Ukraine war: 'It's better to die at home than abroad'

BBC/DAVY MCILVEEN

BBC/DAVY MCILVEENAt the train station in the eastern Ukrainian city of Dnipro, attendants in smart, traditional uniforms help passengers down the steep carriage steps.

Despite Russia's full-scale invasion, the trains here have never stopped running for the millions who rely on them.

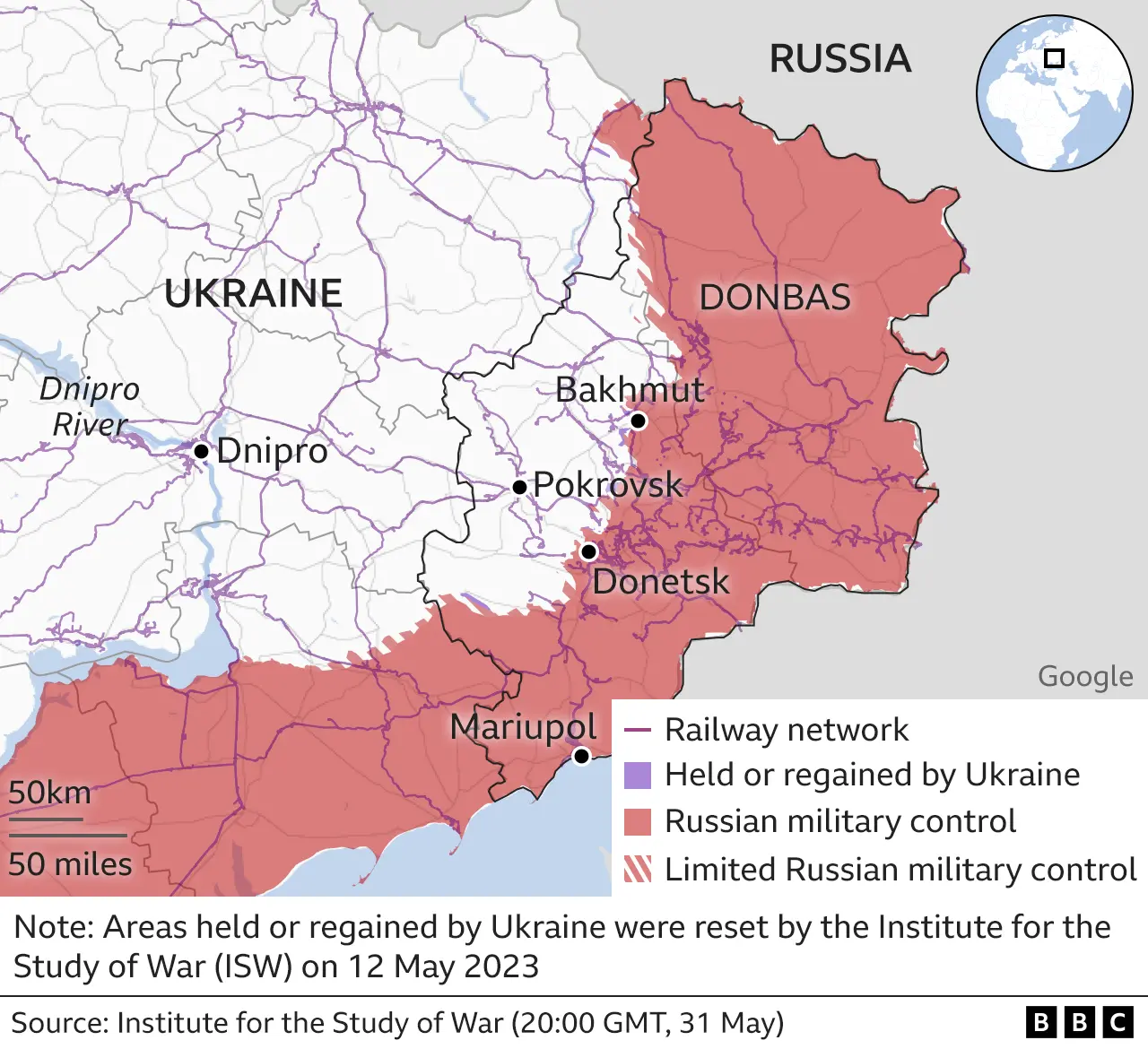

We board and take a journey people are being urged to avoid - to the last stop before the eastern front line.

