Ukraine war: How pathologists identify victims of Russia's invasion

BBC

BBCOleh Podorozhnyy leads the way through the dimly lit corridors of his morgue, past windows covered with sandbags, to a large white container in the back yard.

As soon as its heavy metal door is cracked open, the cloying smell of death rushes out.

Piled inside in white bags are the remains of civilians killed when the town of Izyum was occupied by Russian troops. Many have been dead for months.

The body bags are marked with numbers and the barest of details, scrawled in black pen. Weeks after Izyum was liberated, the remains of 146 people found there have still not been identified.

They're here because the main morgue is overwhelmed with more unidentified bodies from Russian missile strikes and mass graves across the Kharkiv region.

"The number of bodies we have right now is really high," explains Oleh, a pathologist at the Kharkiv Bureau of Forensic Expertise.

"They all remain here while DNA tests are done."

There is a generator now but keeping the container cool during regular power cuts caused by Russian attacks on Ukraine's energy infrastructure is challenging.

The long search

A couple of hours' drive east in Izyum, the destruction from Russia's invasion is staggering.

A high-rise block of flats has a giant hole blown through the middle and all around, detached houses have been flattened.

A man up a cherry-picker is repainting a bright mural on to a fire-blackened building but there are big Zs daubed on a row of garages nearby, the tag of Russian soldiers during their seven-month-long occupation.

Living amongst all this are the families searching for relatives they know were killed, but who still have no body to bury.

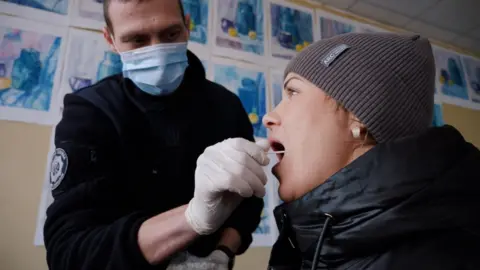

Izyum police station was destroyed, so officers have set up an incident room at an art college where they collect DNA samples as well as evidence of the atrocities here.

They call people in one by one and gently swab the inside of their cheeks. The samples are then sent to a forensics laboratory to extract a DNA profile in the hope of finding a genetic match with a body at the morgue.

After her turn, Tetyana Tabakina pauses in the middle of the room, hand over her mouth like she's stifling a sob.

Her sister, Iryna, and nephew, Yevheniy, were killed in a Russian airstrike on their block of flats in early March. They'd been sheltering in the basement where they thought they'd be safe.

Tetyana managed to identify Yevheniy by a tattoo on his arm but she has never found her sister.

"Ira was torn apart in the blast. I can't even find a piece of her," she says softly. "I'm waiting to find even a little piece of my sister, so I can bury them both together."

DNA difficulties

But the war that created Tetyana's nightmare is also making the identification process painfully slow.

When the Kharkiv region was invaded, forensics experts were among those fleeing to safety.

"We're training new people, but for now we only have eight people in our department and the workload's enormous," Viktoria Ionova explains.

She's a specialist at the laboratory trying to establish genetic profiles of the dead and of those searching for them.

"We also have issues with power cuts. The high-precision equipment suddenly stops working so we have to start all over again," Viktoria says. "We have a generator, but there have been times when we had no power for a whole day."

The way people died further complicates the scientists' work: many were badly burned in shelling and air strikes.

"When there is the maximum degree of burns, there is almost no genetic material," explains Oleh Podorozhnyy, the pathologist. "We send fragments of bone, but sometimes the experts can't extract a genetic sample so they ask for more. That's why it's so slow."

And not all the dead have close relatives still in Ukraine to provide swabs.

The prosecutor's office has published instructions of how refugees can provide samples abroad, and send them back for testing, but few have taken advantage of that.

Forest graves

The unidentified of Izyum were mostly found buried in a pine forest on the edge of town, beneath long rows of simple wooden crosses.

They were taken there by volunteer grave diggers when Izyum was occupied.

When Ukrainian forces retook the town in September, the bodies were exhumed and moved to Kharkiv. Police say some died of natural causes, but many were killed in shelling or explosions and 17 showed clear signs of torture, including rope around the neck and bound hands.

They've now exhumed 899 bodies across the region.

"It's very difficult, of course. We've never seen so many corpses. On average, we're exhuming about 10 a day and this work isn't over," explains Serhiy Bolvinov, head of police investigations for Kharkiv region.

This week his officers found the body of a man killed by a cluster bomb and buried in his garden by his wife.

"What happened here, the crimes Russia committed, will never be erased from our memory and we will investigate each one of them," he says.

In total, 451 bodies were found in Izyum, including seven children. Buried in the forest in haste and under fire, most had no coffin nor even a body bag.

Many also had no name: the wooden crosses on their graves were marked only with numbers.

One just reads: Lenin Avenue, 35/5, old man.

A poet's funeral

But the body that was buried as number 319 has now been identified. DNA tests established it as Volodymyr Vakulenko, a children's writer and poet.

Nine months after he died, his family were finally able to give him a funeral.

The poet was detained and interrogated by Russian forces in late March, then released. The next day, witnesses saw two soldiers leading him away again. They say he shouted "Glory to Ukraine!" then was bundled into a car with a Z on it.

When his skeleton was recovered from the pine forest, two bullets were found in his grave.

"You jackals! How could you?" his mother demanded of his killers at his funeral, bending over the coffin draped in the blue and yellow Ukrainian flag.

"God teaches us to forgive, but I will never forgive the murderers," Olena Ihnatenko said, hugging a framed photograph of her only son tightly to her chest.

"I will live in the hope and belief that the investigation finds who's responsible and that the killers will be punished. I will live for that dream."

Her son's friends have found a diary he kept at the beginning of the war and buried beneath a tree before his arrest. It talks of his fears as a prominent Ukrainian patriot in a small village occupied by the Russians.

"It is extremely dangerous for me to be encircled by the enemy," he wrote.

The last entry, scrawled on chequered notepaper, describes seeing a flock of cranes overhead: "Through their chirps I seemed to hear 'Everything will be Ukraine!'. I believe in victory!" the poet wrote.

The long wait

So far, only five bodies from Izyum have been identified using DNA. The forensics teams admit some are so badly damaged they may never be named.

For relatives, like Tetyana Tabakina, it's an agonising wait.

She says a neighbour recently buried seven family members killed in the same attack as her nephew and sister.

"He told me that the morning after their funerals it was like a great weight had been lifted and he was finally able to sleep again," Tetyana says.

"I just want to get through that moment, then maybe it will be easier for them. Or for me."

Produced by Tony Brown, Matt Goddard and Hanna Chornous