Under threat of Russian bombs, Lviv hides away its priceless heritage

BBC

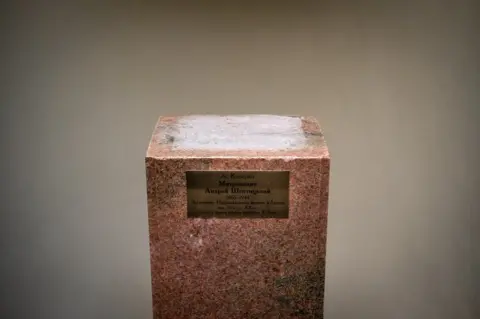

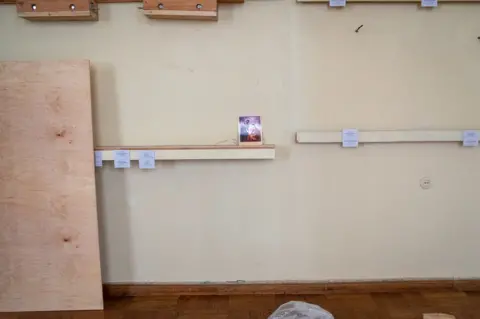

BBCIn one room of the National Museum of Lviv, an enormous scaffold is bare. In another, brackets hang loosely from the walls. Plinths sit empty along the corridors and wooden pallets and cardboard boxes are strewn on the floors. The staff used whatever they could to pack away the museum's priceless artefacts in a hurry.

As Russian shelling has devastated other parts of Ukraine, the picturesque western city of Lviv has been left untouched, so far. But it is bracing for war. Some preparations you can see in the open - the checkpoints on main roads and the soldiers on the streets - but some are taking place behind closed doors.

In Lviv's galleries, museums and churches, a huge operation is under way to safeguard the city's cultural heritage. Thousands of artworks and artefacts have been carefully removed and taken to secret underground locations, or down to basement storage rooms.

Ihor Kozhan, the director of the National Museum of Lviv - the largest art museum in Ukraine - took the BBC on a tour of its now empty rooms, which looked as though they had been looted. Climate-controlled display cases, usually home to artworks, icons and manuscripts dating as far back as the 14th Century, were bare.

Nearly every one of the 1,500 artefacts on display has now been removed from the museum. The other 97% of the collection - 180,000 pieces in total - was already in storage in some form.

"Everything, everything is gone," Kozhan said.

Despite overseeing the operation, Kozhan was amazed by the speed with which the 17th-century Bohorodchany Iconostasis - a grouping of religions paintings measuring 10m by 8m and one of the museum's most valuable pieces - had been dismantled by his team. It had taken six months to hang, piece by piece, he said, and less than six days to pull down from its scaffold and store away.

Constructed and painted over seven years beginning in 1698, the iconostasis represents the high watermark of the work of the icon painter Yov Kondzelevych. It has been in Lviv since 1924, then a Polish city, brought there by an archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.

It was dismantled and hidden from the Nazis in 1939, forbidden from display during the Soviet era, painstakingly restored in 2006, and now dismantled once more.

There was no plan in place for the evacuation of the museum's artefacts before the invasion began two weeks ago, Kozhan said - not even after Russia began months ago to mass troops along Ukraine's borders.

"There was no plan because no one could imagine this would happen," he said. "We had no plan at all - not before the war, not even in December. You must understand, we did not believe it could come to this."

Around Lviv, cultural and religious officials are running complex operations to wrap up statues, seal off stained glass windows and spirit away sacred artefacts.

In the city's main square, fountains with sculptures of Greek gods and goddesses have been wrapped in flame-retardant fabric and covered with scaffolds to protect them from falling masonry.

"At first it was a bit chaotic but it has become more organised," said Liliya Onischenko, the head of Lviv's city council heritage protection office.

"We are photographing everything before we take it away and we are photographing all the pieces in their hidden places," she said

Onischenko said the priority was protecting the stained glass windows in the city's historical old town, a Unesco world heritage site whose architecture was built over centuries by different nationalities - Poles, Austrians, Hungarians, Germans, Armenians - as the region changed hands.

At the Armenian cathedral, a prized 15th-Century wooden sculpture of Christ on the cross was removed for the first time since World War Two and taken to a secret, safe place.

Other artefacts besides the sculpture have been removed, the deacon, Armen Hakopian said, but he would not elaborate. "What needed to be taken out was taken out," he said, with a smile.

The windows along the side of the 850-year-old Armenian cathedral are plain, because the original stained glass was blown out in the 1940s by German bombing. But above, stained glass remains in the cupola and the high parts of the church.

The institutions of Lviv have had the benefit of time to prepare. And they may yet escape the violence. But there are grave fears for the cultural, religious and architectural treasures in the parts of Ukraine under attack.

There has already been significant damage. The stained glass windows and nave of the assumption cathedral in Kharkiv were damaged by Russian shelling. Russian troops have reportedly destroyed a 19th-century wooden church in the village of Viazivka in Zhytomyr. And a museum in Ivankiv, north of Kyiv, was razed, destroying 25 works by the Ukrainian folk artist Maria Prymachenko.

Ihor Kozhan, the national museum director, said he feared that destroying Ukraine's cultural fabric was part of Russia's goal, and he feared greatly for Lviv.

"If the same damage is done here as in Kharkiv, Mariupol, it would be a terrible tragedy," he said.

"This is a place of historical memory. The museums here hold the history of the nation. They give us an understanding of who we were, who we are, and who we will be.

"Russia wants to destroy that."

The job of emptying the national museum was virtually complete by Wednesday - only a few cardboard boxes of manuscripts were left, near the doors, alongside a sculpture lying on the floor - one of several too heavy to move that will be protected in other ways.

The artefacts that have been moved underground are on a clock - too long there without adequate climate control and they would begin to degrade, Kozhan said.

And they would not probably not survive a direct hit, he said, with a long sigh, because the bunkers are not designed to withstand powerful bombs.

"I hope we can bring them up soon," he said. "It is difficult for me to be here in these empty rooms and hallways. We could have walked the whole day here together looking at our history and our art."

Asked to estimate the total value of the museum's works, Kozhan declined.

"Of course there is no number," he said.

"If these things are destroyed they cannot be remade."

Additional reporting by Svitlana Libet. Photographs by Joel Gunter.

Correction 8 April 2022: This article has been amended after we mistakenly stated Lviv was part of Ukraine in 1924. It was in fact a Polish city at that time.