How Sinéad O'Connor changed Ireland

Agf/Shutterstock

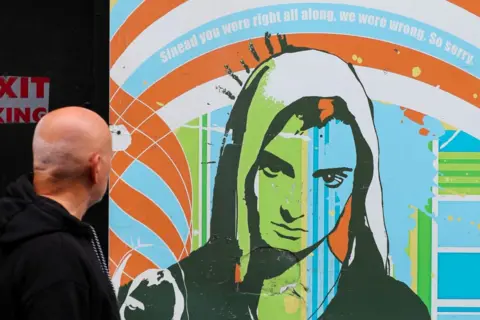

Agf/ShutterstockThe huge outpouring in the Irish Republic since the death of Sinéad O'Connor reflects a late realisation that she helped the country confront its own trauma, writes Una Mullally.

Underneath the oversized photographs of the Irish rock and roll Wall of Fame at a vigil this week in Dublin's Temple Bar, her image stood out amongst the mostly male artists.

How could it not? That's what she always did.

The grief took the form of a woman reading a poem in reaction to O'Connor's death. A small memorial shrine began to form with candles, incense, and flowers. "Thank you, Sinead" a sign drawn on cardboard read. "We heard you."

An a capella singsong took hold on the cobbled street. At her former house south of the city in Bray, another shrine coalesced. Further gatherings were planned in LGBT bars, on bridges, in public squares and a full moon vigil in Phoenix Park.

O'Connor's death has cracked open a complex and deep emotional network in the Irish psyche. Once again, through her, a pain about growing up in a place where little truth-telling occurred, is flowing.

Speaking out against the Catholic Church at a time when few people did sparked outrage and hostility and risked her career, but Ireland is now realising the good she did.

PA Media

PA MediaShe created connection. Seeing how she held herself, spoke, sang and acted, people projected on to her their desires to break free, to live authentic lives, to not care about what people thought, and to kick against the structures that told people - especially women, LGBTQ people and anyone who felt marginalised or divorced from straight, square, conservative society - to stay in their place and to do what they were told.

O'Connor was a lighthouse for those who felt adrift in Irish society. She offered a new moral compass beyond the lie of societal piety, one that pointed towards an uncharted direction of authenticity.

She rejected all notion of Catholic shame. While her actions were sometimes unfairly characterised as reckless, she was attempting to both expose and damn this shame. Far before people could converse fluently in therapy and wellness-speak, O'Connor identified the core problem of human strife and Irish self-loathing - childhood trauma. She equated the entire society's psyche to that of an abused child.

So when O'Connor broke through in 1987 with Mandinka, there's a reason, 36 years later, the lyric that's still roared the loudest is: "I don't know no shame, I feel no pain." She then embarked upon a career that was rooted in doing the sort of thing that often had severe consequences in Ireland - she rebelled.

O'Connor took that defiance across the Atlantic and it rebounded back to Ireland. Her appearance on Late Show with David Letterman in 1988 was a shock to multiple systems; Irish society, the music industry, the genre of female Irish alternative rock she was honing for herself. Her shaved head appeared to signal not just to punk but to a hidden gesture of humiliation imposed on women institutionalised in Ireland.

Reuters

ReutersFour years later, also on the set of an American television show, her tearing of the photograph of Pope John Paul II instigated a near-global moral panic and remains one of the greatest artistic acts of defiance and exposure in Irish history. She was right, of course. As the media piled on, in the years that followed, the stories of the brutality of child sexual abuse by clergy would define the trajectory of the Irish state.

She spoke about trauma. She talked about the impact of childhood on the adult psyche. She railed against the architecture of misogyny and abuse that she believed permeated the Catholic Church, yet never abandoned her own personal spirituality.

O'Connor embraced her sexuality while also defying the aesthetic markers of femininity, preferring leather and denim jackets, boots, ripped jeans and T-shirts.

Sinéad O'Connor's death

She was a punk, a counter-cultural hero, a mainstream success, a political radical, an iconoclast, a protest singer, a pop star, a rock icon, a folk and traditional music vocalist, a reggae aficionado, an emigrant, a mother, a poet, a person honed by society into becoming an activist, a priest, a Muslim, a feminist, an author, a sister, an actor, and to many, a hero whose source of inspiration was so steadfast that upon her passing, there is a visceral feeling of shock and sadness running through the country.

O'Connor may not have been someone whom everyone, at the time of her ascent, wanted, but she was certainly who we needed.

Shunned by America post-SNL, O'Connor continued to release music and tour. Her concerts were always packed. As a new generation discovered her artistry and power, something changed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the 21st Century crowds, there was a new energy, a joyous appreciation. Her 2021 memoir, Rememberings, reclaimed her narrative. She had won, because she had pursued an authentic life beyond the phoniness of the music industry structures, and she wanted everyone to know that.

Kathryn Ferguson's documentary that came the following year, Nothing Compares, pulled on this narrative, closing with scenes of Irish protest and progress on marriage equality and abortion rights, demonstrating how it was O'Connor's worldview that would ultimately be followed.

O'Connor had been right all along, and everyone knew it. Her resilience was a human manifestation of vindication. As Ireland became a more secular country, she was one of the leading voices for confronting the Catholic Church while maintaining a personal spirituality.

While her music has been ringing out from radio stations almost constantly since her passing, the stories being told are of her acts of solidarity. After her death, the band Massive Attack said: "The fire in her eyes made you understand that her activism was a soulful reflex and not a political gesture."

Reuters

ReutersIn recent days, people have recalled her attendance at reproductive rights marches in the early 1990s and her kindness towards the Traveller community, refugees, trans rights organisations, and the Dublin Aids Alliance.

She was part of a generation intent on dragging Ireland out of theocratic oppression, and towards a sense of empathy and liberation.

As she emerged, protested, sang, kicked up and never punched down, Irish society played that trick it does on so many - it embraced and rejected her, celebrated and demeaned her, appreciated and gaslit her.

She cared not about reputation, but about being heard. It is remarkable how her natural clarity of thought, something honed from being a deep thinker and reader, wrought confusion. And yet, in the bright light of the 21st Century, everything she was saying in the previous decades cuts through.

Her critics have long been silenced and the guilt that remains is theirs alone to carry.

Una Mullally is a journalist and broadcaster based in Dublin. She writes a column in the Irish Times