The avocado police protecting Mexico's green gold

Tancítaro looks and feels like a typical Mexican town: There is a central square with a bandstand and a little church.

A mariachi band is playing as I arrive. The music is part of a funeral procession with Tancítaro residents watching on.

But there is something that makes this quaint little town feel different. The pickup trucks ubiquitous in Mexico are shinier and newer here.

Tancítaro is powered on avocados, its people are rich from Mexico's green gold. This town is known as Mexico's avocado capital.

The municipality of about 30,000 people produces enough avocados to satisfy the demand of all of California.

Mexico produces about 45% of the world's avocados and Michoacán is Mexico's largest avocado-producing state.

From here alone, nearly two billion avocados are shipped to the US every year.

And because the industry is a lucrative one, it has been the target of organised crime.

As you enter Tancítaro, there are a series of checkpoints. They are known as filtros, or filters, by people here.

Some are more informal than others. One has a few sandbags and some elderly men sitting on a broken car seat outside a hut.

We pass another one with several pickup trucks standing outside. I notice a man with a rifle across his back. This is a well-armed town.

Michoacán is where the "war on drugs" started in 2006.

The strategy was launched by the then-president, Felipe Calderón, and its aim was to crack down on drug cartels by sending in troops.

But far from solving the problem of drug-related killings, it caused the cartels to fragment and violence increased further as rival factions fought each other for control of the drugs trade.

"From 2007, armed people started coming," says the mayor of Tancítaro, Arturo Olivera Gutiérrez.

"They started to pressure local authorities, to take control of the local police and take over the population through fear. Many people disappeared, they started killing, intimidating, taking over land."

In the absence of an effective police force, communities armed themselves to ensure the security of their towns, leading to the emergence in 2013 of "self-defence groups" in Michoacán.

The same happened in Tancítaro, too.

But while in other parts of Michoacán the self-defence groups were taken over by organised crime or dismantled by government forces, residents of Tancítaro did something different.

Avocado police

On one side of the town's main square is the headquarters of Tancítaro's public security body (CUSEPT).

There are nine or 10 people standing outside wearing body armour and carrying guns.

"The self-defence groups freed the municipality from organised crime and then, in conjunction with the government, we worked with the avocado producers to recruit police," explains José Hugo Sánchez Mendoza, the head of CUSEPT.

"The first prerequisite was that the force be made up of people from this municipality."

The police force is part-funded by avocado producers, who pay a percentage of their earnings depending on how many hectares they own.

The municipal government also contributes to the force and its members get training from federal forces.

Everyone in CUSEPT is connected to the avocado trade in some form, which Tancítaro's mayor reckons is its recipe for success.

People have a lot to lose and want to protect it, he explains.

They also have money. Their equipment is impressive. They all carry arms, wear body armour and have a bullet-proof pickup.

On one of their patrols, I sit next to Lorena Flores, who has her own farm.

She tells me she signed up because she was fed up with paying extortion to criminals.

She works with the force from Monday to Friday, eight to four. The time off is spent on her farm. She says that life here is much safer now.

Community watchdogs

At one point we stop at a junction where there is a checkpoint, a two-storey house painted in camouflage colours.

Opposite the checkpoint is a group of men, chatting by their cars.

They are one of 16 different community groups that work with police here, tipping them off about anything that is suspicious.

The men told me they had weapons but did not want to show me.

The police say the community groups do not carry guns openly but that they are there to help the police and inform them.

It is a bit of a grey area but one that seems to work for the town.

Better safe than sorry

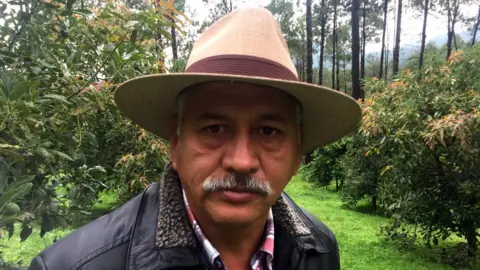

Later I meet Chema Flores, a wealthy farmer who has been in the avocado business since 1982.

He says he never imagined the demand for avocados would take off the way it has.

It has changed his life for good and bad.

Down the side of the driver's seat I spot a huge gun. I ask him why he has it.

"At the moment, here it's safe, there's lots of security but in other areas it's ugly, I don't want to lie," he tells me.

"They kidnapped my son when he was 16. They asked for $1m [£760,000] but I only had $500,000 to give them. I was also kidnapped twice."

He tells me he has permission to carry a gun and employs four armed bodyguards to protect him and his son around the clock.

The need for such security feels extreme for a farmer but you can see how the alternative could be worse.

Everyone in the town tells me that there are no kidnappings, no extortions now.

Producers like Lorena and Chema can sleep sound at night.

Tancítaro's heavily armed avocado police in its own way is a bright spot in a dark period for Mexico.

This year so far is the deadliest for the country in two decades.