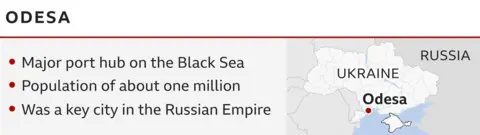

Ukraine: Elegant Odesa is transformed by efforts to deter Russians

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile Russian advances across Ukraine have slowed in recent days, people in the strategic port city of Odesa are preparing for an expected and imminent Russian attack.

Decision-time is fast approaching in Odesa. As Russian warships circle off the coast, air-raid sirens wail over the cobbled streets, and Russian ground forces seek to advance west along the shores of the Black Sea, civilians in this historic, famously cosmopolitan port city are facing the same hard and urgent choices that millions of other Ukrainians have already confronted.

Some residents have left Odesa, heading west towards the nearby border with Moldova or taking a crowded train north to Lviv. The city's elegant boulevards, with their cafes, trams, and theatres, now stand mostly empty and littered with tank traps, while protective sandbags crowd around some of the most famous monuments.

But like many Odesans, Valentin Kartashova is staying put - for now. She runs a state orphanage, looking after 90 children, including both newborns and 18 others with severe disabilities.

"These children are dependent on oxygen, on respiratory support to keep them alive. I've had many offers of help from abroad. But they want to meet us at the border. I can't take these children by train or car. How can I move them from here? Must I leave them? Must I abandon them? And only take the healthy ones?" asks Kartashova, shaking her head.

She's prepared a cellar in the orphanage compound, with supplies to last a week or more, and has decided the children will be safer staying in Odesa, unless they come under direct fire.

A few miles closer to the city centre, Olga Pavlova has also reached a similar decision.

"I'm afraid - and not only me. I think other people are just as afraid of the situation. But we'll stay here. We love our city and we'll stay. I've become a volunteer. Who else will feed the animals?" says Pavlova, a veterinarian scientist who works at Odesa's municipal zoo.

Hundreds of families have already left pets at the zoo before fleeing, but almost all the staff have decided to remain at work.

"We've decided it is better to stay put. The animals are our responsibility. We'll win this war soon, I believe. People will return and we need to make sure the zoo is still here, and the theatres, the libraries. We need to guard all that - to protect our culture," says the zoo's director, Igor Beliakov. He explains that some of the more nervous animals - a 43-year-old African elephant known as Daisy, several bears, and zebras - are being kept inside in case the sound of explosions makes them panic.

Playing their regular game of chess in a park near the city's Russian Orthodox cathedral, in sub-zero temperatures, two ethnic Russian pensioners, Alexander Nikrasov and Nikolai Ivanov, describe the invasion as "worse than the Nazis", who occupied Odesa during World War Two.

"At least the Germans didn't destroy the city when they left Odesa, but now there's every chance it will be destroyed," says Ivanov.

"Mykolaiv [a city under Russian attack, to the east] is already suffering for defending us. Of course, the war will come here. People are dying in their thousands and for what? Because Putin wants to take something from us?" asks Nikrasov, brandishing a walking stick which he calls, "my only weapon."

Speaking by phone from Italy, one of Odesa's most renowned Russian-speaking poets, Boris Khersonsky, says he is "not a refugee", but left the city a few days earlier after receiving a literary invitation.

"It's a really difficult decision. What do you have to keep you in Odesa? What is waiting for you abroad?" says Khersonsky, adding that he plans to return imminently, assuming the city remains under Ukrainian control.

"If the city is under Putin's rule, I won't return. If Putin succeeds in capturing Mykolaiv then he has a straight path to Odesa. It's always been a volatile city with a big cultural heritage. Over the years, many writers - who are the glory of Odesa - have left. Odesa can give birth to talent, but very often it doesn't take care of it," he says.

As in so much of Ukraine, many people are volunteering to join the local defence forces.

"I love my country. I want to live in a free country. Russian is my language, but now Russia is the enemy. Maybe it's a surprise, but maybe it was expected," says Ruslan Prihodka, who usually works in a chemist, but is now learning to assemble an AK47 in a classroom near the city centre.

"I don't know how to fight yet. But we'll have to do our best. Maybe there's something wrong in Putin's head," says Dima, a construction worker, standing nearby.

During one air raid, volunteers working at a food-collection centre near the city's grand old opera house rushed to the basement, where a local singer brought out a guitar to play Ukrainian folk songs.

"Having watched how Russian forces have already destroyed other historic towns like Kharkiv, I have no hope that our Russian heritage will spare us from their bombs," says Alexei Kostrzhitski, an IT expert now serving as a captain in a local defence group.

"Mariupol and Kharkiv are very pro-Russian cities," adds a young city councillor, Petro Obukhov. "Most citizens here speak in Russian not Ukrainian. And still Putin bombs them. It makes no sense but still I hope he will not bomb us."