As we weave past the protruding feet that line the stuffy sleeper carriage, it becomes clear this isn't just a route to the battlefield.

Yes, there are soldiers. Most look out of the window - you wonder what they're thinking about.

But there are also young families on their way back home.

BBC/HANNA CHORNOUS

BBC/HANNA CHORNOUSViktoria is heading back to the town of Pokrovsk with her baby Eva. The 20-year-old tells us she's had enough of avoiding the war, but isn't without worries.

"I have to overcome them somehow," she says. "It's impossible to live like this, wandering everywhere. We have to make it work at home."

Since February last year, Viktoria has travelled across Ukraine and Slovakia in an attempt to keep her and her daughter safe.

After three hours of weaving through the rich green of Ukraine's countryside, we arrive in Pokrovsk and Viktoria is greeted by the husband she left behind.

"I'm overwhelmed," says Serhiy, who was waiting patiently on the platform with a bunch of flowers.

"I'm very glad to see my beautiful daughter and wife. I just want us to sit, cuddle, chat and that's it."

Arrivals like this are part of a broader trend in Ukraine. After the devastating scenes of departure of last year, six million Ukrainians have since returned to their country.

Of those, thousands are moving back to their homes across the 600-mile (965km) front line, where the threat of a Russian attack remains.

Serhiy is one of many who stayed in Pokrovsk for his job at the local coal mine - an industry ingrained in the Donetsk region's DNA, and a major employer here.

BBC/DAVY MCILVEEN

BBC/DAVY MCILVEENNot only has it led to thousands staying, but it's also enticing people back with the offer of new jobs.

In the early hours, miners move with urgency to shuttle buses that take them to the mine shaft. Even once they're 800m (2,600ft) underground, it can take them up to an hour to walk to where they need to be.

Volodymyr has worked here for 20 years. Stuffed down the front of his overalls is his packed lunch. They call their food "tormozok" in these parts, which means a brake on their work at the mine.

He and some colleagues are protected from mobilisation because their roles are seen as critical. For Volodymyr, going to work is a balance between personal safety and simple economics. He must earn a living.

"When you go underground, you don't know what's happening above with the family. I'm often very worried."

Pokrovsk's population is gradually rising, after dropping by two-thirds last year from 65,000. Svitlana, who works in the station control room, said when the war began in 2022 it was "like an apocalypse - I had never seen so many people leave".

Now it's become a destination for those escaping Russian occupation and fighting.

It's a town very much on a war footing. The streets are filled with an even mix of civilians and soldiers. This area has seen war since the onset of Russia's aggression nine years ago.

Another attraction is the restoration of power and water by local officials, despite their warnings for people to stay away.

Pokrovsk is still comfortably in range of Russian multiple-rocket launcher systems (MRLS). Scars around the town remind you of their indiscriminate threat.

On the outskirts of Pokrovsk, closer to Russia's occupation, you find the town's last line of defence. Soldiers from the territorial defence keep a watchful eye towards the faint sounds of artillery.

Their dutiful actions are allowing people to move back into harm's way, and there seems to be sympathy in the trenches.

"Some are saving their children, some stay because it's their homeland," says Vyacheslav.

"If you have to die, it's better to die in your motherland than somewhere abroad."

BBC/DAVY MCILVEEN

BBC/DAVY MCILVEENA couple of days later we rejoin Serhiy, Viktoria and Eva at their flat. Watching them play with their daughter is a picture of innocence.

"Who knows when it will become safe here?" asks Serhiy. "Maybe a year? Two? Or five?

"We don't want to wait five years, or even one year."

They've clearly made peace with their decision to stay as a family, despite the obvious risks.

A move not just out of defiance, but from an acceptance, too, that this war won't end soon.

Additional reporting by Hanna Chornous and Siobhan Leahy.