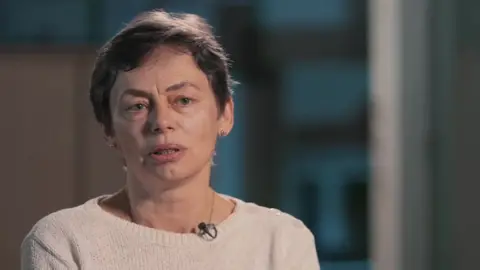

Vladimir Kara-Murza's mother speaks to the BBC

BBC

BBCImagine being in court and seeing your son - a government critic - sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Elena Gordon knows exactly how that feels.

Last month Elena stood beside the dock - a glass cage - in a Moscow courtroom. Locked inside it was her son Vladimir Kara-Murza.

One of President Putin's most vocal critics, he was convicted of treason and other alleged crimes and jailed for a quarter of a century.

Elena, who lives abroad, had flown to Moscow for the verdict.

"I was the only one from the family and friends to get into the courtroom," Elena tells me.

"Vladimir hadn't been aware that I would be there. So, he was a little bit shocked, but hopefully pleasantly surprised. I had been prepared [for this outcome], although I thought they would give him 24 years and eleven months, as a kind of an insult. In the end they decided to act blatantly. They gave him the maximum."

Since her son's conviction, Elena has managed to secure two meetings or svidaniya with Vladimir in jail.

"He's become very thin," Elena says.

"I'm worried about his health. But he's brave, obviously, and he says his spirit is unbroken.

"He is surprisingly optimistic. He believes in the future of Russia, and he believes in his own role in the future democratic Russia. But in terms of his own immediate future he is realistic. He is getting ready to be transferred to a penal colony."

Moscow court handout

Moscow court handout"What about you, his mother?" I ask Elena. "Are you optimistic or pessimistic?"

"I not only hope, I believe that I will see Vladimir free," she replies, "and I don't intend to wait twenty-five years for that."

For more than a decade Vladimir Kara-Murza has been a high-profile opponent of the Kremlin. He helped persuade Western governments to impose sanctions, including visa bans and asset freezes, on Russian officials engaged in corruption and human rights abuses.

Such persistent activism sparked anger in the corridors of Russian power. He survived two mysterious poisonings, which he and his supporters have linked to the Russian authorities.

In the West he spoke out against political persecution at home and against the Kremlin's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Last year, in a speech to lawmakers in the US state of Arizona, he condemned the "dictatorial regime in the Kremlin." Soon after he returned to Moscow where he was arrested.

"Vladimir must have known he was putting himself in danger by returning to Russia," I suggest to his mother. "Did you try to stop him coming back?"

"I did," replies Elena. "It's a painful topic for me, as a mother. I cannot distance myself and see him as a political figure only. He is first and utmost my son.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I begged him not to go back to Russia. He promised to think about this. And as you see, the result of his thinking was negative."

"Has he expressed any regret to you that he returned?"

"No, never. Never," says Elena. "I regret it very much. I speak for myself.

"He has principles. He really believes that he must be with his country and with his people, and that he would have no right to have a say in the future democratic Russia if he had fled and stayed in security."

Vladimir Kara-Murza's fate is a reminder of the danger in which politicians, activists, individuals who challenge the Kremlin are putting themselves. Most of Russia's leading opposition figures have either fled the country or are now in prison.

"I am afraid that Russia has turned into a dictatorship," says Elena Gordon. "To me it all looks rather grotesque, actually - that in the 21st century we see around us what was described in the anti-utopias of the 20th century. It's a terrible regression. It's a shame."