Irish mother and baby homes: Timeline of controversy

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty ImagesThe findings of a major investigation into how women and children were treated in Irish mother and baby homes are due to be published.

The investigation began in 2015 after claims emerged that hundreds of babies were buried in a mass, unmarked grave near a home in Tuam, County Galway.

The "Tuam babies" controversy, as it became known, sparked international shock and outrage.

It prompted the Irish government to set up a wide-ranging investigation into the operation of mother and baby homes, in a bid to shed light on the lives and deaths of thousands of former residents.

The institutions mainly housed women who became pregnant outside marriage, which was widely viewed as shameful and socially unacceptable throughout most of the 20th Century in Ireland.

Ahead of the final report, BBC News NI looks back at the timeline of the Tuam babies scandal.

1925

A former workhouse in Tuam, County Galway, which housed destitute adults and children since the famine era, is converted into a mother and baby home.

It is owned by Galway County Council, but is run by an order of Catholic nuns - the Bon Secours Sisters.

Tuam Home Graveyard Committee

Tuam Home Graveyard CommitteeFor the next 36 years, it houses unmarried mothers and their children during a period when women were ostracised by Irish society and often by their own families if they became pregnant outside marriage.

It was just one of several similar institutions in which about 35,000 single mothers gave birth.

Conditions in Tuam were particularly difficult and research would later show that on average, a child from the home died every two weeks between 1925 and 1961.

1961

Having fallen into a dilapidated state, the Tuam mother and baby home is shut and its remaining residents are transferred to similar homes around the country.

1972

Following demolition of the Tuam home, construction work begins to create a new council-owned housing estate in the area.

PA

PA1975

Two young boys discover skeletal remains in a concrete structure while playing near the site of the former home.

Locals assume it is a famine-era grave and a priest is called to bless the site before the structure is re-sealed.

Following the incident, residents treat the site as an old burial ground, eventually erecting a memorial garden with a Catholic shrine.

2012

After years of research into the history of the Tuam mother and baby home, amateur historian Catherine Corless publishes an article entitled "The Home" in a local history journal.

PA Media

PA MediaShe details the poor living conditions inside the institution and states that a "staggering number of children lost their lives in the home" between 1925 and 1961, mainly due to various diseases.

Ms Corless acknowledges the deaths took place during a period when Ireland had a "very high infant mortality rate" but she questions why there are no records of where the Tuam babies were buried.

September 2013

Ms Corless completes a personal mission to collate the death certificates of 798 children who died at the Tuam home. In all but two cases, she cannot trace their burial records.

Reuters

ReutersFebruary 2014

The Connacht Tribune publishes an interview with Ms Corless about her campaign for a permanent memorial for the Tuam babies, including a plaque displaying all 796 infants' names.

May 2014

The Irish Mail on Sunday publishes a story claiming there are fears up to 800 babies were secretly buried in a "mass grave" at the home in Tuam. This time the story gains international attention.

June 2014

Following weeks of speculation over the fate of the Tuam babies, the Irish government orders a nationwide commission of investigation into Ireland's mother and baby homes.

Announcing the move, the then Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Enda Kenny says babies born to unmarried parents were treated as "an inferior sub-species" for decades in the Republic of Ireland.

January 2015

Mother and Baby Homes Commission of Investigation

Mother and Baby Homes Commission of InvestigationUnder its terms of reference, the commission is tasked with investigating practices in Irish mother and baby homes over a 76-year period, from the foundation of the state in 1922 through to 1998.

The panel is asked to examine the living conditions in the homes as well as mortality rates; general causes of death among residents, burial arrangements and participation in vaccine trials.

They were also tasked with investigating adoption processes in the homes, including whether or not birth mothers were able to give "full, free and informed" consent for their children to be adopted.

October 2016

The commission of investigation begins test excavations at the site of the former mother and baby home in Tuam.

EPA

EPA4 March 2017

The commission confirms that "significant quantities of human remains" have been found during excavations at the site in Tuam and says its is "shocked" by the discovery.

Tests on a small number of remains establish that they were children ranging in age from premature babies to three-year-old toddlers, all of whom died while the mother and baby home was in operation.

The remains were found in a large underground "structure" which was divided into 20 chambers.

The commission says the structure "appears to be related" to the treatment or storage of sewage or waste water but adds it has not yet established if it was ever used for that purpose.

7 March 2017

He says he will await further work from the commission, coroner, and Gardaí (police) before deciding how to proceed.

February 2018

Mari Steed

Mari SteedThe commission appeals to the public for information about the burials of a "large number of children who died while resident" in Bessborough mother and baby home in Cork.

April 2018

Catherine Corless is among those honoured at Ireland's People of the Year Awards - just one of several high-profile honours she receives for her work to uncover the truth about the Tuam burials.

