Kherson: As Russia retreats, Ukrainians still fear a trap

BBC

BBCNot long after the Russians announced they would be pulling out of Kherson, a text popped up on my phone.

It was from a resident of the city, who wanted to remain anonymous, giving me her impressions of what was happening.

"I've seen the announcement and I'm really surprised," she wrote.

"Of course, I hope things are going to get better, but during these eight months of occupation I learnt not to believe a word the Russians say. They lie so much about everything."

She could see Chechen fighters, loyal to Moscow, moving around the city, many wearing civilian clothes. Her concern, like so many of her fellow citizens, was that Russia's announcement could be a trap - designed to draw Ukrainian troops into a killing ground.

"I really hope they don't lie," went her next message, "and that they don't make traps for our Ukrainian army."

Since then, her account has been silent. Until the Russians declared their intention to pull out, internet connections, only available on Russian SIM cards, were patchy.

From this morning, not only has the internet mostly been down in Kherson, but supplies of electricity and water have been cut, according to messages coming out of the city.

Someone living under occupation for months might be forgiven for fearing the malign intentions of Kherson's occupiers.

But in the days before Moscow's announcement of a pullback - when rumours of it were widely reported - the first instinct of all the Ukrainians I met was that Russia was trying to lure their army into a trap.

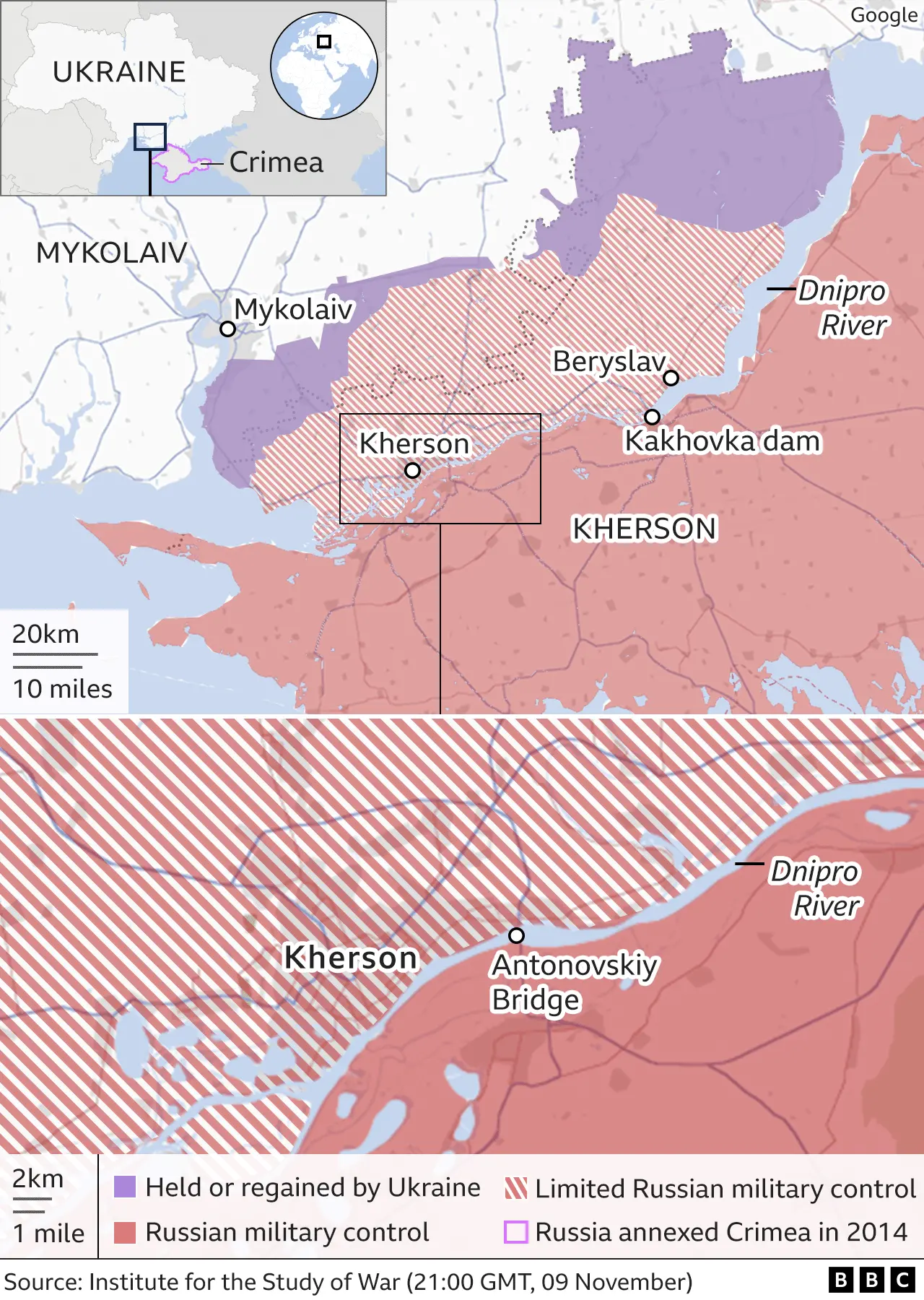

That was the strongly-held view of soldiers at a frontline mobile artillery unit on the flatlands where the two sides were still fighting - between Kherson and Mykolaiv, the nearest town controlled by Ukraine.

