Greek election: Why frustrated young voters are turning conservative

BBC

BBCLike many young Greeks, Tasos Stavridis plans to leave the country once he finishes his degree in political science.

"Our financial crisis has gone on much longer than we expected and we are so exhausted," says the 22-year-old.

His generation has been severely impacted by the country's decade-long financial crisis.

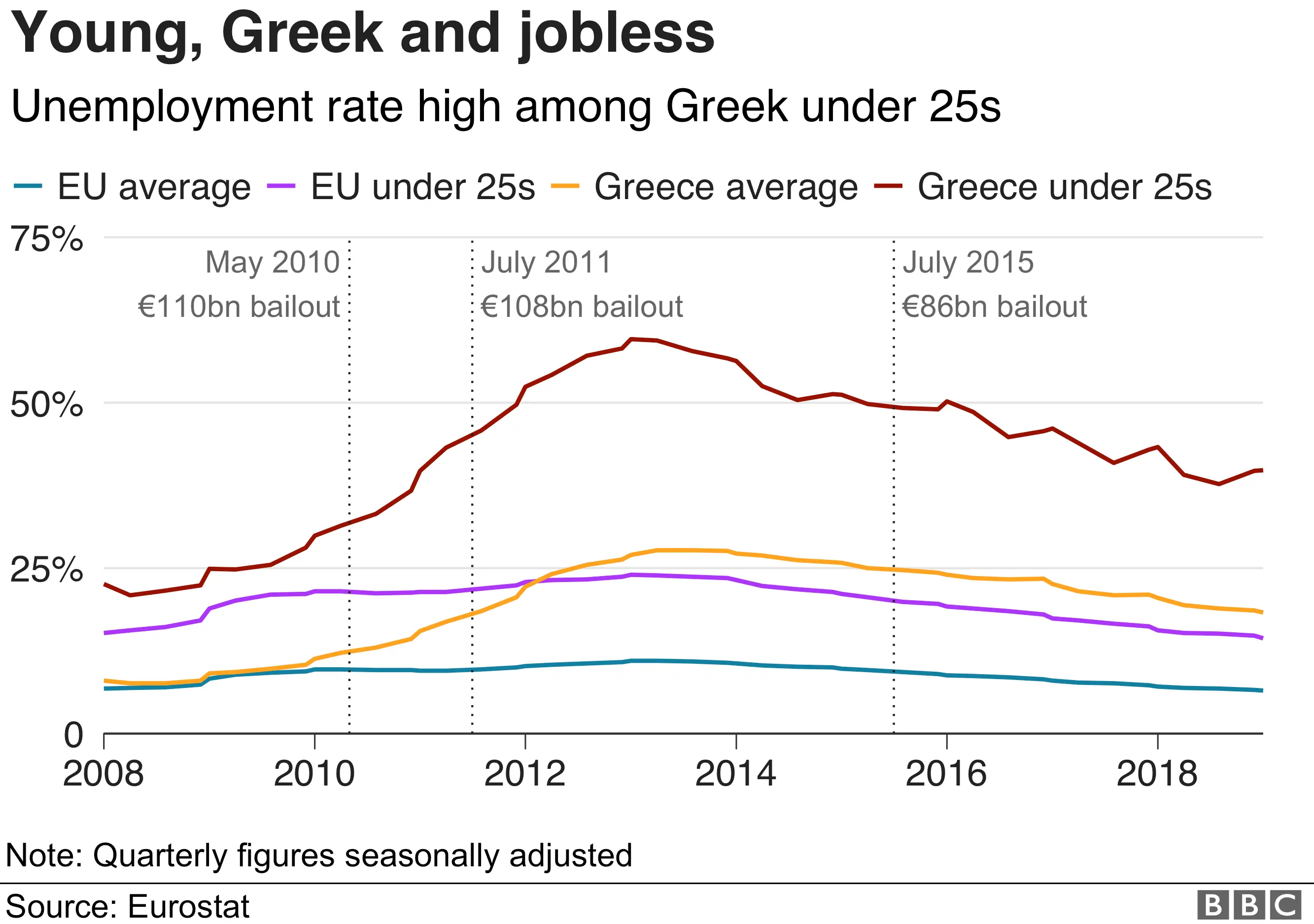

With a youth unemployment rate of almost 40%, between 350,000 and 400,000 graduates have emigrated since 2010.

