Ukraine war: Borrowed time for Bakhmut as Russians close in

BBC

BBCThe soil of Bakhmut is dusted with snow and soaked with blood. This small city in Eastern Ukraine is at the centre of an epic battle.

For more than six months Russian forces have tried to claim it. Ukrainian troops have resisted, giving rise to the popular slogan here "Bakhmut holds."

Now the Russians are attacking from three sides, with regular troops and fighters from the notorious Wagner mercenary group. The Russians have reached one of the main highways into the city, and are closing in on the outskirts.

There is house-to-house fighting in some areas on the outskirts, with "hard battles for every home" according to the Ukrainian military.

It feels like Bakhmut is on borrowed time. If so, Ilya and Oleksii intend to use every second of it.

The two Ukrainian National Guardsmen move swiftly and silently across open ground on the frontlines and then plunge into a trench.

Their camouflage backpacks contain weapons of war - a drone, a modified hand grenade, and a Velcro strap.

The German-made grenade had a tail fin attached, made with a 3D printer, to ensure it exploded on impact.

Ilya - an IT guy turned intelligence officer - makes short work of velcroing the grenade to the drone. Then he launches it towards enemy forces nestled in their trenches, a kilometre and a half away.

"We know there are a lot of Russian soldiers there, walking, living, and sitting," said Oleksii, the drone pilot. "And so, we just give them [a] gift."

"The aim is not to kill a lot of soldiers but to make them afraid of our sky, to make them watch out every second. It's psychological pressure."

He shows us a drone's eye view as he releases the grenade over a frozen expanse. We can see the impact on his screen but can't tell if they were casualties below.

Oleksii says the fighting in Bakhmut is tough, emotionally and physically: "It's hard, but we are staying here, and we will protect Bakhmut and the area around it as much as we can."

But Ukraine is counting the cost and there's speculation it could withdraw to avoid further heavy losses.

In the Kremlin, a clock is ticking - counting down to the first anniversary of Russia's invasion of its neighbour, on 24 February 2022. President Putin wants a victory before then. Taking Bakhmut would give him one, and bring him closer to his aim of capturing all of the mineral rich Donbas region.

To reach Bakhmut you drive along winding back roads. The route we used for previous trips last September is now classed as "suicidal" because of constant Russian attacks.

The city is now a shell. The thud of incoming and outgoing fire echoes through empty streets. Missiles have punched holes through buildings. Power and water supplies are long gone, along with most of the pre-war population of about 70,000.

But some families have remained here, with their children, sheltering in the shadows.

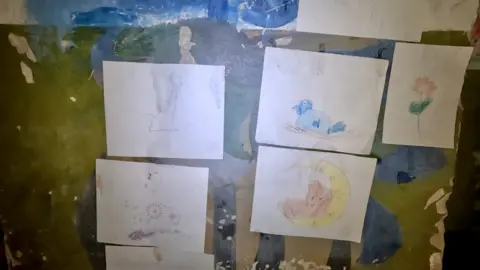

Anna, who is seven, is a bright spark in an airless dark basement. Tiny gold earrings glint in her ears, her blonde hair is tied back in a ponytail, and she's wearing a pink sweater. Her colourful drawings line the walls but it still feels like a prison cell.

Anna lives with her mother Yulia, grandfather Valery, two cats and Mushka the dog. She proudly shows us her favourite soft toys, but her blue eyes stand out against her pale complexion.

"I sit in the cellar almost all day long," she tells me in a lilting voice. "Outside I take Mushka for a walk, but she's afraid of these booms and constantly comes back. Only in the morning, when it is quiet at dawn, I can take her out."

Yulia sits in the gloom nearby, as Anna lists her friends who have already fled. "I miss them all," she says. "Arina might be in Poland, Masha in Western Ukraine. Diana went somewhere else. Everyone left."

But Yulia is staying put with her daughter. "Of course, I am worried," she tells me. "But I think it is more or less safe. At least we have everything here, everything is prepared. We think nowhere in Ukraine is safe and we have no means to go abroad."

Their basement shelter is well stocked with food and water, and they get regular deliveries from the White Angels, a unit of Ukrainian police who provide aid and carry out evacuations.

The team leader, Pavlo Dyachenko, lights up when he sees Anna. In the depths of war, they have forged a bond.

He has brought Anna a new sleeping bag to keep her warm, but he would rather be getting her and her family out of the line of fire.

"I don't understand why they are deciding to stay," he said. "Bakhmut is under attack in the evening, in the morning, in the night. It's very dangerous with bombing and shelling all the time."

More thuds above ground amplify his point.

The shelling usually intensifies as midday approaches - part of the rhythm of warfare in Bakhmut. After exhausting overnight battles, troops on both sides sleep late into the mornings, before getting back to their guns.

We race out of the city and onwards through rolling hills that offer a commanding view of the area.

"These heights are more important for the Russians than Bakhmut itself," said a Ukrainian colleague. "If they can bring their artillery here, they can target bigger cities like Kramatorsk and Slovyansk. "

Bakhmut holds, for now, but for how much longer.