Odebrecht case: Politicians worldwide suspected in bribery scandal

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt is the corruption probe that has left politicians around the world looking over their shoulders.

Prosecutors in a dozen countries are untangling a massive web of corruption that ran across a continent and further afield.

Illegal payments may have sloshed through presidential campaigns, boosted the careers of political top brass in country after country, and oiled the wheels of worldwide construction projects including motorways, gas pipelines and hydroelectric dams.

If you have never heard of a company called Odebrecht, you probably do not live in Latin America.

It is a Brazilian construction giant behind venues for the 2016 Olympics, infrastructure for the 2014 World Cup and the metro system in Caracas, plus dams and airport terminals further afield.

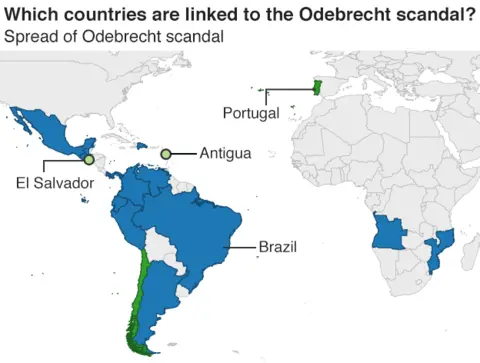

But anti-corruption investigators caught up with the company, and it admitted paying bribes in more than half of the countries in Latin America, as well as in Angola and Mozambique in Africa.

How high up did bribery go?

Odebrecht played a game of quid pro quo: I will help you pay for your election campaign if you make sure I get that building contract.

In country after country, it is alleged that Odebrecht employees made connections with those in power and those who looked like they would be getting into power soon. They did not restrict themselves to those of any particular political hue.

Almost a third of Brazil's government ministers who served under former president, Michel Temer, have faced investigation, including his foreign minister and chief of staff. The predecessor of current far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, who was arrested and released in a separate corruption case last month, is facing investigation in relation to Odebrecht. He denied all allegations of corruption and accused the country's judiciary of heeding rumours and destroying reputations.

The vice-president of Ecuador, Jorge Glas, became the highest-ranking government official to be convicted in the scandal when he was sentenced in December 2017 to six years in jail. Prosecutors said he took $13.5m (£10.2m) in bribes from Odebrecht.

Colombia charged a former vice-minister for transport and a former senator. The man who ran the election campaign of the former president, Juan Manuel Santos, has alleged it was financed with irregular Odebrecht payments. Mr Santos, who is a Nobel Peace Prize winner, said he did not authorise any payments or know about them.

AFP

AFPNext door in Venezuela, former chief prosecutor Luisa Ortega has fled the country after being sacked. She alleges that President Nicolás Maduro is implicated and that a top court is blocking an investigation. Odebrecht has denied her other allegation - that they paid $100m (£76.5m) to the socialist party's vice-president, Diosdado Cabello. Venezuela has taken unfinished projects away from Odebrecht and blocked the company's bank accounts.

In Peru, four ex-presidents have been placed under investigation. Ollanta Humala and his wife Nadine Herediaare are facing potentially lengthy prison sentences for allegedly receiving payments to fund his presidential campaigns in 2006 and 2011.

Alan García, who served as president from 1985 to 1990 and again from 2006 to 2011, killed himself with a bullet to the head on April 17 as police came to arrest him over claims he took bribes from Odebrecht.

Former President Alejandro Toledo, accused of taking $20m in bribes, is thought to be living in the US and the Peruvian government has put up a $30,000 reward for information leading to his arrest.

Staying with Peru, opposition leader Keiko Fujimori has come under preliminary investigation. The attorney general says a note found on Marcelo Odebrecht's mobile phone implicates her. She denied receiving money from the company.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPanama charged 17 people including government officials, and charged Odebrecht $59m in compensation. A lawyer from Mossack Fonseca - the firm at the centre of the Panama Papers leak - accused President Juan Carlos Varela of receiving Odebrecht donations. Mr Varela denies all wrongdoing.

Mexico summoned a former director of state oil company Pemex and other employees to give evidence over alleged Odebrecht bribes, while the Dominican Republic asked Odebrecht for $184m compensation over the next eight years.

Chile started an investigation and seized documents from the Odebrecht offices, while the firm agreed to pay Guatemala $17.9m in compensation for bribes paid to an official for public work, the attorney general's office said in January.

And Brazilian newspaper O Globo reports (in Portuguese) that 29 countries, including Sweden, the US, France and the UK asked Brazil for help with their own Odebrecht investigations.

Who is serving jail time?

Ecuador's vice-president Jorge Glas is serving a six-year term after he was convicted of taking $13.5m (£10.2m) in bribes from the firm.

Former CEO Marcelo Odebrecht started a 19-year jail term in 2016 after being convicted of paying more than $30m (£21m) in bribes to officials in Brazil's state oil company in exchange for contracts and influence.

AFP

AFPMore than 70 other Odebrecht executives were jailed but have agreed to plea deals, that is they agreed to provide information in exchange for more lenient sentences. Some are already out of jail and serving their sentences at home.

How they did it: The bribery department

The epicentre of the operation had a much more run-of-the-mill name, the Division of Structured Operations, but it was essentially the bribery department. Employees spent their time bribing government officials and political parties at home and abroad, to win business.

The company has admitted this to US, Brazilian and Swiss prosecutors. Money went through as many as four bank accounts in countries with good banking secrecy laws before getting to a recipient, usually an intermediary to someone with political power.

When the department's employees wanted to communicate, they used a system unconnected to the main computer systems, to avoid detection.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd they gave their recipients flippant codenames: Dracula, Sauerkraut, Decrepit, Totally Ugly. One politician, whose wife was 40 years younger than him, got the codename Viagra.

What effect has the scandal had?

Protesters have hit the streets over the Odebrecht case in country after country, and the chain of events has brought corruption to the top of news agendas and prosecutors' agendas.

They are "clamouring for justice", political analyst Geovanny Vicente Romero told the BBC

"Protesters are demanding people be held responsible for the negligence and corruption that are part and parcel of the historic inequalities in many of the region's countries," he said.

"Overall, people hope that the Odebrecht case will set a precedent so that these situations can be avoided in the future."

Reuters

ReutersWhat has happened to Odebrecht since?

The value of Odebrecht bonds was sliced. The downturn in construction that went alongside this contributed to a downturn in the Brazilian economy and the credit ratings agency Standard and Poor's cut the company to the lowest grading. It has recovered somewhat but is still far from excellent.

The investigations have even contributed to economic downturn in Brazil, and Peru shaved almost a point off its growth forecasts for 2017, which the government blamed on "the Odebrecht effect".

The company's website makes no mention of the scandal, but notes that "sweeping and profound changes in its transformation process" were undertaken in 2018, including the replacement of practically the entire Board of Directors to bring "greater diversity."

And there have been two CEOs since Marcelo Odebrecht was jailed - but tellingly, neither has had the surname Odebrecht.

Correction 26 September 2017: This article has been amended to remove a reference to Gaston Browne, the Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda. It was based on an interview in the Spanish newspaper El Pais. However, the paper has said its original source has not provided any evidence to support the allegations.