Poland's Tusk-led pro-EU opposition signs deal and waits to govern

Attila Husejnow/SOPA Images/LightRocket

Attila Husejnow/SOPA Images/LightRocket Poland's opposition has agreed a coalition deal paving the way for them to form a new government following last month's parliamentary elections.

Leaders from Donald Tusk's centrist Civic Coalition signed the agreement in parliament with two other groups.

The pro-EU opposition won a comfortable majority in October's vote but will have to wait to form a government.

The ruling right-wing nationalist Law and Justice party (PiS) has been given the first crack at forming a coalition.

Earlier this week President Andrzej Duda handed the task to incumbent Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, as PiS won the 15 October vote as the largest party.

Mr Morawiecki has practically no chance of succeeding as all the other parties have ruled out working with Law and Justice.

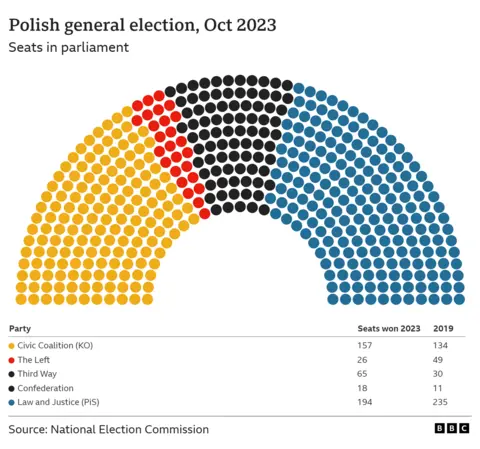

Although PiS won 194 out of the 460 seats in Poland's parliament, the Sejm, the opposition secured a majority with 248.

Civic Coalition (KO) signed the deal in the Sejm on Friday with the agrarian conservative Third Way party and the New Left, ahead of parliament's first sitting on 13 November.

They said they would nominate KO leader and former European Council chief Donald Tusk as candidate for prime minister.

"We are ready to take responsibility for Poland in the coming years," Mr Tusk told reporters.

The coalition deal set out broad policy goals, including strengthening Poland's position in the EU and Nato, with security a priority in the face of Russia's war in Ukraine.

They also pledged to remove political pressure on Poland's courts, overturn a 2020 ruling that almost completely outlawed all abortions, separate Church and State and depoliticise state media, military and special services.

"In our agreement, we found a common denominator for the issues we want to implement," said Wladyslaw Kosiniak-Kamysz, leader of the centre-right Polish Peasants' Party (PSL).

Despite the show of unity, part of the pro-Tusk bloc has said it will not officially take part in the coalition. The Together party, which ran as part of the New Left in the election, said it could not sign up because it did not go far enough in liberalising abortion and other parts of the deal such as increased spending on healthcare and education.

The party won nine seats and without them the Tusk coalition would still have a majority with 239 seats.

Poland's opposition wanted to sign a coalition deal ahead of the first sitting of the new parliament on 13 November to emphasise to President Duda they are ready to govern and have the numbers to do so.

They were quick to point out to the president, who is a PiS ally, that the right-wing nationalists were well short of the 231 seats needed.

But Mr Duda is a former PiS member and it is in PiS's interests to delay the process as much as possible in the hope that cracks appear within the opposition.

On Monday, MPs and parliamentary speakers will be sworn in and Mr Morawiecki and his government will resign, staying on as a caretaker government until a new government has been formed.

But it could take another month before that happens, or even longer.

From Monday, the president has 14 days to nominate a prime minister, and he has already made his choice clear. Mr Morawiecki then gets an additional 14 days to choose a team of ministers, draft a policy speech and win a vote of confidence.

Assuming he fails, parliament itself then has the right to designate a prime minister, which, given the make-up of the chamber, would likely appoint Donald Tusk as prime minister of a coalition government and give it a vote of confidence. Mr Duda has said he would appoint Mr Tusk if he is selected by MPs.

If Mr Morawiecki abandons trying to form a government due to lack of support, a new government could be formed this month. But not if he uses his speech to score political points.

Whatever happens, a Tusk government made up of members ranging from agrarian conservatives to the left would face significant challenges.

They are all pro-EU and in favour of restoring the independence of the courts and public media but differ on significant issues such as how far to liberalise Poland's stringent abortion law.