Paris attacks trial: Humdrum lives that turned to mass murder

Elisabeth de Pourquery/FranceTele/Reuters

Elisabeth de Pourquery/FranceTele/ReutersThey had happy childhoods in Brussels, Malmo or Tunis, with plenty of brothers and sisters and parents who worked hard to give them life's comforts.

The long-running Paris attacks trial heard this week how the once ordinary lives of 14 men in the dock became a mix of petty jobs and petty crime. Some went to join the war in Syria, and then became caught up in an Islamic State vengeance plot to wreak terrorist havoc in Western Europe.

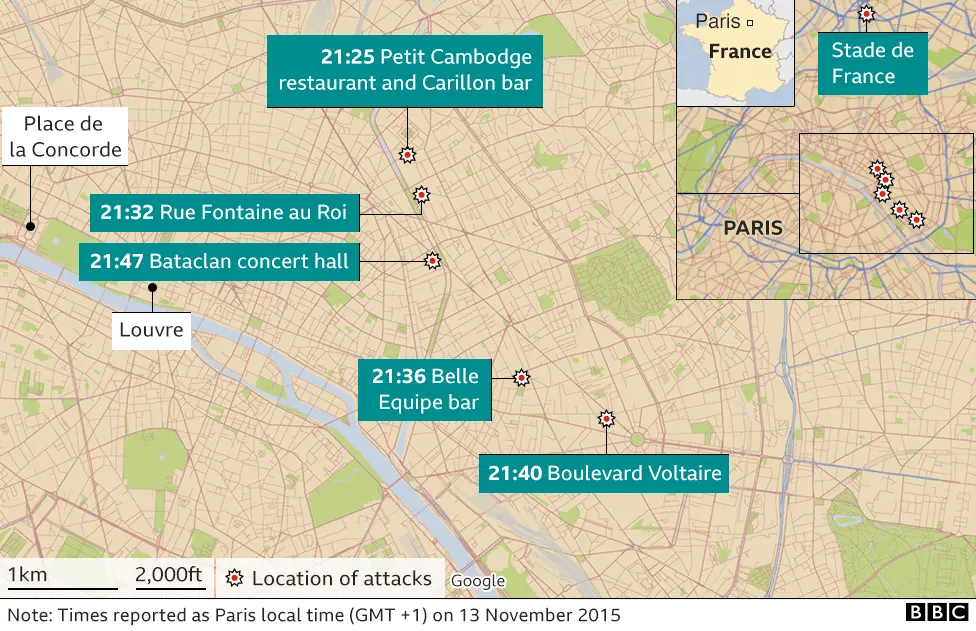

It culminated in the murder of 130 people on the night of 13 November 2015.

This is the moment in major trials in France when prosecutors and lawyers get a chance to look into the private, working - and criminal - lives of defendants. Questions on the actual charges or the men's religious beliefs were excluded by the presiding judge until January.

After weeks of painful eyewitness accounts, it is the first time since the trial began in September that the spotlight has been on the accused, and their voices help build a picture of the world from which they emerged.

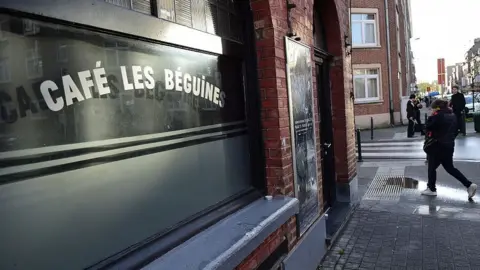

A key place in this world was the Molenbeek neighbourhood of Brussels, and in particular the Les Béguines café there, run by Brahim Abdeslam.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBrahim Abdeslam was one of the café terrace gunmen in November 2015.

He blew himself up at the Comptoir Voltaire. He was also the brother of Salah Abdeslam, the alleged "10th man" in the Paris attacks and best-known of the defendants.

Speaking of his childhood on Tuesday, Salah Abdeslam, 32, cut a different figure from the aggressively unrepentant side that he has shown so far in the trial. He even raised a few mild laughs in the courtroom.

Born in Brussels to Moroccan parents, and with French nationality, he described himself as "quiet - a nice guy". "I was popular with the teachers… good in certain subjects. I studied hard. I gave my all. I was ambitious."

He took a diploma in electrical mechanics and started work, like his father, at the Brussels tram company. But after a year and a half he was fired.

