Is Russia targeting CIA spies with secret weapons?

BBC

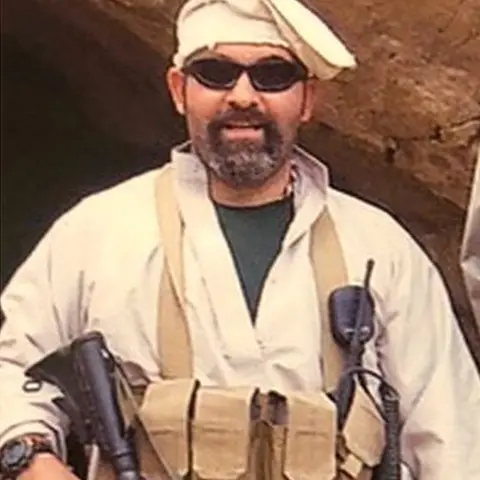

BBCMarc Polymeropoulos woke up in his hotel room with his head spinning and ears ringing. "I felt like I was going to vomit. I couldn't stand up. I was falling over," he recalls. "I have been shot at numerous times and this was the most terrifying experience in my life."

Polymeropoulos had spent years in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan as a senior officer of the CIA fighting America's war on terrorism. But that night in Moscow he believes he was targeted by a secret, microwave weapon.

After Russia's interference in the 2016 US presidential election, CIA leadership issued a "call to arms" and redeployed battle-hardened officers like Polymeropoulos to push back.

He would eventually become acting chief of clandestine operations in Europe and Eurasia, working with allies to expose Moscow's activity, including the 2018 poisoning of former Russian spy Sergei Skripal in Salisbury, England.

In December 2017 he visited Moscow, but not undercover. He wanted to use a regular "liaison" meeting between Russian and US spies to see the country for himself. He was not there, he insists, for any clandestine activity. The Russians had not been keen on him coming, but acquiesced.

It was early on during the trip that he fell ill. On his return to the US the vertigo went, but other symptoms persisted to this day. "I've had a migraine headache for three straight years. It has never gone away," he told the BBC. He was unable to work a full day and took months off, starting a long medical journey.

His suspicions arose because, from 2016, diplomats in Havana, Cuba, reported similar symptoms - as did some Canadians.

Sometimes it was the sudden onset of a loud noise leading to intense pain, while others felt pressure on the head leading to dizziness and vertigo. The sensations seemed to come from a particular direction in a specific location. This became known as "Havana syndrome".

What caused 'Havana syndrome'?

Getty Images

Getty Images"What happened to US diplomats in Cuba, happened to me in Moscow," he believes.

But getting to the bottom of Havana syndrome has not been straightforward. The symptoms presented themselves differently in different people. Some speculated cases were unconnected or the result of a psychological illness.

The first thorough assessment came from the US National Academies of Sciences in December 2020. Even though the clinical information was often fragmentary, a committee concluded symptoms were "consistent with the effects of directed, pulsed radio frequency energy", dismissing other possibilities including poisoning or a psychological cause.

"We did find that a subset of individuals shared some very unusual and distinct clinical findings at the onset of their illnesses, and it was these findings that led us to our judgment," said Prof David A Relman of Stanford University, who chaired the panel. It did not conclude whether the pulse was deployed as a weapon or who was behind the attacks, he told the BBC, because that was beyond the committee's remit.

When Polymeropoulos was initially screened by CIA medical officials he was told his symptoms were slightly different from those in Havana and they dismissed any link, leaving him feeling let down. He attributes differences to evidence that people are affected in different ways, and the possibility that what was used on people evolved. A spokesperson for the agency told the BBC the "CIA's first priority has been and continues to be the welfare of all of our officers".

Other incidents reported beyond Cuba

After being forced to retire due to ill health in 2019, Polymeropoulos decided to go public, to bring attention to the issue and try to secure treatment at a specialist hospital, which was eventually agreed.

He says the operational side of the CIA took the issue more seriously once it became clear he was not the only potential victim.

Reports have pointed to up to half a dozen other officials being affected and cases continuing. "It's happening to several other senior agency officials," Polymeropoulos says. "And some of the officers who have been subsequently affected seem to have been involved in some way in this pushback against the Russians. You have officers who are suffering in silence."