"Most of my friends plan to leave too. In Greece the salaries are so low, and the economic situation is so bad," Mr Stavridis complains.

As Greeks prepare for a general election on 7 July, he and his peers are not backing a radical, youth-orientated party, such as the current-ruling Syriza which swept to victory in 2015.

In last month's European elections, the highest percentage of 18- to 24-year-old voters (30.5%) backed New Democracy (ND), the traditional centre-right party widely considered partly responsible for the very crisis that still impacts them.

What is the centre right offering?

ND leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis, who is widely expected to win the general election, is promising lower taxes, greater privatisation of public services and to renegotiate a deal with Greece's creditors that would allow more money to be reinvested back into the country.

"The truth is, I blame them [for the crisis] too," admits Mr Stavridis. "But I believe Mitsotakis has made a lot of changes. I agree with the economic plan this party has, and I believe it will help us escape this situation."

"We must focus on the private sector in order to get better economically," he believes. "Our public sector is inefficient and lazy."

Greece has long been associated with radical youth politics, from the student uprising that helped bring down the military dictatorship in the 1970s to the anarchist riots that accompanied the debt crisis.

Are young people losing their radicalism?

From talking to some young Greeks, it seems that cynicism has emerged from years of revolutionary rhetoric accompanied with no visible change in circumstance.

"The last time my family supported something left, it turned out to be a lot worse," says Zoe Babaolou, a 19 year old from Thessaloniki who voted for New Democracy in the European elections. "It seems better to return to something safer."

Syriza rose to power on a strong anti-establishment platform but disappointed many of its supporters after ignoring the results of a referendum on the eurozone's austerity package.

Ms Babaolou, whose father lost his job at the start of the crisis, says her parents felt "very disappointed and betrayed" after backing the party.

Timeline: Greece's financial and political crisis

- 2009: A year after the financial crisis hits, the Greek budget deficit is revealed as more than 12% of the entire economy (GDP) - the true figure is later revealed as 15.4% of GDP

- 2010-11: Teetering towards bankruptcy, the government gets two bailouts from the EU, ECB and IMF totalling €240bn

- 2013-14: Youth unemployment peaks at almost 60% and the government collapses

- Jan 2015: Syriza party takes power under anti-bailout PM Alexis Tsipras, after the election defeat of the ruling New Democracy

- June-July 2015: Banks shut as talks with creditors fail and the government rejects EU/IMF bailout conditions. Greeks back Syriza in a referendum to turn down the bailout

- August-Sept 2015: Tsipras eventually agrees a third bailout of €86bn and imposes tough, new austerity measures. Despite the deal he is re-elected.

Although New Democracy is economically liberal, its social stance is solidly conservative.

Its politicians preach a focus on "family, Church and nation" and Mr Mitsotakis has made appeals to the far-right with a promise to crack down on immigration.

In comparison, Syriza has brought in pro-LGBT laws and worked to separate Church and state.

What is the youth appeal of the centre right?

Given that most research shows young Greeks are more socially liberal than older generations, why are they backing ND?

"I'm not proud of their social policies to be honest, but I truly believe that if we make an effort to improve the economy then social liberalism will be easier to implement in future," says Tasos Stavridis.

Zoe Babaolou adds: "We voted for the ideology in 2015 and we didn't see any changes. So I'm more interested in the economic measures."

This sense of cynicism is obvious when talking to young Greeks. Outside a coffee shop in the leafy Athens suburb of Kifisia, 19-year-old Giannis Reklos says he is voting New Democracy because "they are the best out of the worst".

"I'm not in favour of Syriza, and any smaller party will just get around 1% of the vote and not be able to do anything," he adds.

However, he says he and his friends still have reservations about backing the party due to the fact that leader Mr Mitsotakis comes from one of Greece's most established political dynasties.

That is a sticking point in a country where corruption and lack of meritocracy are named by graduates as two of the main reasons for emigrating. "It's a big problem for Greece," he admits.

Zoe Babaolou says the overall mood among her friends is of a lack of interest, rather than hope.

"I see many people having no idea what to vote or what they're leaning towards," she says. "They see their families being destroyed economically… and they feel that nothing is going to change."