"Why were you fired?" asked the presiding judge.

"Because I was in prison."

At the end of 2010, Salah Abdeslam had taken part in a botched robbery with his friend Abdelhamid Abaaoud - the same Abaaoud who would become the ringleader of the Paris attacks.

"I was born and grew up in Belgium. I went to state school. I lived as I was taught to live in the West. Like everyone else, I wanted to marry and have children," he told the court.

"But I put all that to one side the moment I decided to invest myself in another project."

What other project, asked the judge. "The things I am accused of now."

Another habitué of Les Béguines in Molenbeek was Mohamed Abrini, 36.

He is accused of ferrying the Paris jihadists from Brussels on the eve of the attacks. He is also believed to be the "man in the hat" who failed to blow himself up in the deadly attack on Brussels airport in March 2016.

AFP/Getty

AFP/GettyOne of seven children of a Moroccan-born builder who "earned a good wage - we were neither rich nor poor", he had a first conviction (of six) at 17 for stealing a car.

Then came a succession of odd jobs, but he was also a compulsive gambler. He planned to marry, but when a younger brother was killed in Syria, he vowed to go there too.

"Did you not wish to repay your parents for their love and encouragement?" asked the judge.

"Naturally they were disappointed. I'd have liked to make my father proud. Our parents did all they could to make sure we succeeded in life. I was dragged down by the neighbourhood."

"And yet your elder brother, who also grew up there - he did well in life."

"If you add up those who failed and those who succeeded, it's about 80-20. I am one of those who did not make a success."

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty Images

Hamza Attou, 27, also frequented Les Béguines.

The youngest of six children born to Belgian-Moroccan parents, he said he had a good childhood but after leaving school developed a cannabis habit. To pay for it, he began to deal.

"That's how I lived. I sold cannabis resin. I know it's an offence. I'm not proud of it. But I couldn't see myself robbing people or mugging them."

He is accused of driving from Brussels to pick up Salah Abdeslam late on the night of the attacks.

One of three defendants who are not in custody for the trial, he was nonetheless found to have occasionally violated the terms of his conditional release, notably by staying out late at night.

AFP

AFP"Do you not see you could go to prison for that?" asked the judge.

"Often in my life I act and then I reflect. That's how I ended up where I am now," he said.

Another Belgian of Moroccan origin, Mohamed Bakkali, 34, grew up one of six children "in a nice house and garden".

"It was a united family. I played football at a local club and went to the municipal library. I read a lot."

After leaving school he worked with his father at a garage. "That's when I began to learn Arabic, to speak to the customers." At home they spoke Berber.

But then he began dealing in counterfeit goods: "Clothes, trainers, watches, perfume - I sold it all."

Bakkali is accused of helping with the logistics of the attacks. He is serving a prison term for a similar role in the so-called Thalys attack of August 2015.

In jail, where like other defendants he is kept in isolation, he has taken up studies in sociology.

"Originally I wanted to do ethnology, to discover the Berber people and my roots," he said. "But then I discovered sociology. It has helped me understand the complexity of things. I am learning about the things I no longer have - social relations."

While most of the accused have Belgian or French nationality, four grew up in Sweden, Tunisia, Algeria and Pakistan. They went to Syria to join Islamic State militants and then crossed Europe in 2015.

Osama Krayem, 29, was born in Malmo, the son of a Syrian father and a Palestinian mother.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt 12 he appeared playing football in a Swedish television documentary on the successes of the immigrant experience.

"So you were given as an example of integration?" asked the judge.

"Possibly."

"You felt you were well integrated at that point?"

No, he replied: "I lived in a neighbourhood where there was not a single Swede."

Pakistani Muhamed Usman lost his farmer father when he was very young.

He remembered enjoying cricket as a boy, but could not tell how many years he spent working in the fields and how many studying at a madrassa. "I don't know at what age I stopped my studies. In my people we do not celebrate birthdays."

Which is a problem, because no-one can determine his age today.

Fake papers that he was carrying when arrested in Greece say he was born in 1981, but an identity card sent by Pakistani police gives his year of birth as 1993.

The judge said he looked far too old to be just 28. "I know I do not look my age. It is because of being in isolation," he said.

The religious motivation of the accused was not explored, nor were the steps they took that brought them to where they are.

All that must await another chapter in the trial.