Russia's plans were not their biggest concern. The war, they insisted, was going to be fought on their timetable, not President Putin's. They believed in their own power and Ukraine's alliance with Nato.

All the same, their commander, whose nickname was Kurt, had firm ideas about Russia's intentions. "This is one of the ways they want to trap Ukrainian armed forces and surround our units," he said.

"But the Russians won't manage it. Our intelligence works much better than theirs. We know about their plans, and the kind of troops that are ahead of us. Step by step, we'll get to victory."

Wise commanders always project certainty. And if they have doubts, they share them only with trusted deputies - not their men - and certainly not visiting journalists.

But soldiers of all ranks on the Ukrainian side are almost always positive about winning the war. And, rightly, they regard Russia's decision to leave Kherson as a significant victory.

In Kherson, languishing under months of occupation, it has been much harder for Ukrainians to stay positive. We managed to reach a man there who said many of the Ukrainians there felt abandoned by the army and government in Kyiv.

"Frankly, morale is very low. People ran out of money; they have no medical help. We've been told for half a year or more that Kherson is going to liberated, but nothing changes. That's why Khersonites do not believe anything any more."

He will not believe the hour of liberation has come until he sees Ukrainian soldiers driving down the street.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIf there is to be a Russian trap, the chances are that they would want to spring it at the moment Ukrainian forces advance.

Russian troops could leave booby-trapped buildings, mines and roadside bombs. Once Ukrainians move forward, they would become targets for Russian artillery on the left, or eastern bank of the river.

Russia has built a double line of fortifications east of the Dnipro, and along with the mighty river itself, it would all amount to a formidable series of hazards and obstacles.

That is why, since the Russians said they were leaving Kherson, Ukrainian commanders have emphasised caution.

A special forces officer, who runs what he calls "partisan warfare" inside Kherson, reflected a common attitude to casualties. Like other interviewees, he did not want to be named, in his case because of the secret nature of his job.

"We've got one more task. To save the lives of our soldiers. As of today, Russians have got strong fortifications on the other bank of the river. If you go on a frontal attack, it will lead to mass death of people. Our commandment has got other goals."

Russia sounds serious about the withdrawal. It was announced by the country's military leaders on national television. President Putin was not in the broadcast, but in the end, it would have to be his decision.

It is without question a serious defeat. But is is less a newly-inflicted wound, than an acknowledgement that Moscow's plan to seize much of Ukraine's Black Sea coast failed months ago.

Russia has been under pressure in Kherson, but its defences have mostly been holding. Withdrawals have been slow and advancing Ukrainians have been hit hard by artillery.

Gen Sergei Surovikin, appointed only a month or so as Russian commander in Ukraine, might have presented the decision to President Putin as the least bad option - and one with possibilities of stabilising the front before the Ukrainians could inflict another defeat.

Gen Surovikin might have asked what the point of a continued occupation of Kherson and the surrounding area was, in the face of a slow defeat.

It has been clear for months that Russia's plan to use Kherson as a jumping-up point for a push along the coast towards Odesa, a major port, had failed. Ukraine, after all, stopped Russia's thrust in the spring.

Since then, Putin's men have hammered neighbouring Mykolaiv with artillery from the big pocket of farmland west of the river Dnipro, which they seized at the same time as the city of Kherson.

Perhaps Gen Surovikin's argument was something like this. Miles and miles of flat fields and farmland on the west bank of the Dnipro, separated from Moscow's main supplies by the river, were always going to be hard to defend.

Pulling back to prepared positions east of the Dnipro would create a serious obstacle to another Ukrainian advance.

If Ukraine loses its sense of caution, and pushes forward too fast to exploit Russia's retreat, Gen Surovikin might be able to spring a trap and inflict serious losses. If that happened, he could present the withdrawal as one of the better Russian decisions in this war.

For their part, Ukrainian generals will try to punish the Russians as they retreat; to do their best to turn a retreat across the river Dnipro into a trap of Russia's own making.

A Russian retreat over the Dnipro is not the end of the war. Far from it.