October 2018

Minister for Children Katherine Zappone announces plans for a forensic excavation of the Tuam site, saying the remains of each child will be exhumed, identified and given a "respectful" reburial.

March 2019

The commission outlines its conclusions on burial arrangements at the homes in its fifth interim report.

Its report states that a total of 802 children died inside the Tuam home during its 36 years in operation.

In addition, 12 mothers died while resident at the home, the majority from childbirth complications.

The commission says the human remains it found in 2016/2017 "are not in a sewage tank, but in a second structure with 20 chambers which was built within the decommissioned large sewage tank".

The report says the precise purpose of the chamber structure has still not been established, but it is "likely to be related to the treatment/containment of sewage and/or waste water".

The commission dates this second structure to about 1937 and says: "It seems clear that many of the children who died in the Tuam Home are buried in the chambers described."

It also dismisses theories that the structure may have been purpose-built burial chamber or crypt, saying it "did not provide for the dignified interment of human remains".

The report adds it has not been possible to establish who physically buried the infants but it "seems likely that the burials were conducted on the instructions" of the Bon Secours Sisters.

The nuns' representative had already told the inquiry that the order was "shocked and devastated" by the revelations and apologised "unreservedly" for the failure to provide proper burials.

Separately, the fifth report states that more than 900 children died while resident at Bessborough mother and baby home in Cork, but it is still not known where the vast majority are buried.

Despite "very extensive inquiries and searches", the commission says it has established the burial place of only 64 of these children.

October 2020

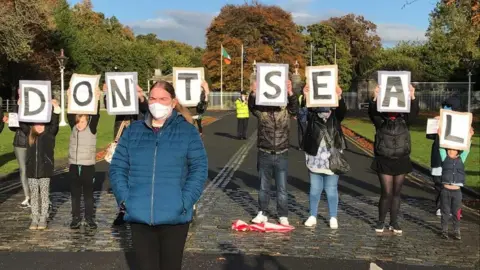

Former residents raise concerns over a new law which they fear could block access to much of the information collected by the commission.

Their campaign warns that many documents could be sealed in national archives for 30 years.

James Ward/PA Wire

James Ward/PA WireHowever, the government insists that "urgent legislation" is required to protect the information from having to be destroyed or redacted when the commission is legally dissolved after its final report.

Minister for Children Roderic O'Gorman explains that the commission has developed databases which could assist family tracing services, but because they contain sensitive personal information, the commission felt obliged to redact "identifying" details from its databases before transfer.

The minister says the new legislation allows a copy of the databases to be given to the child and family agency Tusla to assist family tracing, while the "main archive" can be deposited in line with the 2004 legislation under which the commission was set up.

The bill is fast-tracked through the Dáil (Irish parliament), infuriating former residents.

25 October 2020

Irish President Michael D Higgins signs the bill on mother and baby home records into law.

He notes that the bill raised important concerns "which must be addressed" but he concludes that it does not require referral to the Supreme Court for judgement on its constitutionality.

However, a statement from the president's office says his decision to sign this legislation "leaves it open to any citizen to challenge the provisions of the bill in the future".

10 January 2021

Details of the inquiry's final report is leaked to a newspaper days before publication, angering campaigners and government ministers.

12 January 2021

The publication of the final report of the inquiry into mother and baby homes is described as a "landmark moment for the Irish state".

The government says it will issue an apology over the "appalling level of infant mortality" identified in the report.

The inquiry concludes that about 9,000 children died in the 18 institutions under investigation - about 15% of all the children who lived in the homes.

The commission makes 53 recommendations, including compensation and memorialisation.

An umbrella group representing survivors of Mother and Baby Homes say they have "mixed feelings about the long overdue report".

The Coalition of Mother and Baby Home Survivors says: "This report is fundamentally incomplete as it ignores the larger issue of the forced separation of single mothers and their babies since the foundation of the state as a matter of state policy."

13 January 2021

In response to the final report, the Sisters of Bon Secours offer their "profound apologies" to all the women and children who lived at the Tuam home, their families and to the people of Ireland.

The order admitted its nuns "did not live up to our Christianity when running the home".

"We acknowledge in particular that infants and children who died at the home were buried in a disrespectful and unacceptable way. For all that, we are deeply sorry," the sisters added.

Their spokesman confirmed that the order will take part in a redress scheme.

Later the Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Mícheál Martin issues a formal apology to former residents of mother and baby homes on behalf of the state.

In a statement to the Dáil (Irish parliament), he says a "profound generational wrong" had been visited on women and children who were sent to the institutions.

"We had a completely warped attitude to sexuality and intimacy, and young mothers and their sons and daughters were forced to pay a terrible price for that dysfunction," the taoiseach said.