What Congress can learn from country with youngest lawmakers

Maren Grøthe

Maren Grøthe America's leaders are old and growing older. As part of a new series that looks abroad for inspiration on how to fix flaws in the US political system, we ask whether Norway's young MPs have the answer.

Democratic President Joe Biden, 79, is the country's oldest ever leader. His chief rival, Republican Donald Trump, is 76.

In the US Congress, the median age is the highest in two decades. Baby boomers dominate and millennials represent barely 6% of the body.

Midterm elections this November will reshuffle the makeup of the legislative branch of government - but many of its oldest faces will remain.

The problem is a structural one, according to experts.

Congress prizes seniority, with the longest-tenured lawmakers typically first in line for leadership posts, plum committee assignments and other forms of influence. Name recognition and visibility gives incumbents a smoother path to re-election.

Making matters worse are the age requirements. You must be at least 25 to join the House of Representatives, the lower chamber of Congress, and at least 30 to qualify for the Senate.

Meanwhile, young hopefuls face financial barriers to seeking office with fewer resources, less access to wealth and obstacles like childcare costs or student debt.

Some believe youth under-representation has had a profound impact on US democracy.

"Lived experience informs legislative priorities," says Amanda Litman, co-founder of Run for Something, a group that supports progressive candidates under 40.

She claims that a lack of progress on issues young people care about, such as gun violence and climate change, have fed "a cycle of cynicism" and disengagement.

Norway has the highest proportion of young politicians in the world, according to data published by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), with 13.6% under 30.

In the US, it's 0.23% in the House of Representatives and zero in the Senate.

