Dutch police podcast unearths clues to decades-old murder

Netherlands Police

Netherlands PoliceWrapped in an electric blanket metres from a busy highway in the Netherlands lay the body of a man in such a state of decomposition he was impossible to identify.

It was August 1991 and the man's chest bore several stab wounds. The local workers who found him told police it was the stench that led them to his corpse.

The discovery marked the beginning of a decades-long mystery in the Netherlands, with police unable to identify the victim, much less find the person responsible.

But the truth could now finally be in sight after Dutch police launched their first-ever podcast aimed at solving a crime.

True crime podcasts are nothing new, but for police in the Netherlands this was an unprecedented venture. Thousands tuned in to the three-part series when it aired last month and tip-offs have been coming in ever since.

It began with the body in the blanket

When police arrived at the scene, they searched the corpse for any trace of the man's identity.

There was no ID and decomposition had rendered his body unrecognisable.

Johan Baas had recently been appointed as a detective in the city of Naarden when the body was found. "I was on vacation leave for a few days when my boss called me and informed me about the discovery of the body," he recalled.

"It was my first major case, so the choice was clear. I went straight to the crime scene."

Mr Baas remembers it vividly. "The body was minutely dissected and everything was recorded photographically and in writing," he said.

During the 1990s, Dutch police estimate that about 90% of all murders were solved. But DNA technology was still in its infancy and resources were limited, so the case was harder to crack than it might be today.

Large amounts of blood or sperm were needed to find an offender and there was no DNA database.

"We had to make do with existing means such as fingerprints, but the victim's prints did not appear in the Dutch database and we did not progress further internationally," said the detective.

Looking for clues

No witnesses came forward and police had no picture to hand out because of the condition of the corpse.

Efforts to analyse his clothes bore no results and the electric blanket, produced in Germany in the 1960s, was sold by the thousands in the Netherlands, Belgium and France.

Any hope of solving the crime hinged on a gold ring found on one of the victim's fingers.

Netherlands Police

Netherlands PoliceDetectives discovered that it was bought through a mail order company called Otto and began tracking down the buyers.

Most still had the ring in their possession but one man said he did not have it anymore because he had sold it to a man at a bar in Amsterdam.

Witnesses confirmed the sale and said the buyer went to the same bar almost every day.

However, the mysterious character, believed to be Turkish, had not been seen in weeks and police never discovered who he was or if it was his body that had been found.

In Johan Baas's later investigations it was always clear who was the victim and who was the perpetrator. But police had hit a stumbling block and the case was ultimately dropped.

How the podcast began

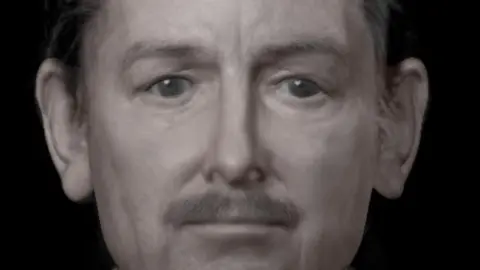

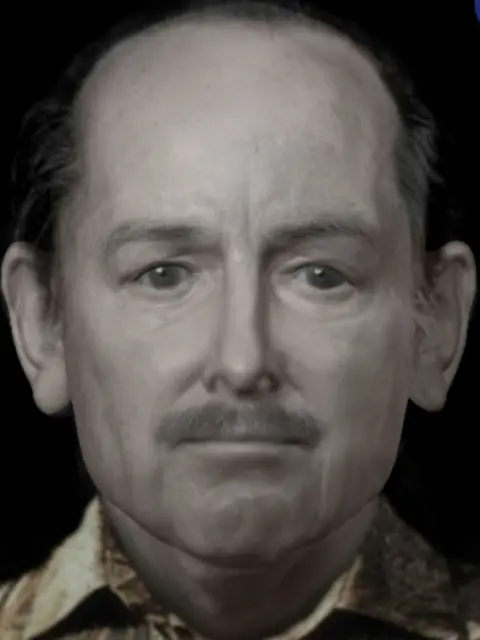

Police reopened the case a couple of years ago, using new technology to analyse the body and carry out a facial reconstruction of the victim.

They discovered that the man would have been around 65 years old in 1991 and came from Eastern Europe.

Netherlands Police

Netherlands Police

Unable to crack the case alone, last month they opened the case to the public for the first time, with a podcast (in Dutch).

Listeners across the Netherlands tuned in and came forward each day with information that may be relevant to the case.

Police said they could not give details of the tip-offs they had received but several had contained useful information.

"Our first goal is to identify the victim and tell his relatives after 28 years what happened," said Rob Boon, coordinator of the police Cold Case team who led the podcast.

"Our second goal is to find the killer and bring him or her to court."

Can podcasts work?

Criminologist David Wilson said it was natural for Dutch police to want to capitalise on the popularity of true crime podcasts and pass on details of crimes and unsolved cases.

"True crime is incredibly popular and the police are as aware of this as any other individual, group or industry," he said.

But police podcasts have their limitations, as there are some areas they cannot touch, because of laws on what they can say so as not to prejudice any future case.

"The podcaster can suggest things that the police might not be able to suggest. They can raise possibilities that the police wouldn't be able to raise," he added.

Even so, numerous cases have been solved by police crime appeal programmes such as the UK's Crimewatch and its Dutch TV equivalent, and Mr Wilson is confident podcasting will probably bring the same results.

Johan Baas is no longer on the case but the detective sent to the crime scene in 1991 believes there is a chance the victim can be identified.

No names have emerged so far and Mr Baas says the man's family need to know.

"I know what impact a loss has on those left behind. Of course you want to arrest a suspect as a detective, but unfortunately it never came to that."

You might also like: True crime podcast helps woman find her brother's grave