War in Ukraine: Ukrainians deported to Russia beaten and mistreated

BBC

BBCThree weeks since his release, Volodymyr Khropun still looks visibly shaken by the trauma he's endured. A Red Cross volunteer, he was captured by Russian forces, and deported to Russia.

On 18 March, Volodymyr was driving a school bus to the village of Kozarovychi, about 40km (25 miles) north-west of Kyiv, to evacuate a few civilians who were stuck there amid the fighting. When he tried to convince Russian soldiers to let him pass their checkpoint, they detained him.

For the first few days he was kept in the basement of a factory of a village nearby, along with other civilians, 40 people in a 28 sq m (300 sq ft) room.

"We were beaten with rifles, punched, and kicked. They blindfolded me and tied my hands with duct tape. They used Tasers and kept asking for information about the military," Volodymyr said.

"One of the soldiers was very young, almost a child. He used Tasers on people's necks, faces, knees. It's like he was having fun."

After being held for nearly a week in Ukraine, they were transported to Belarus.

"They thought we couldn't see, but I saw the villages we were passing, Ivankiv, Chernobyl and then I saw us crossing the border," he said.

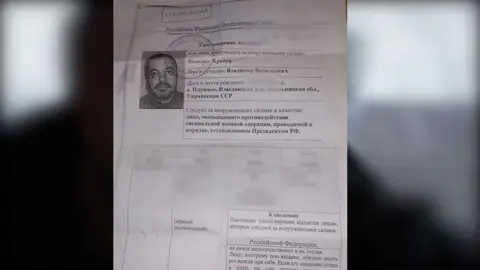

In Belarus, they were given an identity document. It says it is issued by the military of the Russian Federation and describes Volodymyr's place of birth as the "Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic". It is how Ukraine was known prior to the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, before it became an independent country. It is a sign of Russia's ambitions in the region.

From Belarus, Volodymyr says, they were taken to a prison in Russia.

"The torture continued. They humiliated us, made us kneel and forced us into uncomfortable positions. If we looked into their eyes, we were beaten. If we did something slowly we were beaten. They treated us like animals," he said.

One evening Volodymyr counted 72 other people in detention with him. But he could hear there were more.

"We tried to support each other. Some days we couldn't believe this was all happening. It felt like we had been transported to the 16th Century from the 21st Century," he said.

Two weeks into detention, on 7 April, Volodymyr was taken from prison. He and three female Ukrainian civilians from another detention centre were transported by air to Crimea, which was annexed by Russia from Ukraine in 2014.

The women told Volodymyr they had also been beaten. They didn't understand where they were being taken to, but frequently heard the soldiers use the word "exchange."

From Crimea they were taken by road to a point 32 km (20 miles) outside Zaporizhzhia, and allowed to walk across a bridge to Ukrainian-controlled territory. The exchange of military prisoners of war from both sides took place before Ukrainian civilians were allowed to walk over. It was 9 April. It had taken them two days to make the journey.

Volodymyr struggles to describe how he felt, but he wants the world to hear his story.

"The fact that Ukrainian civilians are being held there [in Russia] is a 100% true."

In the prison, Volodymyr heard that people from the Chernobyl nuclear site were being held in a room next door.

It is unclear who exactly the men in the prison were, but 169 Ukrainian National Guard responsible for securing Chernobyl are missing. They were first held in detention in the basement of the nuclear site for weeks when it was occupied by Russian troops.

Valeriy Semonov, one of the engineers at Chernobyl, said that when Russian forces withdrew at the end of March, they took the guards along.

In a village nearby lives the family of one of the missing men. Their identities are being hidden to protect them.

On duty in Chernobyl, the serviceman had called his wife on the first day of the invasion, when the nuclear site was taken, to tell her to leave their village.

She took her parents and their young son and went to the city of Lviv in western Ukraine.

From 24 February to 9 March, she was able to talk to her husband on his mobile phone.

"He would not share much on the phone. He would just say, 'We're OK'. He would tell me to not worry about him," she said. "Then they lost power, so we couldn't connect to his phone."

She still managed to talk to him a few more times over a landline phone at the site.

"The last time I spoke to my husband was on 31 March, on the day they were forcefully taken from Chernobyl. He told me, 'I'm OK physically, but emotionally it's very hard.' I could understand from his voice that he was very worried."

Her son asks about his father all the time.

"I tell him he's at work, but he's very scared. He's worried I will disappear too, and keeps following me around everywhere, to work, to the shops," she said. "It's very tough for us. I just want Russia to release my husband."

Ukraine's interior ministry has told her he is being held in Russia.

Married for six-and-a-half years, she said he was always there for her and that he loved his job.

The BBC has spoken to the families of more than a dozen people who have been taken hostage by Russian troops.

Only a few have returned. The majority are still missing, like Yuliia Payevska. Her husband Vadym told us she was captured by Russian forces on 14 March when she was working as a paramedic in Mariupol, helping evacuate injured soldiers and civilians.

A propaganda video featuring her was carried by some pro-Kremlin Russian TV channels, which is how he found out she's in Russian captivity. He believes she has been taken to Russia.

The Kremlin insists Ukrainian citizens are going to Russia willingly.

"I don't want to respond to these huge liars," said Iryna Venediktova, Ukraine's prosecutor general.

"There are at least 6,000 civilians who we can identify who have been deported, and from information in mass media in Russia, they say they have taken a million Ukrainians."

She said there have been instances of children being separated from their parents, and that almost everyone who has returned on a prisoner exchange has told them they were tortured and beaten.

As the war rages in Ukraine's south and east, every day there are new reports of people being forcibly deported to Russia.

Additional reporting by Imogen Anderson, Daria Sipigina and Anastasiia Levchenko.

War in Ukraine: More coverage

- DONBAS: Facing the Russian Army on the front line

- UKRAINE: Why India is buying more Russian oil

- ODESA ATTACK: 'My world was destroyed by a Russian missile'

- READ MORE: Full coverage of the crisis