France calls time on anti-jihadist Operation Barkhane in Sahel

AFP

AFPPresident Macron will use a speech in Toulon on Wednesday to bring to an official end France's eight-year anti-jihadist operation in the Sahel.

Operation Barkhane has been inoperative since February, when France announced its military withdrawal from Mali.

The last French troops left their base in the Malian town of Gao on 15 August.

According to the Élysée Palace, Mr Macron wants to spell out new priorities that from now on will govern military interventions in Africa.

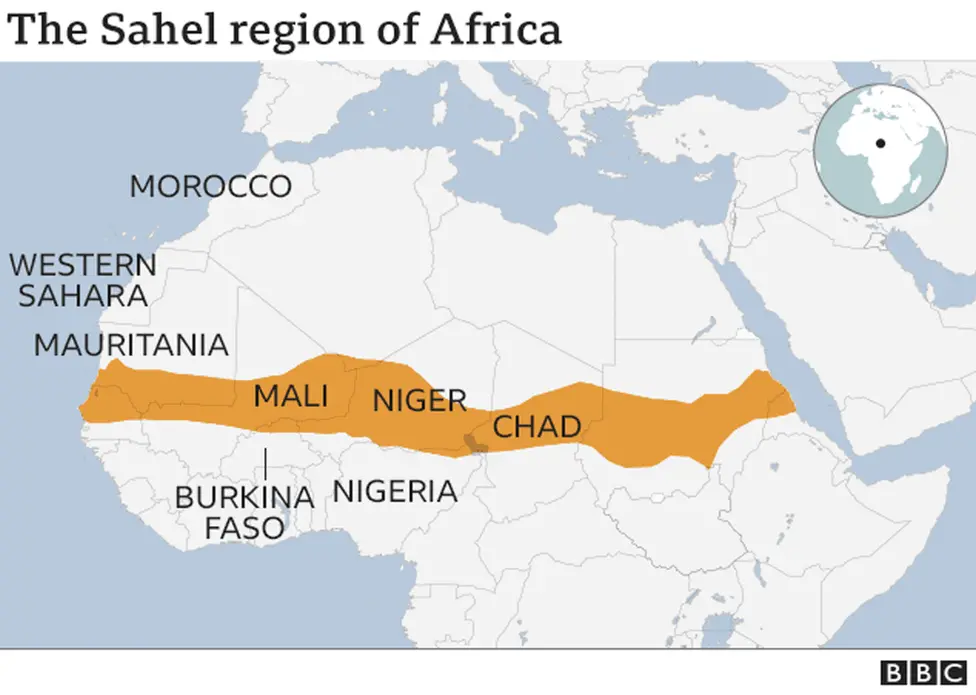

At its high point, there were 5,500 French troops taking part in Operation Barkhane, which was initially launched in 2013 to stem the advance of jihadist insurgents in Mali. The other countries in the partnership were Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso and Mauritania.

But faced with the continuing spread in the region of groups linked to al-Qaeda and Islamic State - as well as a growing casualty list of French troops (58 dead) - military leaders and politicians in Paris became increasingly doubtful of the viability of the campaign.

Mounting hostility to France among local populations - fanned by social media and widespread disinformation - made the task a thankless as well as a dangerous one. The last straw was the 2020 coup in Mali, whose leaders accused France of interference and turned instead for security to Russian mercenary group Wagner.

Mr Macron, who wants to to draw a public line under the campaign, is expected to say that France is not abandoning the fight against Islamist militants in the region, but that its efforts will now take place under different terms of engagement.

Some 3,000 French troops will remain in Niger, Chad and Burkina Faso - but they will not act independently, only in co-ordinated actions with national armies. Significantly, this continuing deployment will have no official name, indicating that it is no longer an "external operation" as Barkhane was.

Analysts say France had little choice but to acknowledge the failure of Barkhane after the junta in Mali abruptly terminated relations.

"The initial aim was to stop the spread of jihadism in the Sahel and to forge a strong partnership with the Malian army," said Elie Tenenbaum, defence specialist at the French Institute for International Relations (IFRI).

"Today that strategic partnership is in tatters… while jihadism extends itself ever wider in the region, and roots itself more deeply in society."

AFP

AFPWest Africa regional analyst Paul Melly said the Sahel security crisis was severe and probably spreading: "Conditions in north-east Mali are now very fragile. This worsens the security threat to northern Burkina and western Niger."

Other outside factors have also forced a rethink in Paris. The war in Ukraine has shown there are strategic priorities on France's own doorstep, and that limited military resources might be better directed elsewhere than in a losing war in Africa.

Also, in the battle for influence in Africa that is being fought over the internet and social media, France has the unpleasant feeling that it is being outsmarted by more unscrupulous players - not least Russia.

The recent coup in Burkina Faso - when anti-French protesters were filmed waving Russian flags - was seen as more proof of the way hostile propaganda is turning people in the region against France.

"When France is there, it is accused of interference. When it is not there, it is accused of abandonment. Whatever it does, France is wrong," veteran Africa reporter Patrick Robert wrote recently in Le Figaro.

This latest redeployment is an effort not just to reduce the exposure of French troops on the ground, but also to win over more African hearts and minds.