K2: 'Savage Mountain' beckons for unprecedented winter climb

Alex Gavan

Alex GavanTwo European mountaineers embark this week on a bitterly cold, week-long trek to reach base camp on the world's second highest mountain, in a bid to achieve something that no human has ever done before.

Romanian Alex Gavan, 38, and Italian Tamara Lunger, 34, are aiming to claim one of the last great challenges in the world of high-altitude mountaineering: the winter summit of K2. They will not be alone.

At least 24 others, most of them Europeans, will try to do the same, prompting warnings that too many climbers will be risking their lives on one of the world's deadliest peaks.

"It's an extraordinarily rough landscape," Gavan told the BBC in his Bucharest home, surrounded by books and climbing gear.

So unforgiving are the conditions on K2, part of the Karakoram Range that straddles the Pakistan-China border, that it has long been referred to as The Savage Mountain. It was a name that stuck after US mountaineer George Bell said of his own attempt in 1953: "It is a savage mountain that tries to kill you."

"Because of the strong winds the mountain will be almost empty of snow," says Gavan, who is of slight build but is an intense character. "It will be a terrain of rock and ice."

Why the winter climb is so dangerous

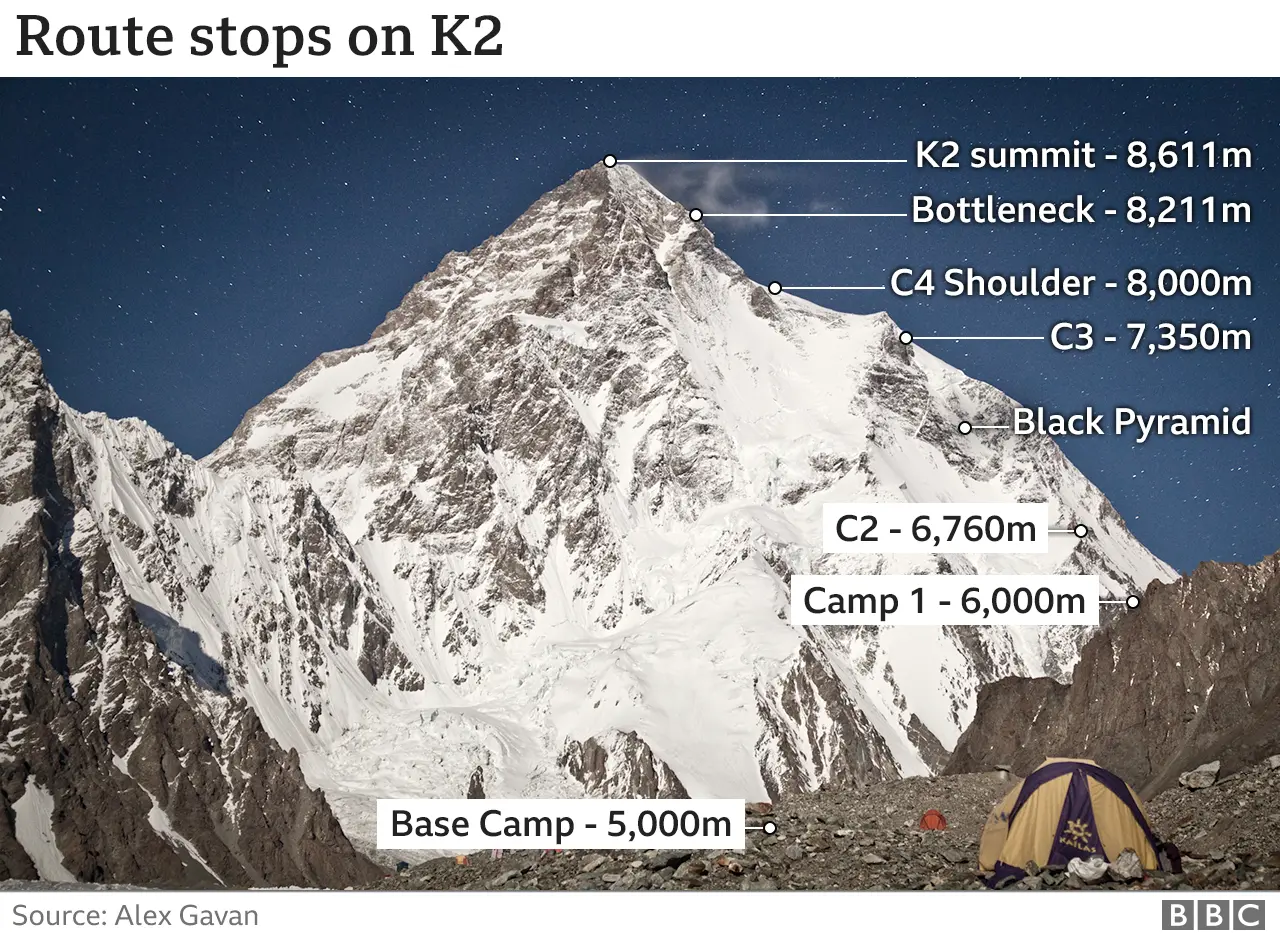

K2 is 8,611m (28,251ft) high - about 200m less than Everest - but is widely considered the most demanding of all in winter.