Some incidents are reported to have taken place in countries other than Cuba or Russia, including China. GQ magazine, which first reported on the Polymeropoulos case, said a senior CIA official was affected on a 2019 visit to Australia (later confirmed by Australian media). Others were affected in Poland and Georgia.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA White House official is also reported as feeling symptoms, including pressure in the head, while in a London hotel room in August 2019 - an event that British security officials are aware of, although it is unclear what exactly took place. There has been contact between London and Washington on the issue, although the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office told the BBC it was not aware of any of its own staff being affected.

One former UK intelligence official says any proof of Russian intent would be a "game changer".

Is there evidence of Russian involvement?

Media reports in the wake of the initial Havana incidents suggested classified evidence - including intercepted communications - pointing to Russia. More recently, it has been reported that the US intelligence community used mobile phone data to locate Russian intelligence officers in proximity to CIA officers affected in some locations.

"That of course is a very interesting circumstantial case that certainly warrants additional attention," Polymeropoulos says, adding that his allegations are based on public information rather than knowledge of classified investigations after he left.

None of that has proved conclusive enough for the US government to make a formal accusation.

One possibility is that the damage to individuals was a side-effect of some kind of tool used to collect intelligence by bombarding electronic devices with microwaves to elicit information - a practice that began in the Cold War.

"The Russian security services used to flood the US embassy in Moscow with concentrated microwaves and electronic pulses," says John Sipher, a former CIA officer who worked on Russia. He says Russia even had vans that could drive around a city to target individuals.

He believes Moscow was responsible for the recent harm to CIA officers, although he is unsure of the exact motive. Another former CIA officer who served in Moscow also said he believed the Russians had used a directed energy attack, but could not be sure whether it was designed to cause harm, or whether the Russians simply did not care that harm was caused as a by-product of whatever else they were doing.

Polymeropoulos says his original presumption was of some kind of intelligence collection. But the evidence, which he accepts is often circumstantial, has left him believing that the Russians used an "offensive weapon" to deliberately hurt people.

Is it plausible?

One theory is that, in Havana, Russia wanted to disrupt any improvement in relations between the US and Cuba - traditionally a close ally of Moscow - and then expanded its use to go after intelligence officers identified as working against them, like Polymeropoulos. This would take them out of action, eat up resources and make it harder for the CIA to operate.

But this would go against an unspoken agreement that spy services do not target opposing personnel for physical harm. However, former CIA and MI6 officers point to the fact that the Russians have used a form of radioactive spy dust to track their movements in Russia, which posed risks to health.

Polymeropoulos also argues Russia under President Vladimir Putin has been willing to push boundaries - for instance using nerve agent in Salisbury. "It's certainly an escalation, but it's not out of the norm for how the Russians really messed with our personnel," he says.

In response, the Russian Foreign Ministry referred the BBC to comments in the wake of the US National Academies of Sciences report, which said: "We don't have any information about Russia having 'directed microwave weapons' or of incidences of the use of such a weapon. Such provocative, baseless speculation and fanciful hypotheses can't really be considered a serious matter for comment."

Polymeropoulos wants Congressional committees to investigate. Some senators have taken up the issue.

The scientist who led the official inquiry also wants more monitoring. "Not nearly enough has been done," Prof Relman told the BBC, saying previous efforts had been hindered by the complexity of the illness, the challenge of identifying a cause, as well as geopolitics.

The new Biden administration has announced a review of Russia's "aggressive actions" and incoming Secretary of State Antony Blinken committed during his confirmation to sharing more information about "Havana syndrome". He also promised "accountability" if a state actor was responsible. New CIA director Bill Burns, a former ambassador to Russia, may also take a close interest.

If it is proven that Russia used a microwave weapon against US officials, the consequences could be explosive. But, even if it were true, finding sufficient evidence to be confident in making a public accusation may prove difficult, leaving the issue unresolved.

For Polymeropoulos, the truth is important even if it will not stop what he has to live with every day.

"I'd rather I was shot. I'd rather there was an overt hole in my body that I knew that we could try to fix, as opposed to what's happening now."