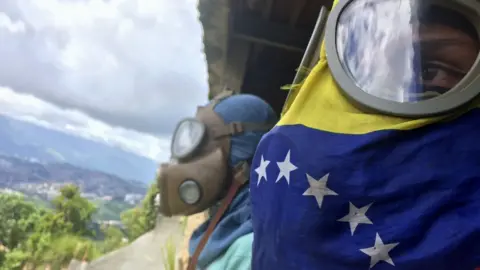

What lies ahead for divided Venezuela?

BBC

BBCWhat will be the aftermath of Venezuela's most controversial and violent election of recent times?

"Good morning! We have a new constituent assembly!" began President Nicolás Maduro as he greeted his supporters in the Plaza Bolívar in Caracas shortly after the electoral authorities announced the result.

The country's National Electoral Council said that just a little over eight million ballots had been cast for members of a a new assembly designed to change the country's constitution, a turnout of 41.53% of the electorate.

But the opposition boycotted the vote, guaranteeing victory for the country's socialist government, which had convened the vote. Amid the electoral violence, at least 10 deaths were reported across the country.

However President Maduro faces a real challenge of governability and credibility.

Perhaps the biggest is that every opposition supporter, and many millions of ordinary Venezuelans, simply do not believe the result.

"The government will claim eight million votes, but in reality it could have been about 3.5 million people," predicted pollster Luis Vicente León a day before the poll.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe opposition say several irregular electoral processes took place that in normal Venezuelan elections would not be allowed.

For example, no indelible ink was used to mark voters' little fingers after the ballots had been cast and critics say there was nothing to stop people voting in more than one polling centre.

There were also widespread reports of pressure being brought to bear on government employees to turn out in order to protect their jobs.

Several countries in the region - including Colombia, Argentina and Panama - said they would not recognise the result.

The United States also threatened "strong and swift action", with the US ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, calling the vote a "sham election" that brought Venezuela "another step toward dictatorship".

Nevertheless, the Maduro government is treating this result as a resounding endorsement and will press ahead with its plans to change the constitution. The first steps towards creating the new body could take place within 24 hours.

In part, the difficulty the Maduro government has faced in motivating its base stems from the many years they spent vociferously defending the same constitution they are now urgently trying to change.

Hugo Chávez himself often described the 1999 Constitution in sacred terms, comparing it to the Bible or the Mayan holy text, Popol Vuh.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe approach of most government officials has been twofold.

In part, they say the creation of a constituent assembly is the easiest route to peace - something that most ordinary Venezuelans are desperate to see return to their daily lives.

They also argue that this constitutional change is part of a vision of a "deeper" form of popular democracy that the late socialist leader was never able to fully realise before his death in 2013.

If so, however, he never made any great references to it while he was still alive: "Our constitution, one of the best in the world, is protected from the caprice of any political group," he said in 2008.

"In Venezuela, no-one can change a comma, a full stop, a letter of our Bolivarian Constitution. Only the Venezuelan people can do that through a national referendum," Mr Chávez explained.

A pro-government candidate standing in a low-income neighbourhood in the east of Caracas, Joaquin Mijares, denied that the vote was unconstitutional.

"The constituent assembly will be a space to discuss the direction of the country and how the state is organised," he said outside his local polling station.

"The process is legitimate because we, the people, are legitimising it with our participation."

However, the haemorrhaging of traditional Chavista support goes beyond this one controversial political process. It comes after months of food shortages, rampant inflation and worsening violence.

One does not have to look hard for signs of public exhaustion with the Maduro government.

"Sadly, my President, Hugo Chávez, died. Very sadly, because if he were alive, none of this would be happening," said Beatriz, a housewife in Catia, in western Caracas.

"I'll stay Chavista until the very end but I'm no Maduro supporter," she added. It is a position shared by many others among the nation's poor.

There is a uniquely Venezuelan word to describe the street closures and subsequent clashes with the authorities: "guarimba".

Now, with the votes cast, there is still no sign of the barricades and protests letting up.

If anything, positions are becoming more entrenched. "The Resistance" - a loose alliance of young, radicalised opposition protesters - have vowed to remain on the streets until the government concedes to their demands.

"We're going to be here until this country changes, until it improves, until the government falls," a 17-year-old protester manning the barricades told me.

"We need a president who's dignified enough to be called the president of Venezuela and an end to the shortages and queues."

The traditional opposition alliance, the MUD, also appears to remain committed to a campaign of demonstrations and civil disobedience. The government places the blame for the violence firmly at the door of the opposition.

But the head of the National Assembly, Julio Borges, denied that the MUD was responsible for leading the country down a path towards further conflict.

"We are not involved in a civil war in Venezuela," he said. "What we have in Venezuela is one people, one nation that is against a minority that has kidnapped power in the country."

On the other side, the military and the security forces are not backing down either. Despite suggestions of disillusionment among some sectors of the rank and file, there is little hard evidence of a genuine split or mutiny.

Both before the vote and in his victory speech, President Maduro spoke of dialogue. Some nations have been trying to table negotiations between the two sides with figures like former Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero attempting to broker some form of peace.

Spain, in particular, would want to see a stable Venezuela sooner rather than later, given its business interests in the South American nation.

However, there is little sign of a breakthrough. If anything, the decision to plough ahead with the election, despite widespread opposition, may have jeopardised any chance of further conversations for the time being.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFurthermore, despite the unity in the name of the opposition alliance, in reality the parties remain divided, split and without a clear leader who inspires Venezuelans. As such, the immediate outlook is bleak, says Luis Vicente León.

"It's absolutely going to get worse before it improves."

"The two groups both think they are in power. They both think they are going to destroy the other, that they are going to pulverise each other."

Such "mutually assured destruction", he argues, does nothing to tackle the problems of inflation, scarcity, poverty, lack of medicines and so on that have plagued Venezuela in recent years.

It seems, at least in the short term, Venezuelans face an unenviable and uncertain period as their country continues its gradual descent into anarchy.