It is the only mountain above 8,000m - of which there are 14 - yet to be climbed in winter, with or without supplementary oxygen.

"This challenge is even bigger because we're not using supplementary oxygen," asserts Gavan. "Climbing with oxygen is cheating - 8,000m with oxygen is like 3,500m without."

Alex Gavan

Alex GavanFlanked by vast glaciers and thrashed by sub-zero winds, as well as frequent icefalls, avalanches, and rock-falls, a successful winter ascent will require a mix of technical prowess, unbreakable spirit and a measure of luck.

"Sometimes the velocity of the winter jet streams can be 200km/h (125 mph)," says Lunger.

She reached the peak of K2 in the summer of 2014, becoming only the second Italian woman in history to do so without oxygen.

But scaling K2 in the dead of winter when temperatures can fall to below minus 50C will present a far more gruelling task.

"I could be the first woman in history to complete a winter summit," she says of all the world's 8,000m peaks.

If all goes to plan, the pair will reach the summit around mid-February.

Alex Gavan

Alex GavanAs of July 2018, there had been a reported 367 successful climbs of K2 and 86 deaths, which equates to roughly one death in every four. But this harrowing statistic includes all seasons, with or without oxygen.

"This will be the most interesting winter on K2 ever, that is for sure," says mountaineering chronicler Eberhard Jurgalski, who fears there will be too many climbers on K2 this winter, raising the risk of congestion and incidents.

"Even with just a few people, as it's been with the previous seven (winter) attempts, it is dangerous enough. I fear the worst," he told the BBC.

Alex Gavan is well aware of the other expeditions and points out they are sharing "base camp logistics" with another team.

More stories about K2 and the 8,000m mountains

'The right moment'

Tamara Lunger and Alex Gavan are well aware of the perils they face and both have the mountaineering pedigree needed even to consider the task.

Lunger, a former ski mountaineer champion, has climbed two of the world's "8,000ers" while Gavan has scaled seven.

They set off for base camp on Christmas Day and expect to get there around new year. Then the duo will spend about a month acclimatising, and strategically fixing rope lines at various points up their ascent route.

"I have a really good feeling about this expedition," says Gavan. "I feel that this is the right moment, with the right partner to do it."

Legendary Pakistani climber Nazir Sabir told the BBC: "The mountaineering community across the globe are extremely keen on watching the drama on K2 as it remains the last 8,000m peak to allow humans up its treacherous slopes [in winter]."

Dangers of the Bottleneck

In the close-knit community of high-altitude climbing, K2 represents adventure but also provokes a sense of foreboding.

In August 2008, 11 experienced climbers tragically died on K2 after a series of deadly icefalls on an infamously treacherous patch known as the Bottleneck, which needs to be skilfully traversed at 8,200m.

The Bottleneck is well into the territory above 8,000m known in mountaineering as the "death zone", when a lack of oxygen slowly shuts down the human body.

"No matter who you are. No matter your experience. No matter how fit you are. This is simply our biological limit," Gavan says.

"I don't think you can prepare," says Lunger of the Bottleneck. "If you take one wrong step it's a vertical drop of about 3,000m to the crevasse and glacier below."

Alex Gavan

Alex GavanHigh-altitude climbing is a constant dance with death and at one point Lunger decided to confront her fears by visiting the glacier.

She describes a haunting, frozen cemetery of climbers, their clothing and climbing gear: adventurers who lost their lives doing what they loved.

Since that moment she says she feels "at peace" with the risk of what could happen.

During his career, Gavan, who also runs environmental campaigns in his native Romania, has taken part in various search and rescue missions.

In 2018, his Italian friend Simone La Terra was blown away by a gust of wind on Dhaulagiri in Nepal and died aged 36.

"He was like a brother to me," says an emotional Gavan, who helped to recover his friend's body by helicopter. "It was very painful at the beginning, but he was living his potential to the fullest."

"We need to be really wise in choosing the right window for the summit," he adds.

If successful the pair will become stars in the climbing world.

"It's a milestone in high-altitude mountaineering," Gavan says. "I feel like everything in our lives came to this, and now is our chance."