The 'Robin Hood' policemen who stole from the Nazis

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDuring the German occupation of their island, a group of Guernsey policemen were deported to brutal labour camps in Nazi-occupied Europe after appearing before a British court. Their crime? Stealing food from the Germans to stop civilians from going hungry.

Not all of them survived. Some of those who did return home at the end of World War Two were suffering with debilitating diseases and had life-changing injuries, yet they were treated as criminals and denied their pensions.

Decades after what the men's families believe to be a dreadful injustice, some of them made one last attempt to clear their fathers' names.

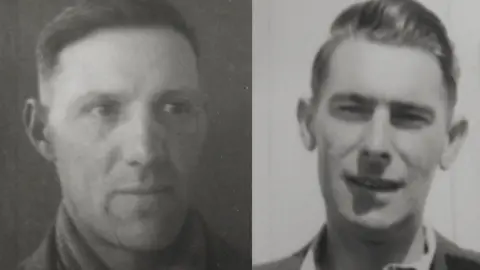

Island Archives

Island ArchivesCambridge University academic Dr Gilly Carr, who has spent years researching the five-year occupation of the Channel Islands, points out that the indignity of this time was in some ways even worse for the police than for civilians.

"Policemen were required to salute passing German officers, which they found hard to stomach," she said.

Constables Kingston Bailey and Frank Tuck began their first acts of resistance against the occupying forces by putting sand in the petrol tanks of their cars and painting "V for victory" signs around the island.

PA Media

PA MediaThe policemen were inspired by BBC broadcasts they would listen to in secret, which gave instructions on how to undermine the occupiers.

"For these young men who were denied the opportunity of fighting in the armed services, such broadcasts appealed greatly - and their role as policemen gave them opportunities for action denied to most," Dr Carr said.

In the winter of 1941-42, the civilian population was suffering from food shortages. The Germans had plentiful supplies.

And so Bailey and Tuck broke into the occupiers' stores at night, taking tinned food to share with those in need.

Bailey recounted in his memoirs that by February 1942 this covert operation was "getting out of hand… practically the whole police force was now taking part".

It wasn't long until Bailey and Tuck were caught red-handed by German soldiers lying in wait for them. Eventually 17 policemen were brought before Guernsey's Royal Court. Some were accused of stealing bottles of wine and spirits from islander-owned stores.

The Germans were alleged to have tortured some of the men during their interrogations.

One policeman, Archibald Tardif, recounted how he "was shown signed statements by other men and was eventually told that if I did not sign I would be shot, so I eventually signed.

"All these statements were typed in German."

Guernsey Archives

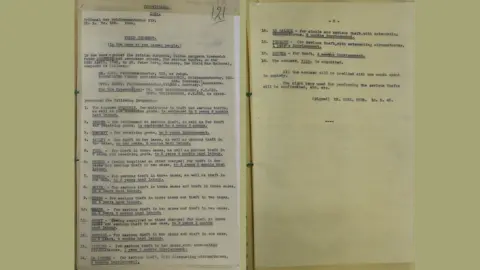

Guernsey ArchivesThe men were tried by both the German military court and Guernsey's Royal Court - effectively still a British court - and received sentences of up to four and a half years of hard labour.

Historian Dr Paul Sanders, who has worked on clearing the names of the men - all are now dead - said they didn't get a fair trial: "The British civilian court in 1942 acted like a kangaroo court in the worst dictatorship."

He said the men were told by the Guernsey authorities to plead guilty so the Germans would let them also be tried in the local court, where any conviction "would count for nothing after the war".

Sixteen policemen were deported to prisons and forced labour camps in Europe, where many experienced awful conditions.

Chris Webb HSS - Private Archive

Chris Webb HSS - Private ArchiveTuck wrote of the cruelty he experienced from guards: "I (was) kicked and knocked down and beaten with a pick handle and flogged with the butt of a rifle."

Herbert Smith was the only one of the policemen to die overseas.

Tuck recounts that Smith was "deprived of food and clothes when it was terribly cold… and beaten with a shovel and a pickaxe in the stomach" and left to die in a Gestapo prison.

When Charles Friend was liberated by US forces he weighed only seven stone (45kg) and was unable to use his legs.

Guernsey Archives

Guernsey ArchivesHe suffered for the rest of his life as a result of "those terrible days" and died in 1986 from a heart attack on the way to an exhibition featuring the story of what happened to him and his colleagues.

His son Keith said: "He was scarred by his experience both mentally and physically and never recovered from it."

Due to their criminal convictions, the men were unable to return to their roles in the police or claim a pension.

Mr Friend remembered his father being resentful of Guernsey's authorities, who had told him they would "sort everything out when he got back from prison".

"He was bitter and felt he'd been cheated by the local authorities who hadn't fulfilled their promise.

"I see what they did as a Robin Hood-type act. It's not a crime for personal gain; it was to feed hungry people, and as policemen they were in the position to do something about it."

Frank Tuck family

Frank Tuck familyAfter the war, most of the men applied to the West German government for compensation for their ordeals.

In 1955, eight of the men tried to appeal against their convictions but were unsuccessful on most counts, meaning they all had criminal convictions when they died.

The case was heard by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, which is the highest court of appeal for certain British territories, including Guernsey.

Dr Sanders said: "In the 1950s the illusion was upheld that British administration and justice in Guernsey had continued without being influenced by the Nazi occupation. This narrative continues right up until now."

Guernsey Archives

Guernsey ArchivesIn 2018, an approach was made to the Privy Council to re-examine the 1955 appeal for three of the men.

Barrister Patrick O'Connor QC, who took up the case pro bono, said: "It was a longstanding injustice for which the courts were responsible, and which the courts should therefore remedy."

The appeal was refused in March of this year.

In its ruling, the Privy Council said: "There are a number of difficulties with this application, including the fact that the complaint of mistreatment inducing confessions could have been raised before the Privy Council in 1955, but was not."

Mr O'Connor said: "There is no other procedure to overturn these convictions. Unfortunately, this leaves this show-trial as a stain against the Guernsey system of justice which will remain for good."

For Mr Friend, it was a blow that was hard to take.

"I was really disappointed," he said. "It seems so unfair, and there's still that stain on my family's character that shouldn't be there.

"It doesn't matter that they are all dead now, the record is still there."