Greek elections: Rail tragedy hangs over vote dominated by dynasties

Dimitris Plakias

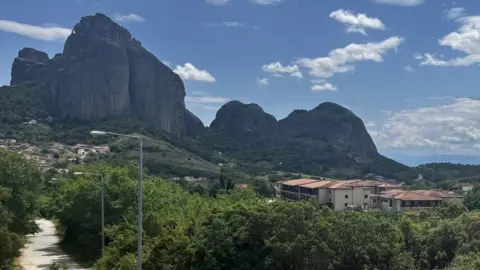

Dimitris PlakiasAs backdrops to polling stations go, the view from Kastraki primary school is about as spectacular as it gets.

Visitors are drawn to the scattering of monasteries perched on the edge of huge rocks above.

But beneath the surface of this striking natural beauty is a community consumed with grief.

That's because three of their brightest stars, who should have been voting for the first time, were killed in February in Greece's worst-ever train crash.

They were among 57 people who died when an intercity service carrying hundreds of passengers from Athens to Thessaloniki smashed head-on into a goods train on the same line.

Ahead of Sunday's general election, opposition parties have raised the disaster time and again as a symptom of a broken government and dysfunctional state.

Both Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis of centre-right New Democracy and his predecessor Alexis Tsipras of centre-left Syriza have visited the families bereaved by the Tempi train crash.

But above all, it is a story of personal loss.

"My Anastasia," Dimitris Plakias sighs, as he looks out from the terrace of his family restaurant. Tears well in his eyes as he describes his daughter.

"I'm fortunate I had her as a daughter, even for just a little while. I will always be proud. She was a rare girl and she only had love to give."

Anastasia and her twin cousins Thomi and Chrysa were travelling together on the passenger train.

They were all just 20 years old.

Like so many of the other victims, the young women were students returning to the University of Thessaloniki after spending a public holiday with their family.

An investigation found numerous failings.

"We relatives call it a state assassination of our children, and all the people who were aboard that train," says Anastasia's father. "In which European country could this be possible?"

Mr Plakias shakes his head when I ask if he has faith that any leader or party will help to prevent a similar catastrophe.

The sense of exasperation that nothing will change is compounded for many voters by the surnames on ballot papers up and down the land.

Greece is far from alone in being a cradle for political dynasties, but powerful family networks still dominate the stage, right along the ideological spectrum.

Kyriakos Mitsotakis's father was himself prime minister, his sister was foreign minister and his nephew is the current mayor of Athens.

SAKIS MITROLIDIS/AFP

SAKIS MITROLIDIS/AFPTwo hours' drive north of the rocks of Kastraki, in the village of Proti, we watch a taxi driver greet the statue of the founder of modern Greece, Konstantinos Karamanlis, a four-time prime minister and later president.

"Hello, big guy," he calls out to the community's famous son as he opens his boot to reveal a mass of glistening cherries he'll later sell to supplement his income.

But if Karamanlis immortalised in metal remains a giant from beyond the grave and beyond party lines, his nephew Kostas - himself the cousin of another prime minister - has faced national rage.

The day after the fatal train crash, Kostas Karamanlis resigned as transport minister, admitting the rail network he was responsible for was not fit for purpose.

However, the tears he shed in public as he surveyed the wreckage have not stopped him from standing for re-election this weekend, which has angered many of the grieving families.

In the village coffee house, we find sympathy for the bereaved, but also support for the youngest of the Karamanlis clan.

The owner introduces us to Giannis Sarigiannis, 79.

It turns out Giannis was a driver for the family, including the revered Konstantinos when he was prime minister.

I ask: couldn't the former transport minister also have resigned from politics as a sign of respect for the dead?

"It was not his fault, this crash," Giannis argues. "And as for his family, they are a good family. Modest people."

And that's why he's voting for the ruling New Democracy party, he concludes with a smile.

Head south to the capital Athens, and it's accusations of nepotism and clientelism that fuel the anger of many voters.

But like so many elections around the world at the moment, the high cost of living is the key consideration.

Outside a supermarket in a left-voting suburb, widowed pensioner Elena talks us through her latest shopping list.

"Bread, tomato, beans - the price of all of them has gone up," she says.

She will be voting for Syriza, the party that ruled from 2015 to 2019 - during the years of ongoing pain as the Greek bailout dictated strict spending measures.

Nicolas Economou/NurPhoto/Getty

Nicolas Economou/NurPhoto/GettyBut Greek GDP went up 6% last year, I put to Elena, citing EU figures.

"Oh well, that may well be the case, but I don't feel it. Everything I'm buying is going up 20-30%."

Despite the national economy bouncing back, more than a third of Greeks say they can't pay their bills each month - the highest proportion in the European Union.

If that is a prize no country wants, neither is the label Greece has just been given for the second year in a row - that of being the worst EU country for press freedom.

The adverse rating was largely down to what became known as Greece's Watergate.

Last year it emerged that politicians - including the leader of the third largest party - and journalists had been spied on using wiretaps and spyware that had infected their phones.

Greece's intelligence chief resigned, as did the prime minister's chief of staff - his own nephew - but the prime minister himself managed to hang on.

"It was a huge scandal," explains investigative journalist Eliza Triantafyllou, from independent outlet Inside Story.

She and her colleagues have relentlessly pursued the story, but it has not dominated the run-up to this election and she blames the mainstream media.

"They didn't make it a huge deal when it was first revealed and they just kept taking the answers of the government as truth."

If the polls are correct, no party will secure a majority, so Greeks are likely to face either a coalition government or a second vote in July.

That is partly down to the scrapping of a 50-seat bonus in the first round for the winning party in the 300-strong parliament.

Nick Malkoutzis, political analyst from Macropolis, say voters want to move on from a "lost decade".

"People can see there is perhaps a nascent economic recovery in the making and they have to decide in whose hands they are better off - and opinion polls show it's Mitsotakis they trust most."

The same old names may remain instrumental in Greek politics, but the voters may now look to them to share power.

Many go to the ballot box asking when Greece's economic growth will be shared too.

Additional reporting by Kostas Kallergis.