Patrolling Mexico's most densely populated suburb

BBC

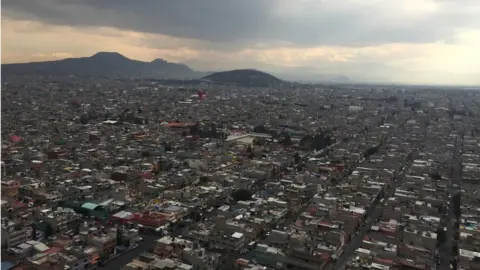

BBCFlying over Nezahualcóyotl in a police helicopter gives a sense of the challenges its residents face.

Originally built on the drained bed of Lake Texcoco, the suburb stretches out below in a patchwork of low-income housing with more than a million people crammed inside.

Ciudad Neza, as it is commonly known, is now the most densely populated place in Mexico, part of the vast urban sprawl outside Mexico City.

Over the years. criminal networks have taken hold, often with the complicity of local police.

Municipal officers insist they have changed, saying that their force has been purged, that corruption is being weeded out and replaced with a sense of civic duty.

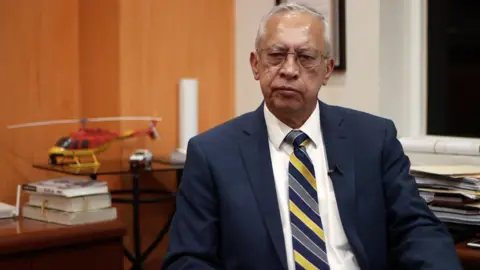

The man they credit for the turnaround is Jorge Amador, a former sociology professor turned police chief.

"I think we've broken with the traditional way of thinking on local policing here," he says, in a rare show of pride.

"Unfortunately all too often in our country police chiefs and politicians have seen security not as a public service but as a business, as a way to make money."

Purge

When he was first appointed to oversee security in Neza a decade ago, Jorge Amador began by removing more than 100 corrupt or unfit officers.

He also improved wages and conditions for those who stayed. Some of his ideas were considered unorthodox, such as promoting literature and chess among his officers.

But the intention, he says, was to combat "inertia", a term he uses often.

"We had to tackle that inertia, and dignify the role of a police officer once again."

Chess competitions and poetry readings among police officers is all well and good, but as many analysts point out, Mexico's problems run deep.

Last year was the most violent year in the country's drug war with more than 23,000 people killed.

With their key leaders either dead or arrested, several drug cartels splintered and battled each other for control.

Boots on the ground

For two consecutive administrations, the Mexican army has been deployed to try to bring peace to the streets, often playing the role of the police in many communities.

AFP

AFPNow the Mexican government wants to make that role permanent by law.

The "Interior Security Law" is deeply controversial given the army's poor human rights record and prominent activists such as José Antonio Guevara have grave reservations.

"In carrying out these police duties over the past 12 years, the army has tortured thousands of people and has disappeared and summarily executed many thousands more," he argues.

Specifically he referred to notorious incidents like the disappearance and subsequent murder of 43 student teachers in Ayotzinapa in 2014.

The BBC requested an interview with the Mexican military and the ministry of interior but none was granted.

At the local level, Mr Amador also does not think that the answer lies with the army.

"For us, security comes from bringing society closer together, from a closer relationship between the people and their institutions."

Different approach

So he tried two other approaches in Neza instead. The first was to introduce new technology.

In a nerve centre at police headquarters, the officers can see every corner of Neza via a sophisticated system of CCTV cameras. A network of neighbourhood watch groups was also set up, which is directly in touch with the patrols via WhatsApp.

There was also a return to some very basic community policing.

For example, the municipality was divided up into smaller units comprised of just three or four blocks. The local officers now hold regular neighbourhood meetings in the evenings so people can air their grievances in the open.

At one such meeting, it was clear that although car theft and violent crime are well below the national average, no-one was under the impression that Neza was now crime-free.

Residents did say that had noticed some improvements though. "It's not perfect but we've started to work together at last," Sandra said.

"At least when we ask the officers for help, they come out much quicker than before."

Her neighbour, Gerardo, pointed to a street alarm installed by the police. "We report anything strange or suspicious that we see. And when that alarm goes off, I've seen neighbours come out half dressed and with a spade in their hands to defend our street from criminals!"

It is an election year in Mexico and security remains a key campaign issue.

Many Mexicans believe their local police cannot be trusted.

While in much of the country that may be true, Neza's unconventional police chief claims he has proven officers are not all bad apples, rotten to the core.

"We have to challenge this idea that police in Mexico are corrupt, inefficient, criminal, abusive. That this is how they are and how they'll always be."