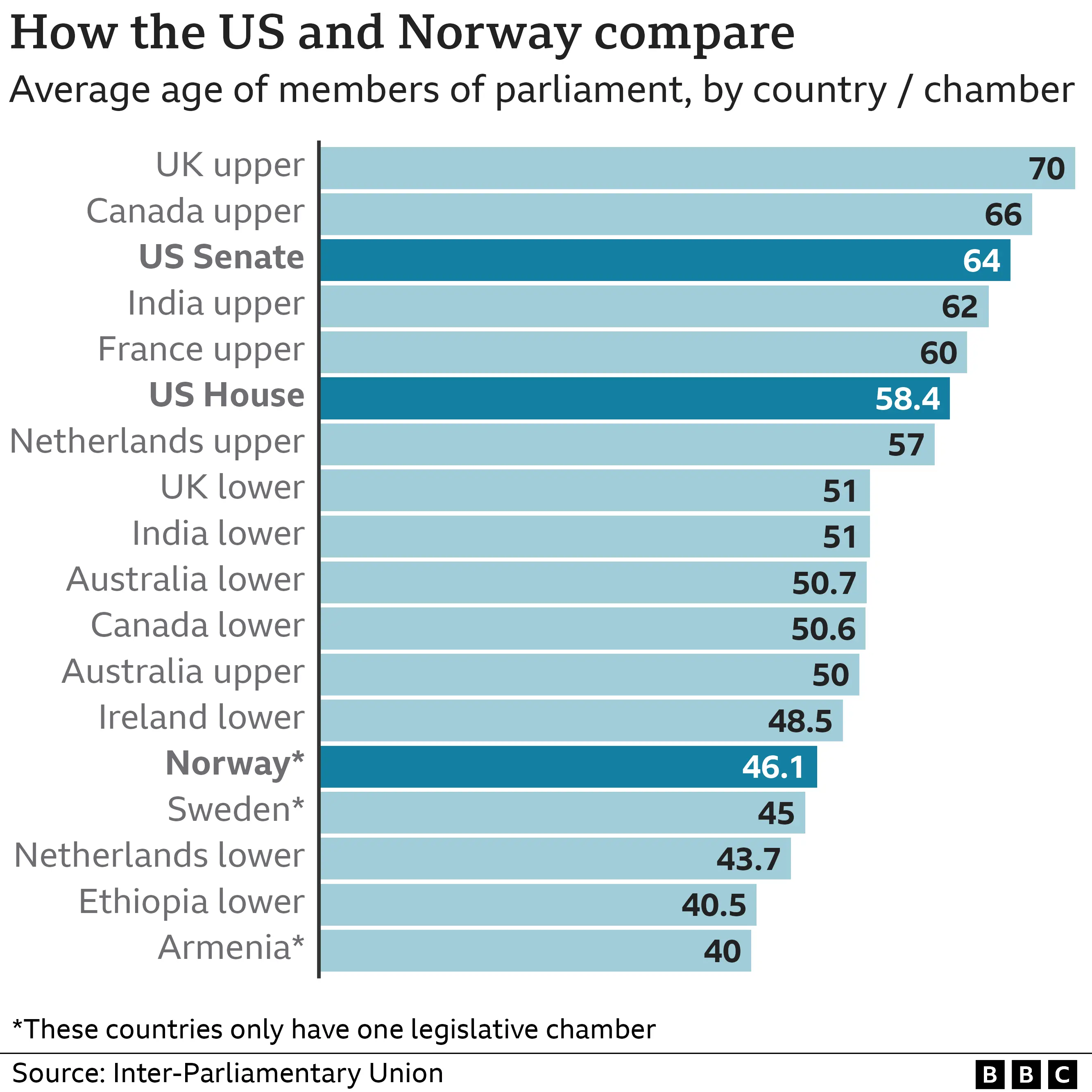

It's a similar story with average age - only the UK's House of Lords and Canada's upper chamber are "older" than the US Senate. Norway's average age is 18 years younger.

Maren Grøthe became the youngest national politician in Norway's history when she was elected to its national assembly, the Storting, aged just 20 last year.

Born just a few months before the terrorist attacks on 9/11 in 2001, she is one of 23 representatives under the age of 30, up by six since 2013.

"I really enjoy it. This is a job with great responsibilities, and I feel those responsibilities every day," Grøthe tells the BBC.

The average age in the Storting is 46 and has remained so since the end of the 1990s, because while a record number of young people are joining, they are also working longer. The oldest is 77.

Jonny Lang of the IPU which collects the global data says it's crucial that parliaments look more like the countries they represent. And having young people's perspectives leads to better policies.

Despite her young age, Grøthe had already served two years as a local politician in her home municipality when she was elected to the national assembly.

She has a wide range of tasks. A recent week began with a parliamentary committee trip to Germany and ended with her back home to attend the opening of a new football pitch outside Trondheim in central Norway where she lives with her boyfriend.

The workdays are long, and the business trips are many. Every week she commutes to her apartment in the capital Oslo.

More on this series, Seeking A Solution

- As Americans prepare to vote we are visiting countries around the world looking for answers to challenges facing the US political system

- We are tackling subjects like an ageing Congress, gridlock in passing laws, a lack of female representation and low turnout

- Reporters in Norway, Bolivia, Finland, Australia and Switzerland will explain how these issues are handled where they live

She describes herself as an "ordinary Norwegian youth" who likes both partying with friends and hiking in the mountains. But since she was elected to the Storting, there has been far less time for such activities.

Grøthe believes that having so many young politicians in the Storting brings many advantages, with different cultures and ages better represented. "We young people have life experience, but in a different way. We need to develop policies for everyone in the country."

But what can she contribute to politics that a 55-year-old can't?

"I have completely different perspectives and knowledge on being young today. More and more young people struggle with their mental health. I have also just finished my high school education, which is useful in the education committee in the national assembly," she says.

The electoral system is one reason Norway has the world's youngest parliament, believes Ragnhild Louise Muriaas, professor of political science at the University of Bergen. Several people from the same party can be elected in the same district.

"This means that an older and well-known man may be the top candidate, but unknown, young women may be nominated for the next positions on the list and be sure to be elected," she says. In France, UK and the US it's winner takes all and parties feel they cannot "afford" to top the lists with young, inexperienced candidates.

Handout

HandoutThe youth wings of the political parties also play a part, she adds. These organisations are a strong political force, often with opinions opposing those of the parent party.

There are possible drawbacks too, says Muriaas. She is looking into whether young politicians disappear more quickly from politics. The lack of life and work experiences before being elected is another open question.

The Norway model has not been replicated in the US, but researchers at Tufts University's Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) suggest some developments in recent years may boost youth representation.

They argue that while political parties do not typically have a youth strategy, youth organisations - particularly on the Republican side - have garnered more visibility and funding. They also point out the growing adoption of electoral measures such as ranked-choice voting, where voters rank candidates based on preference, can benefit young candidates.

But because party gatekeepers often suppress young candidates, the young and civically-engaged need to be actively encouraged or financially supported to run for office, beginning at the local level, says CIRCLE fellow Sara Suzuki.

Two members of Generation Z - a Democrat and Republican apiece - will appear on midterm ballots this November for the first time. If they win, they will chip away at older generations' dominance in Congress.