro is lopping five zeros off the current currency, the "strong bolívar", and giving it its new name.

Eight new banknotes and two new coins will also be launched. The new notes will have a value of 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 500 sovereign bolivars.

Most old bolivar notes will continue to circulate "for a time", Venezuelan Central Bank President Calixto Ortega announced. Only the lowest current notes, worth less than 1,000 strong bolivars, will be phased out straight away,

How will this affect prices?

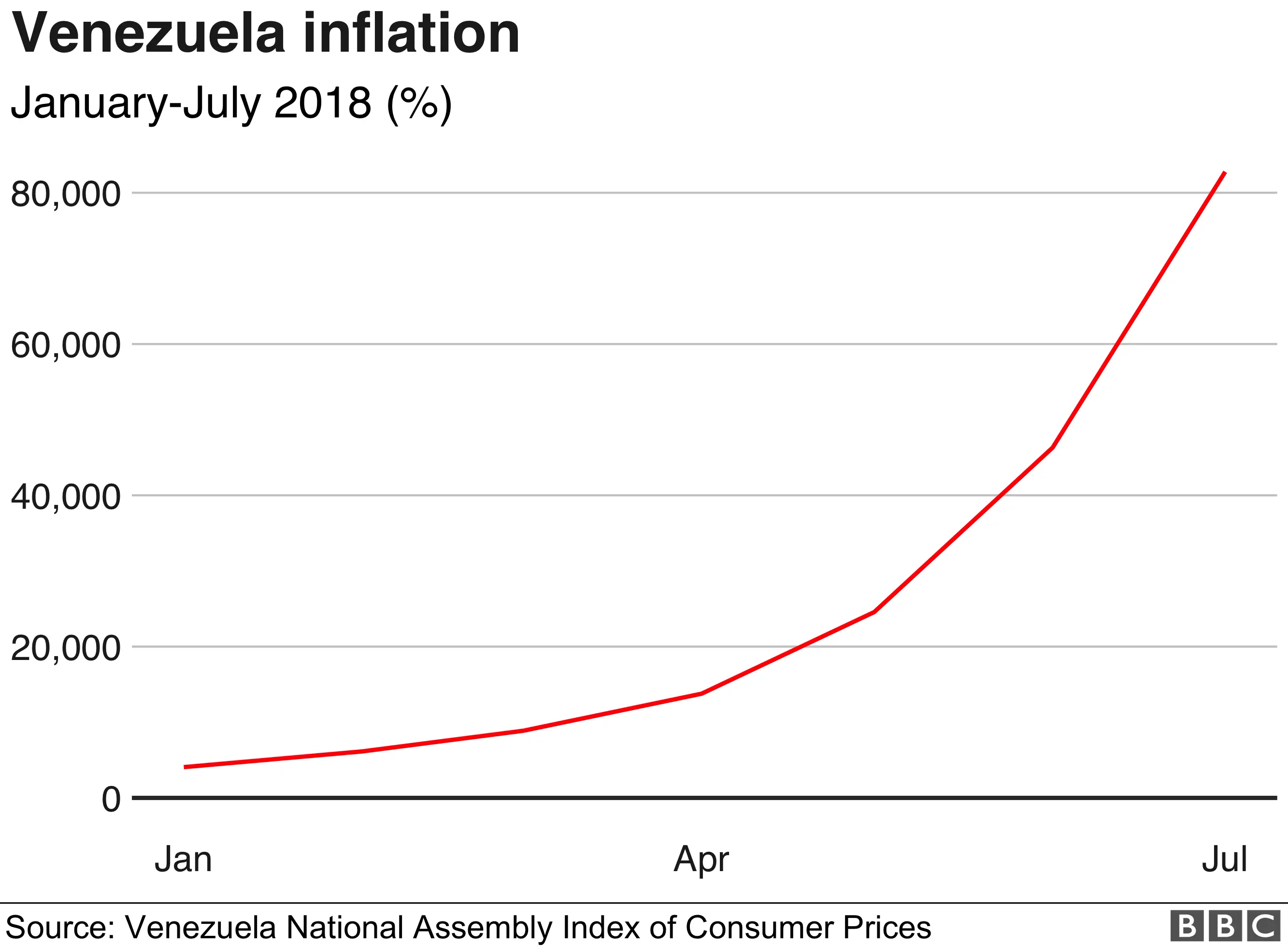

Venezuela has been suffering from hyperinflation. According to a recent study by the opposition-controlled National Assembly, prices have been doubling every 26 days on average.

Some economists have been using the price of a cup of coffee with milk as an indicator of inflation.

On 31 July cafes in the capital, Caracas, charged 2.5m strong bolivars for a cup, about double the amount recorded five weeks earlier.

Under the new system, the drink will now cost 25 sovereign bolivars.

Will this make things easier?

For a time, it should make cash transactions easier. Someone wanting to pay for their cup of coffee in cash until now had to carry huge wads of banknotes.

The biggest denomination in the old currency was the 100,000 strong bolivar note. So the minimum amount of notes you could pay your coffee with would have been 25.

High denomination banknotes were very sought after and banks imposed strict restrictions on how much cash each customer could take out of their account per day.

So Venezuelans would find themselves paying either with rucksacks full of lower denomination bills or increasingly avoiding paying by cash altogether and transferring money electronically.

As the BBC's South America correspondent Katy Watson found, even tips were being paid via bank transfer.

Will the new currency stop inflation?

The government hopes that its new economic plan will not only curb the country's hyperinflation but also put an end to the "economic war" which it says has been waged against it by "imperialist forces".

It says the introduction of the new currency is accompanied by key measures which will help Venezuela's battered economy recover. Among them are:

- Raising the minimum wage to 34 times its previous level from 1 September

- Anchoring the sovereign bolivar to the petro, a virtual currency the government says is linked to Venezuela's oil reserves

- Curbing Venezuela's generous fuel subsidies for those not in possession of a "Fatherland ID"

- Raising VAT by 4% to 16%

But economists have been warning that the new measures do not address the root causes of inflation in Venezuela and that the printing of new notes could exacerbate inflation rather than curb it.

They say the rise in the minimum wage will only drive inflation up faster. Some analysts estimate that the benefits of the new currency could be wiped out by hyperinflation "within months".

What immediate effect is the change likely to have?

Even though Monday is the date on which the new notes were due to be introduced, President Maduro declared it a bank holiday.

Not only will banks remain closed, financial institutions have also been told to suspend all electronic transactions for 24 hours starting at 18:00 local time on Sunday.

The new notes will therefore not start circulating until Tuesday and with long queues forming at banks even on average days many Venezuelans fear the sudden introduction of the new currency could lead to chaos.

Ahead of the changes, many Venezuelans stocked up on whatever staple goods they could get hold of amid longstanding shortages.

EPA

EPAEconomic experts have also questioned the wisdom of anchoring the new currency to the petro.

Even though the government says the virtual currency has been a huge success, details of how it operates have been hard to come by.

The US has banned its citizens from trading in it and one cryptocurrency site, ICOindex.com, has even labelled the petro "a scam".

"Anchoring the bolivar to the petro is anchoring it to nothing," economist Luis Vicente León told AFP news agency.