France riots: Nanterre rocked by killing and unrest

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCome to Nanterre to get an all-round view of the crisis boiling over in France. But if you are a journalist, be advised to keep your head down.

An approach to a group of young men - some bearded, one built like a bodybuilder - outside the Le 35 café prompts an aggressive outburst of swearing and a pointed finger directing me to keep out.

At the scene where police shot dead a 17-year-old boy of Algerian descent last Tuesday, women in Islamic headscarves shout abuse at police and the media from passing cars.

Wandering through the streets incognito - without a camera or notebook - past burned-out cars and smashed premises it is possible to pick up glimpses of the last catastrophic few days.

Three middle-aged white ladies, Lucille, Marie and Jeanne, are chatting with a black male friend on a bench outside their block of flats. The area is pristine, surrounded by gardens - like many other apartment blocks in Nanterre.

They don't want to be photographed as they fear their children would be identified and targeted as a result, but they are happy to chat.

"The last three nights have been appalling. Between midnight and 4am it is bedlam outside our windows. No-one can sleep. I feel like I'm living on another planet," says Lucille.

Do they perhaps not feel the anger from the rioters is understandable, when one of Nanterre's young residents, Nahel, has been shot dead at a police check?

"This rioting has nothing to do with what happened. Of course, the kid shouldn't have been killed. But what was he doing joyriding without a licence at eight o'clock in the morning, when children are going to school?"

Marie looks at a smashed bus-shelter daubed with graffiti that reads "one cop, one bullet".

"You see what it says there? That I am completely against. I don't think the police are racist. There are good and bad in every group of people," she says.

They have little time for the dead teenager's mother, Mounia, who took part in a mass march in memory of Nahel on Thursday.

"What was she doing up on that open-top van in the march? It was undignified. That wasn't a march of grief. She's playing politics." The others nod in agreement.

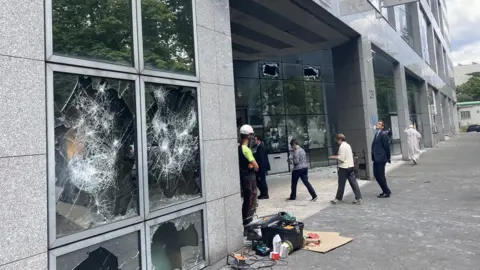

Not far away on the Avenue Georges Clemenceau, lined with plane trees, the préfet who heads the Hauts-de-Seine department has come to survey the wreckage that was the front of the local tax office. "Deplorable, lamentable," he says.

Firework rockets fired by rioters at the building have left gaping holes in upper-floor windows. At street level, every pane has been smashed with a heavy instrument. Charred tax forms are scattered outside the entrance.

Among the onlookers is tax inspector Cyril, who lives in Nanterre but also declines to be photographed.

"What I feel is just wretched sadness," he says. "This tax office serves the people of Nanterre. The money that comes from here is used to buy them services. What on earth is the point of attacking it? It's a totally disproportionate response."

Cyril, however, says he is broadly sympathetic with people who want to protest against Tuesday's killing.

"I'm not sure if racist police is correct. Let's just say they have an attitude. The kids around here have all had rough treatment, often because they were doing something stupid, sure.

"But look, this was a kid," says Cyril. "The officer was an adult. He had a gun. It was his job to be in control of the situation. And he wasn't."

YOAN VALAT/EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

YOAN VALAT/EPA-EFE/REX/ShutterstockThere are far stronger views, of course, among locals who took part in the memorial march.

Like Bakari, who doesn't justify the riots but believes they are understandable: "Certain people react against violence with violence."

"I wasn't surprised by [Nahel's killing] because we have all had bad experiences with police. There are good and bad everywhere, but the large majority of police are racist."

Or Yasmina: "I absolutely hate the French police. I wish them the worst. The whole system is corrupted by a systemic, racist ideology.

"[Nahel] could have been my kid brother. It blows my mind to think that a kid like that can make some stupid mistake, like anyone could do. He didn't deserve to die."

The town of Nanterre is far from the hellhole of isolated social deprivation some would like to depict. It is spacious, clean and two stops on the commuter train from the Arc de Triomphe in the centre of Paris.

The towers of La Défense business district are a stone's throw away.

There is a theatre, a university, the national opera dance school, and a large park named after former President Charles de Gaulle's culture minister André Malraux. Unfortunately, yesterday the children's roundabout that has stood there for the last 50 years was burned down.

The over-riding impression one takes away of the town is of two universes colliding.

On one level, all the standard accoutrements of the generous French state are plain to see.

Tricolours fly; the préfet comes to survey his domain; Metro trains whizz underground and, in the looming towers of La Défense multinationals make their billions.

But in the same geographic space, there is another way of being: one which appears utterly alienated from the system; which is quick to see and reflect hostility; which says "ici on est chez nous" - this patch is ours - and gives the finger to unwanted outsiders, like the press.

At a petrol station by the tax office, veteran Paris-Match photographer Eric Hadj is surveying his smashed-up car and preparing forms for the insurance claim.

"We were here on Thursday during the march. Some big guys came and told us to get out. They made it quite clear we risked something very nasty if we didn't. When we came back today, of course the car had been totally wrecked."

Hadj has been through a lot of riots in his time but says he has never seen anything like this.

"This is worse, far worse than 2005," he says.

Everyone here is looking back to the last sustained rioting that shook the French banlieues or suburbs for three weeks, wondering how long the latest unrest will last.

"Today there is social media, which gives the rioters a big advantage. But, above all, it is more violent. They have rockets. Whatever restraint there was has been removed," says the photographer.

Gérard Collomb, the former socialist mayor of Lyon and interior minister under President Macron, is well-known for his pithy sayings.

When he left office in 2018, he lamented the worrying tendency of French society to divide into communities - the very contradiction, he thought, of a single, unified Republic.

"Today we are living side by side," he said. "Tomorrow, I fear we will be face to face."

In Nanterre it is one face of France against another.