Italy's plummeting birth rate worsened by pandemic

BBC

BBCFor Micaela Pisanu and Pino Cadinu, the vines on their Sardinian hillside require an investment of love and care. Rather like their plan for a baby that they, like a record number of Italian couples, have felt compelled to postpone.

The engaged Sardinian couple had planned to start a family last year. But then the pandemic hit, the bar Micaela was running closed and now they work on their small vineyard in the wildflower-filled fields above the town of Mamoiada, eking out a living and putting off their hopes of having a baby.

"It's very hard when you want to have a child but don't feel able to because of uncertainty about your future," Micaela says. "Things are so insecure that if I find work, then fall pregnant and maybe lose my job, it would be unmanageable. People will now think 20 times before having a baby."

Births outnumbered by deaths

Their difficulty, felt across this country, is crippling Italy's birth rate, now at the lowest since its unification in 1861. It's declined every year since the 2008 financial crisis.

But Covid-19 has accentuated the fall, with its devastating financial effect and its impact on the divorce rate, which has risen in part, it's thought, due to couples being stuck at home together.

At just over 400,000 last year, Italy's births were hugely outnumbered by deaths, leading the population to drop by 384,000: equivalent to the city of Florence being wiped off the map.

The couple live with Pino's mother, one of the post-war baby-boomer generation that Pino says could manage a job and a family. "But for ours, buying a house, owning land and still having enough money to give children opportunities is impossible."

It's a problem that much of Europe is facing and could threaten economic growth, pension systems and public services.

But Italy, with the world's second-oldest population and a long-stagnating economy that's helped drive 10% of its population to live abroad, is particularly vulnerable.

'There's not much work around'

Sardinia has the country's lowest birth rate of all: less than one child per family.

In the little town of Gadoni in the centre of the island, the school of 25 pupils has brought together year groups in the same class, since there aren't enough to be separated. In one classroom, 11 to 14-year-olds sit together for a lesson about depopulation, learning about the life they're leading.

"Where are people from here moving to?", asks the teacher Marco Marras. "Europe," says one pupil; "Australia," another.

Eleven-year-old Nicolas is in no doubt. "Lots of people have left for opportunities elsewhere, which makes sense," he says, "as there's not much work around."

His classmate Bilen has a positive spin: "It's better that we're together with the other grades because there are more of us," he says. "It would have been boring if there were just a few people from my year."

Difficult future for Sardinia

For the school, the future looks bleak. With no births in Gadoni last year and none anticipated in 2021, there's a constant risk that the school will eventually close.

Maternity wards, too, are trying to resist being shut down. When we visited one in the southern city of Carbonia, just two rather hungry newborns lay in the nursery, surrounded by empty cribs.

Last year, it fell far short of the threshold of 500 babies to stay open. And now it could close, says Debora Porrà, the mayor of a nearby town that the unit serves.

"At this rate, the estimate is that Italy would lose a quarter of its population within 30 years," she says.

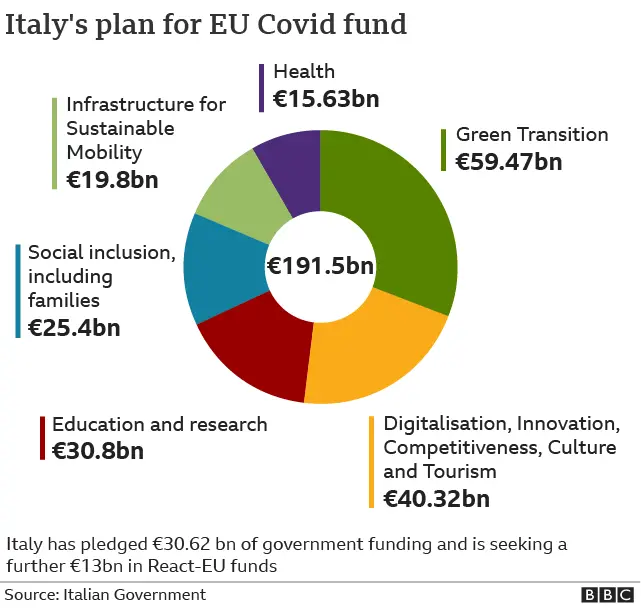

They are beginning to tackle the problem with a new "family plan" that the government will finance with EU Covid recovery funds.

It will include child benefits and investment in day care and schools. But it could be too late to turn the tide.

Reversing Italy's brain drain

The pandemic, though, has opened up another side to the story, leading an estimated 100,000 Italians who had moved abroad to return to Italy.

Some have come back to be with family, others to work from home.

In the tiny mountain hamlet of Lollove, Simone Ciferni calls his recently-opened farm and eco-hotel, named Lollovers, a "digital detox destination". He studied and worked in the UK, US and South Africa, before deciding to return to his home village of 13 inhabitants, where most of the stone houses lie abandoned.

"It's the only way to save this hamlet," he believes. "I thought it could die if I didn't come back to do something here. In Italy we have more than 5,000 villages like Lollove that could disappear within the next 10 years."

As he feeds his goats, he admits he was tempted to stay abroad. "We need to discover the world to catch all the interesting stuff - but then we must come back to preserve our traditions."

It's a partial reverse of the brain drain, but a drop in the ocean for a country in the grip of a demographic crisis.

The traditional Italian image of large families is one outdated stereotype this country could do with recreating.