Paris attacks: Historic day of reckoning for night of terror

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn the evening of Friday 13 November 2015, Theresa Cede - an Austrian mother of two living in Paris - had invited out her friend Stéphane to celebrate his 40th birthday. Her present: two tickets for Californian band Eagles of Death Metal at the Bataclan concert hall.

They were standing near the entrance next to the concessions stall when three gunmen burst in at 21:47, killing indiscriminately. She was saved by a man who was shot and fell next to her.

"I owe him my life. I was shielded by his body, while the shooting continued around us," she said.

At around 22:00 a policeman and his driver fired at one of the gunmen on stage with a victim, causing the attacker's jacket to explode. Shortly after, the two remaining jihadists retreated in a corridor on the top level of the Bataclan, taking hostages. Theresa and Stéphane were eventually evacuated shortly before the final assault at 00:20.

Nearly six years later it is a moment of reckoning for the thousands of people who, directly or indirectly, found themselves caught up in France's worst ever night of terrorism.

Opening on Wednesday and set to continue until next May is a trial hallmarked to go down in history.

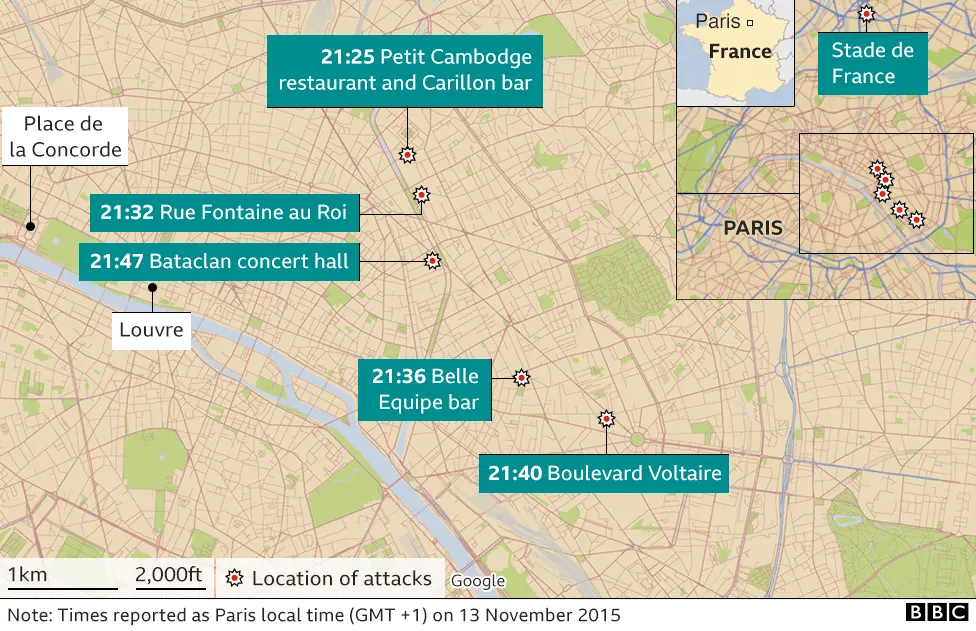

In a specially constructed courtroom in the historic Palais de Justice on the Île de la Cité, 20 men will be judged for the jihadist Islamic State (IS) plot that led to 130 dead and hundreds of wounded that night, not just at the Bataclan but also at the Stade de France and on the café-terraces of the 10th and 11th arrondissements.

Among the defendants is the last survivor of the 10-man squad who set out on the evening of the attack.

Salah Abdeslam, 31, was also supposed to blow himself up, but instead he threw away his suicide belt and fled back to Brussels where he was arrested months later. From prison he has said very little, but his questioning will be a key point of the trial.

Theresa Cede is one of nearly 1,800 civil plaintiffs - mainly survivors and relatives of the dead - who have the right to tell their story before the court. Their memories will take up five weeks of hearings.

While Theresa has not yet decided to speak herself, she will attend to give support to those who do.

Nearly six years of investigations conducted in 19 countries have resulted in a mountain of evidence. The justice ministry says that the 47,000 depositions and statements amount to 542 volumes which stacked up would reach 53 metres in height.

The aim of the trial is not just to establish the guilt or innocence of the 20 accused, it is also to document the origins, planning and execution of the 13 November conspiracy:

- from its conception in the higher ranks of Islamic State in Raqqa, Syria

- to the despatch of secret operatives hidden among the ranks of migrants entering Europe from Turkey and Greece in 2015

- to the logistical details worked out from the Molenbeek quarter of Brussels

- and then the actions of the three attack squads known as "commandos" on the night of the killings.

To accommodate the large numbers of lawyers, plaintiffs, journalists and members of the public, it was decided to convert an entire gallery of the 19th-Century Palais de Justice.

The gallery now contains a 45m (147ft) by 15m wood-panelled salle, with seating for 600, which will be the main courtroom, as well as two other principal rooms for press and relatives.

With other smaller rooms also fitted with projection screens, there is space for up to 2,000 people - though after the opening it is estimated only a fraction of that number will attend.

The whole trial will be filmed for posterity, as was the smaller Charlie Hebdo trial last year, and an online radio feed will be available to survivors and other plaintiffs so they can keep abreast of developments.

Built at a cost of €7m (£6m), the new courtroom will be used over the next two years for other terror trials - such as the one arising from the Nice lorry attack of July 2016. The scale of the enterprise is meant to impress on the French the solemnity and historic nature of the trial.

In the words of Le Monde newspaper, "It is the ultimate response of democratic nations to the challenge of terrorism: the law; all the law; nothing but the law."

Among the accused, attention will inevitably focus on Salah Abdeslam. This is because in the established account of 13 November, he was the one who was supposed to die but didn't.

A childhood friend of Abdelhamid Abaaoud (the leader of the commando group who died in a shoot-out in Saint-Denis on 18 November), he allegedly played an important role ferrying the newly arrived jihadists by car from Germany and Hungary to Brussels.

Belgian/French police

Belgian/French policeHe is said to have rented cars and hotel rooms in Paris, and then driven the three suicide-bombers to the Stade de France.

But there is still uncertainty over what happened next. Leaving his car in the 18th arrondissement, he dumped the suicide vest in the suburb of Montrouge and after calling a friend in Brussels was picked up and driven back to Belgium.

A few months later, just before the deadly Brussels suicide attacks of March 2016 - carried out by the same IS militant cell set up by Abaaoud - Salah Abdeslam was arrested in Molenbeek.

PA

PAHe told police that he had a change of heart and that was why he did not blow himself up. But the investigation established that the suicide vest was in fact defective - opening the possibility that he tried but failed to complete his mission.

Of the other 19 defendants, six are absent and five of them are presumed dead: senior IS men probably killed in US drone strikes. The sixth is in prison in Turkey. Of the others some are accused of helping the gang without necessarily knowing the extent of the conspiracy.

But others, it is alleged, were important figures, and some may themselves have been intended as suicide-bombers on the night of the attack.

One of the more intriguing items of evidence in the case is a computer abandoned by the gang and found in Brussels following the March 2016 attacks there.

This included a schedule setting out the 13 November attacks, including the three Paris targets - but also two more: Schiphol airport in the Netherlands and "metro".

One theory is that a fourth squad - including two of the accused at the trial - may have been ordered to attack Schiphol.

There is also the possibility that Salah Abdeslam himself may have been told to attack the Paris metro, at the point where he abandoned his car. This would explain why the IS propaganda machine included a non-existent attack on the 18th arrondissement in its list of "victories" that night.

For Theresa Cede, the first year after the attacks was spent compiling all the information she could find about what had happened at the Bataclan. "I had to find people who were there; I had to hear their stories; I had this absolute need to understand," she says.

"I am naturally an outgoing and resilient person. I had a job, a husband and two kids. My absolute priority at the start was that I would not let it have an impact on my family. But that was wishful thinking."

Theresa Cede

Theresa CedeFrom the start she says she had to change which side of the bed she slept on, because of spending two and a half hours next to her dead protector.

"Things suddenly bubble up," she says. "When one of my sons had a birthday the sulphur smell of the candles set me off. When he went to a show with his school, the sight of the theatre with those velvet seats was another trigger."

For Theresa, as for many others. the weeks ahead will be tough, as the memories are brought out once again under the public gaze. Tough, she says, but necessary.

"The trial is an important step. It has to be gone through. I am not sure it will bring closure or solace. But it is part of the process." s